In Pursuit of Answers in the Himalaya

Why I abandoned a top-notch Ph.D. program for thru-hiking in Nepal to reengineer myself and set a new personal trajectory.

In 2018, I quit my prestigious Ph.D. program to look for adventures and a different way to be a scholar. In pursuit of answers on what to do next, I joined the Himalayan Practicum, a trekking expedition with an in-built executive education program. In the Himalayas, I was hoping to find ‘my Antarctic’ and a challenge at the brink of my abilities. Somehow, I found both less and more than that. My journey began a world away in Boston.

West of downtown Boston lies the city upon the hill, a studied dream of white stone and Collegiate Gothic. The Heights, Boston College’s main campus is both majestic and cozy, gaining in serenity what it loses to campuses of Harvard or MIT in renown. Boston College was originally meant to educate the Irish diaspora, and Celtic aesthetic is still everywhere, echoing from arched doorways and stained glass windows. Now it is a global research university. In the Fall of 2017, I was a Ph.D. student in one of the world’s top programs of International Higher Education, my field.

I was sitting comfortably in the graduate students’ lounge when I got a call from Andrei Volkov. Volkov is the President of the Russian Mountaineering Federation and also the leader of the university transformation group, of which I am also a part. We had a concrete work-related agenda for our conversation, but he really wanted to talk about the Himalayan Practicum he had just returned from, in the Dhaulagiri area of Nepal.

Volkov’s Himalayan Practicum is a manticore with the body of a trekking expedition, the head of executive education, and the sting of career-oriented design thinking. In practice, you have a group of hand-picked top managers moving fast and light at high altitude by day, and engaging in intense seminars at night. Volkov selects unique offbeat routes, works with a team of skilled mountain guides from the Alpine Academy (a spinoff of the Russian Mountaineering Federation) to make the experience seamless, and moderates the discussions himself.

Want to live deliberately? Forgo civilization for a while.

The very idea, of course, is not new and conceptually stands on the massif of philosophies from Aristotle to Thoreau, and practical wisdom. Want an upgrade? Remove yourself from everyday situations. Want to live deliberately? Forgo civilization for a while. Some colleges, like Deep Springs with its remote cattle-ranch campus, or Thoreau College with the Humans & Nature core seminar, incorporate the outdoors directly into their curricula. Business schools are particularly keen on expedition education. Strategic planning, adjusting to a group of people you cannot escape and soldiering on despite discomfort are obviously requisites for executives. These might be fastest to acquire during intense outdoor ventures. Columbia Business School and Johns Hopkins Carey Business School exercise different leadership frameworks by appointing a daily leader; Cass Business School (City, University of London) aims to form an ‘explorer mindset’. Explorers have a craving for the beyond; they must be good at problem-solving and open to new learning.

Most programs at Moscow School of Management SKOLKOVO where both Volkov and I work have a physical component -- anything from diving to running the distance of the equator in a team. Some include an ‘extreme module’ which takes students to Kamchatka or the Crimean Peninsula. In Kamchatka, students from the MBA program get to ride snowmobiles, go inside a volcano on a helicopter, ascend the Vilyuchinsky pass, set up camp, spend the night in the snow and then reflect upon the experience and their lives beyond it. The School’s obsession with athleticism is a modern reincarnation of an ancient idea: you must train your body to train your character, and you must train your character to train your mind. The ‘extreme’ component is Volkov’s personal imprint.

The Himalayan Practicum is the Kamchatka module on steroids: it is longer; you get not one, but daily discussions; you are farther removed from civilization. Yet, in a way, it is a continuation, as the majority of Practicum participants are former MBA students.

“A genuine higher education is none other than a transformation of being.’”

There is a touch of rebellion to Volkov’s endeavors. He belongs to a minority group of educators waging a war against education becoming harmless. Ron Barnett, a philosopher of higher education, in his Will to Learn, wrote that ‘a genuine higher education is none other than a transformation of being’, and as such it is complex, tough, and potentially dangerous. True learning, just like true teaching, is the ultimate danger.

‘I got so lucky!’ In 2017, Volkov was particularly content with how things turned out. He spoke of Inna Yun, a girl with a background in philosophy who enriched the evening seminars immensely. ‘So difficult… And so beautiful!’, he added, recalling trekking to the Hidden Valley, a bare area between 5000m passes. I could almost picture it: graphic landscapes, painfully sharp discussions, fire flickering in the girl’s eyes while she talked. Dust, laughter and adventures!

