“Ruta de los Parques” Positions Chile as a Global Leader in Sustainable Tourism

Can tourism be community-inclusive, ecologically-sensitive, and economically advantageous? Chile consolidates 17 National Parks in an unprecedented commitment to conservation.

The ex-Chilean president Michelle Bachelet’s announcement of an unprecedented national conservation accord in March of 2018 marked a departure from several decades of assiduous federal promotion of extractive industry in favor of tourism.

Ruta de los Parques is a conduit to rugged adventure and diverse ecosystems.

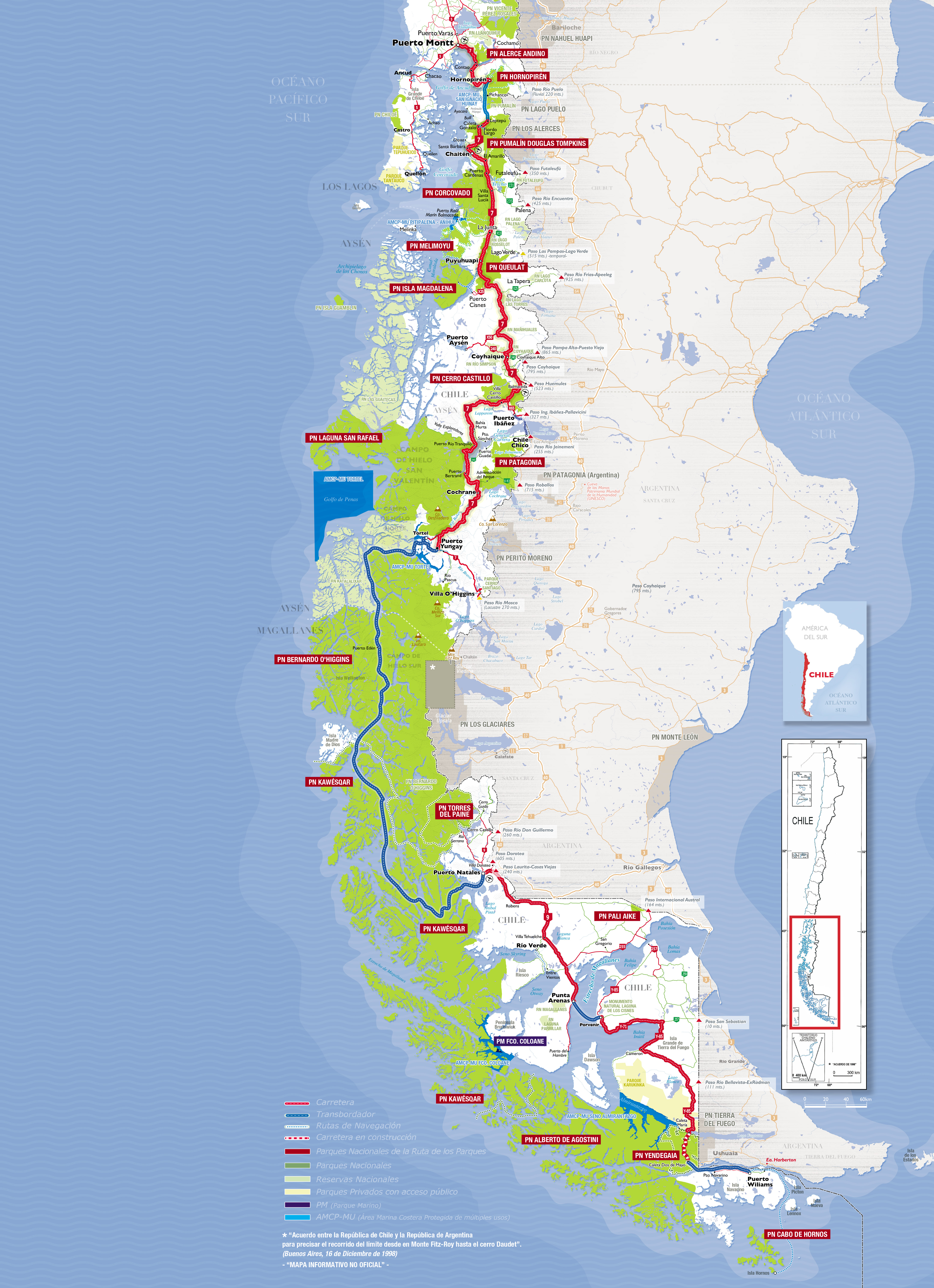

Galvanized by the million-acre donation of private Parque Pumalín by American conservationist group the Tompkins Foundation, Bachelet pledged 9 million acres of new national parkland and created the framework for a consolidation of 17 total parks scattered along Chile’s ample latitude. The 1,500-mile link-up, officially established in September, is called La Ruta de los Parques, or Route of the Parks. It repurposes portions of the Carretera Coastal (Southern Highway), originally eked out of the landscape by 10,000 soldiers under the despotic command of dictator Augusto Pinochet in the 1970s.

Ruta de los Parques is a conduit to rugged adventure and diverse ecosystems. The well-known Patagonia and Torres del Paine National Parks headline the nascent assemblage, but each park contributes its unique character to the distinctly Chilean experience. Foreign travelers will experience a dizzyingly diverse display of natural sensoria including glaciers, volcanoes, temperate rainforests, and turquoise rivers. Penguins percolate the coastal fjords of Pumalín National Park. The 7,500-foot Corcovado Volcano rakes the atmosphere above its namesake parkland. With pastel panache, flamingos patrol the craters that punctuate the lunar-esque lava fields of Pali Aike.

