Alexandra David-Néel: The 19th Century Parisian Anarchist who Explored Tibet

Disguised as a beggar to avoid betrayal, and walking more than 2,000 km in the fierce Himalayan winter, the French orientalist eventually reached the forbidden capital Lhasa on February 23rd, 1924.

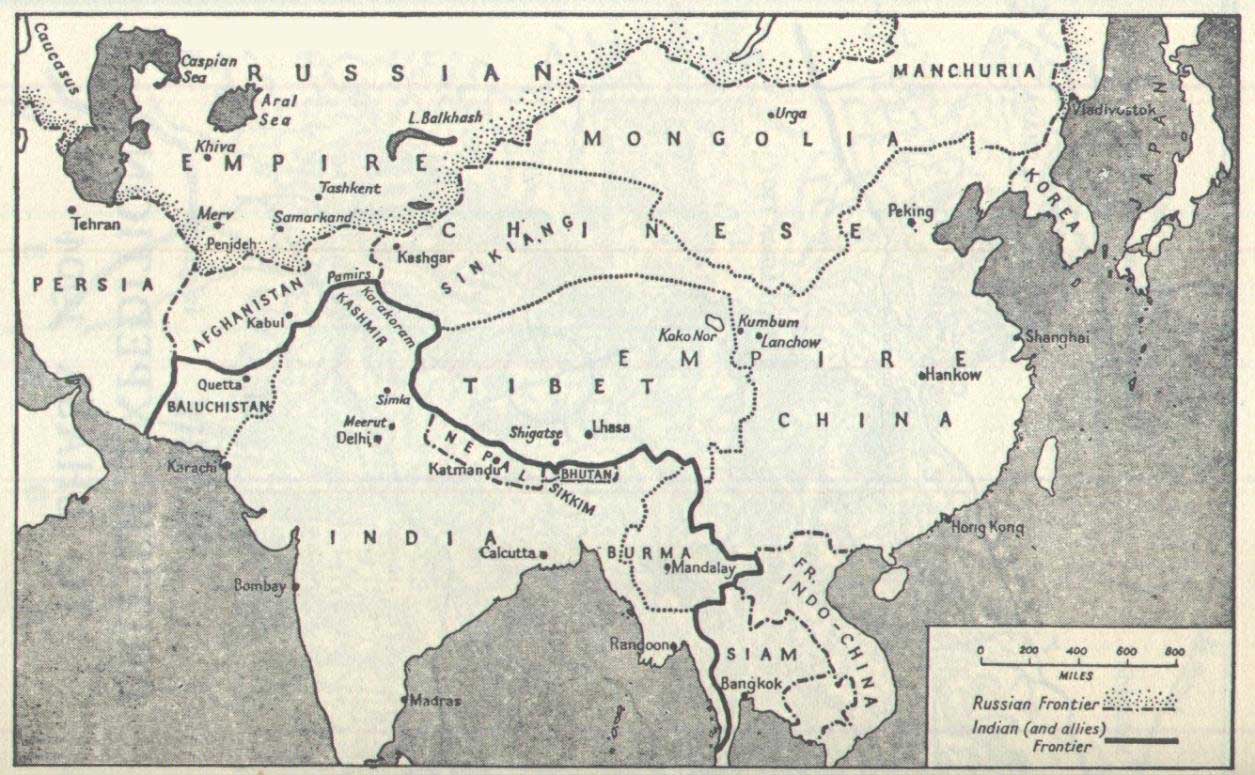

We are used to considering the word exploration as something from the far past. We instinctively imagine camels roaming the Silk Road, caravels sailing towards unknown continents. But many places on the globe have actually been discovered and mapped only recently. This is the case of Tibet, the Himalayan kingdom where foreigners had been denied access for a long time.