Volkov finished talking about the Practicum and cheerfully inquired about me. Me? I was looking at the Heights through the window. The world was bathed in golden autumnal sunshine. I was living my New England dream. And in the dream, I was bored.

Even if you have never applied to a Ph.D. program at an American institution, you might have heard that the process is long and exhausting. When your applications are finally in, you come out empty, like a runner after finishing a marathon for the first time. They keep you in the air for months as you wait for the decision. Falling in love or even making friends is inadvisable as you will have to abandon them, moving across the country, or even across the world. I have a deep respect for the system because you must be resolutely determined to go through all of these trials. And I really was. I did not mind the application process or the Ph.D. program itself being difficult, as long as it offered me the transformation I needed.

I left the graduate lounge and wandered around the campus. No amount of Gothic architecture could cure the feeling that I was in the wrong place. The Ph.D. was not transforming me, it was slowing me down. I was very jealous of the participants of the Himalayan Practicum. But this was only a part of the problem. There was no risk in my education. No flair.

We are so far from where we started. The research seminars of yore presupposed acute disputes among students fighting with their charismas, enforced differentiation of academic personalities, passionately pursuing novelty. I might be deluding myself. Maybe, we have never really created an institutional form of fostering passion. Maybe it has only appeared sporadically, as a wonderful mutation. Where I was, discussions were comfortable and polite. Everything was safe, yet stagnant.

If there was even a flicker of flair, I was going to follow it. I did not know where I had to go, but I knew I had to leave. Abandoning plans is not easy, and I was in for several painful months of the should-I-stay-or-should-I-go conundrum. I made a deal with myself: if I did end up leaving the Heights, I would, among other things, take part in the Practicum’18 in the Kanchenjunga area to figure out how to restructure my goals. In winter, I was already shopping Patagonia for a fleece sweater from the required list of clothing and equipment. In May, Boston College and I went our separate ways, parting on good terms.

Normally, the build-up to the Practicum includes a personal essay, individual and group training, and a meeting or two to discuss the format. For individual preparation, the participants mostly run. The most eager or anxious might go on a small trekking trip with full gear. Physical preparation consisted of indoor climbing classes, for which I developed a quick and firm aversion, finding the experience claustrophobic and asphyxiating.

For the Practicum’18, Volkov, Konstantin Dikovsky (our colleague in SKOLKOVO ventures, a photographer, and a mountain guide), and I expanded the intellectual part of our preparation. I asked them how long it normally took the participants to get used to the format of evening discussions, and they replied that it was about five days. Hence, to spend less time on the adjustment during the actual trekking we would have five meetings: ‘Human Limits’, ‘The Team’, ‘Managing Growth’, ‘Buddhist Philosophy’, and ‘How to Do a Presentation’. The last meeting concerned personal presentations during the Practicum -- here is career-oriented design thinking for you. The meetings were complemented with a reading list which featured titles like Idealized Design by Russel Ackoff, Into Thin Air by Jon Krakaurer, Touching the Void by Joe Simpson, and “The White Darkness”, by David Grann, The New Yorker’s long read about Henry Worsley, an explorer who attempted a solo unaided crossing of the Antarctic.

“Everyone has an Antarctic...something difficult, lying at the brink of your abilities, that you must reach, conquer, or create.”

While Volkov and Konstantin were working to maximize the level of participants’ preparedness, I was getting high on a new and exhilarating genre, adventure memoirs. In “The White Darkness”, Grann quotes Thomas Pynchon: ‘Everyone has an Antarctic’. The Antarctic is something difficult, lying at the brink of your abilities, that you must reach, conquer, or create. It is also something that gives you the necessary answers about yourself. A year later my friend and I were in a forest café, and she said pensively, ‘I think an Antarctic is not enough. It is something tangible, something that is out there in the real world. You also need an Atlantis’.

She defined an Antarctic as the goal drawing you to itself, compelling you to act. You have a profound understanding that it is something you cannot not do. The workings of the human psyche imply that you will constantly lose faith in your success, and sometimes even question the goal. An Atlantis is a more metaphysical and less rational entity. It is will, aspiration, the part of your identity and journey where there are no doubts. The two are inextricably linked.

On top of the books from the list, I was also reading Ellen McArthur, Sabrina Little, Stephanie Case, and Lizzy Hawker, apparently building a new canon of favorite texts. At the core of our engagement with literature is the conversation between a reader and an author; the books we read reflect the company we like to keep. Books on mountaineering were captivating, but Hawker’s Runner was a game changer. She wrote about running: ‘It gives me a moment where I almost touch reality. A moment where everything seems to make sense. A moment where I think I understand.’ Her words called out to something I had thought about before and could not express. They called out to a moment when I lose myself to the dialogue with the world I run through. I quoted Runner over and over, ad infinitum and ad nauseum.