“This is an invitation to imagine other forms to use our land. To use natural resources in a way that does not destroy them. To have sustainable development - the only profitable economic development in the long term,” Bachelet announced in a speech.

“Local communities are the texture and context for Ruta de los Parques,”

Environmentalists laud her vision of developing Chile through responsible tourism rather than extractive industry. As part of La Ruta’s establishment, the Chilean government will partner with the Tompkins Foundation for 10 years to oversee the project. The Tompkins Foundation is an activist conservancy headed by Kris Tompkins, wife of the late North Face founder Doug Tompkins. They’ve invested millions of dollars to protect and preserve land in Chile and Argentina since the 1990s and will play a salient role in La Ruta’s management.

“Local communities are the texture and context for Ruta de los Parques,” Kris Tompkins stated. Her words indicate that community-informed management and local economic growth are fulcrums of the mission. But not everyone is convinced; last year, local ranchers occupied one of the Tompkins Foundation’s parks to agitate for what they perceived as a barrier to productive land development by foreign conservationists. Moreover, many of the parks currently lack the infrastructure to handle a significant incursion of visitors. According to the official website, the Route of the Parks encompasses more than 2,800 kms, 24 distinct ecosystems, and 60 human communities. Management is a daunting task, given La Ruta’s latitudinal largess and limited budget. How will Chile obviate the problems of over-visitation and environmental degradation that have plagued, for example, popular mountaineering destinations in India, among many others? The striking scenery leaves little room to doubt the allure of La Ruta, but plenty to wonder about tourism’s potential impact on local communities and ecosystems.

“When the park explodes with visitors, we don’t have the time, resources, or money,”

Park ranger Juan Toro Qurilif of Torres del Paine National Park expressed his concerns about over-visitation. “When the park explodes with visitors, we don’t have the time, resources, or money,”. Torres del Paine, which sees 250,000 visitors every year, has a limited annual budget of $2.1 million and only 30 full-time park rangers. He’s not alone in budget concerns; Chile’s National Forestry Corporation (CONAF) manager Richard Torres Pinilla stressed the necessity of federal, regional, and international funding to provide the infrastructure and labor to manage tourism. Even in the U.S., officials are struggling to keep up with recent surges in visitation. Over-crowding has resulted in littering, traffic congestion, and an $11 billion backlog of upgrades. Granted, Chile’s isolated Parks see just a fraction of the crowds that descend upon Yellowstone or Grand Canyon, but they also lack the paved roads and other infrastructure in place at the U.S. locales.

CONAF and the Tompkins Conservation will meet the challenges head-on. “Nothing will be developed without a long-term vision,” executive director of Tompkins Conservation Chile Carolina Morgado assures. Four years ago, the foundation took to the countryside to survey local attitudes towards a possible link-up route. “We received a very positive response from local communities,” Morgado reported. “People were proud to think of themselves being leaders in protected areas.” The Tompkins Conservation also commissioned a feasibility study which suggested that the expanded park system could generate $270 million annually and employ 43,000 Chileans. In the U.S., conservation interests are often at odds with local development agendas. But according to Morgado, Chileans almost universally embrace their protected lands. “Our National Parks have never been seen as an upset to the economy—rather, they contribute to Chile’s world image as a conservation destination,” she says.

“We will learn from Pumalín’s world-class infrastructure as a model for La Ruta’s other parks,”

To prepare the parks for an uptick in traffic, Chile will employ the Project Finance for Permanence (PFP), a long-term funding stratagem that has seen success in Costa Rica, British Colombia’s Great Bear Rainforest, and Brazil’s Amazon. PFP repurposes methods of private sector project financing for use in large-scale conservation projects. For example, the approach mobilizes all stakeholders (funders, NGOs, governments) simultaneously under a protection plan that stresses permanence. Enduring ecosystem health, sufficient long-term funding, proactive governance, and sincere community buy-in are crucial to a permanent conservation plan. Permanent protection of La Ruta’s parklands will necessitate substantial expenses for initial consolidation and ongoing funding for infrastructure projects like visitor centers and campgrounds. Project Finance for Permanence relies on government participants to secure public support, NGOs to tap their funder base, and lead foundations to accrue private philanthropy. The strata of stakeholders coalesce in a single all-or-nothing deal to ensure commitment by all parties to protection in perpetuity.

Ideally, Project Finance for Permanence will nourish the altricial Ruta with the necessary funds for development. Morgado says that the panoply of parks will look to Pumalín National Park as the apotheosis of responsible stewardship and sustainable infrastructure. Doug and Kris Tompkins labored for decades to piece together Pumalín, a million-acre swath of waterfall-laden forest. The Tompkins’ fastidiousness is evident in the hand-crafted park facilities, successful wildlife-rehabilitation programs, and established trail systems. “We will learn from Pumalín’s world-class infrastructure as a model for La Ruta’s other parks,” Morgado says.

La Ruta de los Parques promises a 28-million-acre taste of the tantalizing cultural and biotic endemism of the National Parks that speckle southern Chile. National Parks are participatory and enduring, making them arguably the highest form of ecosystem protection. They are the property of every Chilean; accordingly, conservation must operate under obligation to culture and community. Chile has emerged on the global stage as a preeminent champion of National Parks as a vehicle for tourism and sustainable development. La Ruta is a large-scale experiment in profitable conservation; the stakes are high, and Chile stands to reify its international image of a conservation leader. Should National Park tourism prove both economically advantageous and ecologically sound, Chile’s vision of profitable protection may inspire efforts to create new National Parks in the U.S. and internationally.

Cover photo: Guanaco at Patagonia NP. Provided by Tompkins Conservation.

Comments ()