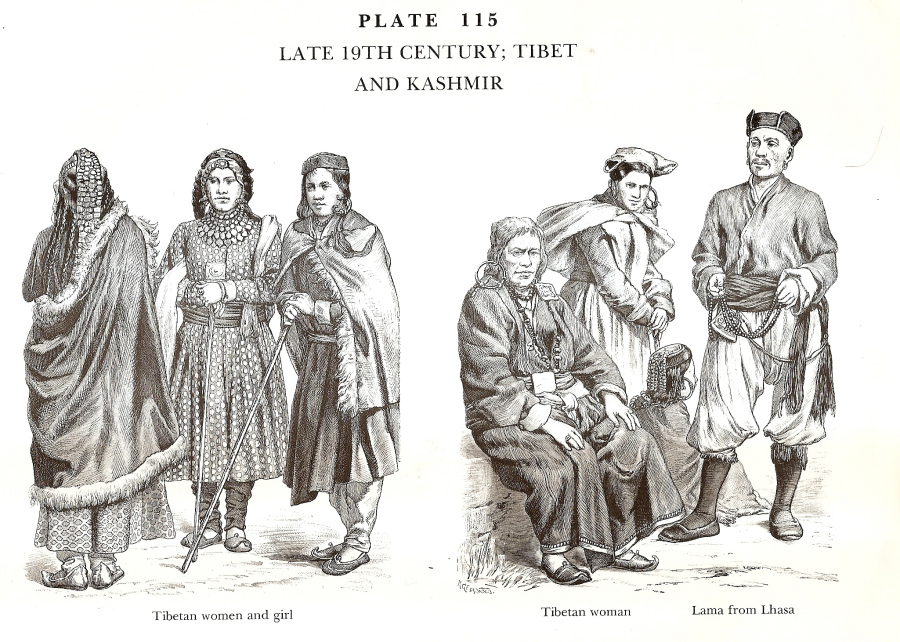

Explorers are often geographers, sailors or geologists. She was an orientalist, specialist of Tibet, opera singer, journalist and anarchist, Buddhist and French. Born in 1868, Alexandra David-Néel developed a consuming passion for Asia and Tibet while studying old manuscripts at the Asian Arts National Guimet Museum in Paris. She remembers in her book L’Inde où j’ai vécu (“The India where I lived”): “At that time, the Guimet Museum was a temple. (...) In the little room, quiet calls rise from the pages that are flipped through. India, China, Japan, all the points of this world that begin beyond Suez appeal to the readers… vocations born… mine was born here “. After her wedding with Philippe Néel, manager of the French railways in Tunisia, she continued to be consumed by the need to see the world and left Tunis where the couple lived, for India. Promising her husband that she would return within eighteen months... her journey around Asia actually lasted fourteen years. From Ceylon to India, Japan and Singapore, she became the first Western woman to meet with the Dalai-Lama, roaming the ways of China and Korea, living in a cave at 12,000 feet for two years in Sikkim as an anchorite. Alexandra David-Néel not only walked through places, she experienced them, studying religions and cultures of the locals she met. Lo-pa of Tibet, Gologs of the Qinghai, monks of all the cults of Buddhism had no secrets for the lady who spoke Tibetan, Sanskrit and partly mastered Chinese.

This knowledge about local habits and customs was a determining point for her journey to Lhasa. In those days indeed, the Tibetan territory was in the hands of the United Kingdom and forbidden to foreigners. No Westerner had succeeded in this incredible quest. Not only were the weather conditions hostile, but the land was practically unknown, with no roads or railways. It was also dangerous and plagued with gangs of robbers, many missionaries had already been killed. Travellers as the French Jules-Léon Dutreuil de Rhins and Fernand Grenard, the Irish army officer Deasy or the Swedish Sven Hedin: all failed or died on their way to the city of the Potala. Alexandra David-Néel was not ready to fail.

From the city of Tsedjrong (currently Cizhong in Yunnan), they followed the course of Salouen and Po Tsangpo unmapped rivers, and sometimes crossed them on ropes made of straw that served as footbridges. One day, the rope almost snapped and the explorer had to wait, hung above the icy waters, to be rescued by a local. Often, the mother and her son walked during the night to avoid being noticed and questioned by curious locals, and eventually would get lost. One night the two pilgrims researched for the right way, they faced a violent snow storm and could not see enough to find a shelter. Sleeping at the open air for several days, they fed themselves with melted snow and leather pieces from their boots. Aphur Yongden sprained his ankle because of his extreme state of weakness and the two only survived thanks to their mental strength and determination. Snow burns, forced fasts, fevers due to the extreme temperatures and walks of several days without any sleep to cross passes at more than 5,000 meters, the two supposed-pilgrims put their bodies to a severe test. But one of their greatest fear was to be identified as filings (foreigners in Tibetan). David-Néel almost got caught several times when eating with her fingers, erasing the dye on her skin. But however tiresome this walk might have been, the woman declared in My Journey to Lhasa: “this picturesque life, I consider it the most delightful one can dream of, and I regard it as the happiest days of my life when, with my miserable bundle on my back, I was wandering the wonderful Land of the Snows up hill and down dale “.

Indifferent to the fame and the praise testified by the international press after her feat, she headed back for another nine-year journey to the continent where she felt she really belonged at the age of sixty-nine years old. “I am a savage my dear - she wrote to her husband - I only like my tent, my horses and the desert “. Today, one can dive into Alexandra David-Néel’s lively books in which the adventurer conveys the authentic flavor of Tibet as she observed it, described with affectionate humor. The house she lived in until the age of 100 in Digne-les-Bains is now a museum that presents keepsakes of Alexandra’s journeys: box cameras, a Tibetan rosary made of 108 pieces of human skulls, her automatic pistol and a cooking pot. Her life, her determination and physical fortitude is still an inspiration for many travellers and photographers, and her tales of adventure and vivid description of Tibet will continue to delight generations of readers.

Comments ()