I started running in 2016. That year, my world exploded.

I started running in 2016. That year, my world exploded. Running showed how impossible could be turned into manageable. I loved it at once, unconditionally and completely: hard weeks, tapers, solo runs, group runs, when it hurts and when it doesn’t anymore. It was like adding a new dimension to my life. It also planted insatiable hunger for realizing new horizons inside me.

In my life, it seems like everyone is burning with the same yearning. I am surrounded by people who seek adventures instead of eschewing them. Outside my bubble, adventurers make a small fraction of the population, no more than 1%. Which is still a lot. Keith Johnstone, a playwright and an educator, and himself a fierce opponent of playing safe, mused: ‘Your parents had no idea… They would just spend time on the beach. You keep going up and down the cliffs!’. He was commenting on Free Solo and capturing the growing fashion of going higher, deeper, farther, and longer. Of going into the woods instead of staying home.

In 2018, 50,773 runners registered for the New York Marathon, and 2,472 triathletes participated in the Hawaiian Ironman. In 2019, 2,543 ultrarunners took part in UTMB, Ultra-Trail du Mont-Blanc, the 170 km single-stage mountain ultramarathon. The number of ultramarathons has risen 1000-fold over the last 10 years. The diving industry is growing rapidly. Even ice swimming is gaining popularity! All of this has been done mostly by amateurs who chase the cardinal category change, from mundane to epic for their lives.

On the trail, we would all become trekkers, stripped of our social status down to gear and sore muscles.

In the spring of 2018, I took part in the Becca Pizzi 5K road race in Belmont, Massachusetts. Becca Pizzi has won the World Marathon Challenge, 7 marathons on 7 continents in 7 days, twice. In her TEDx talk at Waltham she asks, with a perfect combination of humility and confidence: ‘So, I thought… Why not me?’ At her event I saw her; she was quite unassuming. But why not her? Why not me? The epic is out there, and everyone’s entitled to it.

When I came to the first pre-Practicum group meeting, ‘Human Limits’, there were no introductions. On the trail later we would all become trekkers, stripped of our social status down to gear and sore muscles. Now the room was full of strangers, business leaders who seemed to all know each other. Konstantin, one of the two familiar faces in the room, smiled encouragingly. I was on edge. What was I doing there..?

Volkov started to explain the layers of the Practicum. The first layer is, obviously, the thru-hiking itself. The Alpine Academy guides, led by Roman Bryk, are responsible for developing the primary route and making any necessary alterations afterwards, working together with local Nepalese guides. I looked at the altitude profile indifferently. If you’ve never been to high mountains, everything seems abstract, and 3000m differs very little from 5000m.

Endurance exercise and altitude affect your physical and emotional state. We had a doctor to monitor the physical part – an addition Volkov had made a couple of years ago, fearing for the participants’ safety. I found our doctor, Alexey Ovchinnikov, to be a strange and fascinating creature. He was an explosive mixture of things noble and ribald. He would watch everyone’s health with an eagle eye, but also randomly recall his time cutting off the breasts of female cancer patients or joyfully proclaim that the trekking goes well indeed, ‘sliding in with no lube’. Volkov endured this with stoic grace. Better to have a trusted doctor with an off-color sense of humor than to risk anyone’s health.

The second layer was socialization. Conversations you fall into on the path can be as important as evening discussions. The composition of our group seemed conducive for a richly varied set of chats: there was a girl from modelling business, beautiful inside and out, with the sort of presence you enjoy automatically; a fair number of MBA graduates; participants who didn’t really buy into the whole ‘intellectual trekking’ concept; Igor Rybakov, a Russian celebrity businessman who played trickster and provoked Volkov to explain the idea over and over; yoga people, a sanatorium CEO, a designer who would sketch the mountains, Inna Yun, and me.

Important as the route and communication may be, they are only a gateway to the third layer, design thinking. During the Practicum, we were to model our professional trajectories and discuss them in abstract, without unnecessary details. This part is the reengineering of self. It is the nucleus of the program. While you can go in any direction you see fit in your presentation, there is an implicit call to think big, to make a change in your professional sphere, to do some good. To stand up and draw your Antarctic on the make-shift flipchart in a room at high altitude.

Every year, Volkov gets more and more frustrated with the lack of intellectual tools participants have for advanced discussions. It is not something you do every day; for most people, it is not something you ever do. There is no guidebook, either. In our work with transformation of universities and other organizations we use a rather well-developed specific method. But people are not organizations. You do not have the luxury of using the collective mind of a large group to design a new strategy. However, you can apply theories of any degree of complexity to your specific problems.

Ideally, you would draw from the most powerful traditions of thought, juggle theoretical paradigms, and stop at nothing to conceptualize your problem (and the problem in your sphere) and the solution for it. For participants to be able to do this, preparation must include filling out your toolbox with whatever problem-setting and problem-solving approaches you come across. Learn the first principles from Marcus Aurelius or Hannibal Lecter, Game Theory from John Nash or A Beautiful Mind, independent thought from Rene Descartes or The Matrix. In principle, besides mountain guides, you’d need an intellectual guide. In this sense, Inna Yun with her combination of philosophical and business training was a godsend.

Preparation went on. The participants started sending out essays, which had to mirror the presentations during trekking: you begin with the context of your professional activity, go on with your personal trajectory, explain the problem you are facing and ways to go around it that you are considering. I tried to write mine a couple of times and failed. In my case, there were no problems, only divergent paths. So I just ran, and read. Eventually, I had my last workout, bought the last item from the list of gear, and flew to Nepal.

In Kathmandu, we were staying at Yak and Yeti. The Royal Hotel, Yak and Yeti’s direct ancestor, was opened in the 1950s by Russian artistic escapee Boris Lissanevitch, and became the first international hotel in Nepal. The place has been a top tourist hotspot and a stopover for various expeditions since. In the hall, we met a group of MIT alumni on their way to trek to Everest Base Camp. Volkov, Konstantin, and myself looked at the group smugly. We are doing the intellectual trekking, we thought. I briefly recalled that Lizzy Hawker ran from Everest Base Camp to Kathmandu (twice!) and instantly felt much humbler.

The route must contain a climax of some sort. For us, this was ascending a 6000m peak.

Volkov, Konstantin, and I had lunch at a restaurant nearby. There I met Ivan Dusharin and Andrei Mariev, our senior guides, for the first time. Dusharin is Master of Sport, International Class, and Mariev is Merited Master of Sport in mountaineering. They sat in front of me, sipping their beer, and looked like giants. I was already used to Volkov, himself Master of Sport, International Class, and was unprepared for how impressed I was by these two. There was an imperial calmness about their presence, a self-collected charisma. I sat very quietly and listened to them talking about the route.

The following morning, we boarded a plane and a helicopter, and landed in Taplejung, our starting point for the trek. We also had our first seminar in Taplejung, helping Rybakov figure out what sort of university he wanted to build. So far, so good, I thought, falling asleep at the end of our first day.

On our second day, we got to ride in jeeps. We were discussing the concept of meaning on the way, but I was mostly occupied with staring out of the window and getting worked up with feverish excitement. When we stopped, it was already nighttime. The stars were bright, and the air was humid and smelled of damp vegetation. Next, we had to descend 2km to Chirwa, a small settlement with a teahouse waiting for us. I was worried. The jumping headlamp light was making me dizzy. So many rocks; where do you put your feet? How on Earth has walking become so goddamn complicated?..

I spent the first couple of days looking down, selecting stones to step on and thinking about the format. I dissected our trekking. What have we got? I went back to the three layers: the route, socialization, and design thinking. To intensify the experience and make you test your limits, the route must contain a climax of some sort. For us, this was ascending a 6000m peak. Should the intellectual part have a climax, too?

Is mountainous terrain necessary? We rarely talked about landforms and flora we passed, and there was little connection between us and what we saw. Many times I thought I would be glad of a botanist’s or a geologist’s company. ‘Why the Himalayas?’, I asked Volkov later. He surprised me by responding with poetic candor: the landscape presents itself in large forms. The sheer scale of things leaves deep marks upon your person and on the way you see the world. Fair enough -- you go to the mountains for Magnitude. Just the same, can you also cross the desert for Inhospitality, footpaths in Iceland in inclement weather for Ruthlessness, Scottish fells for Brutal Beauty, or go long-distance on a yacht for Vastness? ‘What do you think?’, I asked Konstantin. ‘I doubt it’, he replied earnestly, ‘Nothing can really compare to the mountains’. For him, mountains are transcendental.

Why not have a club for those who run far and think hard?

Now, must you walk or can you run and still have full-scale seminars? Running takes more energy than hiking; you are more likely to get injured; the number of willing participants would be much smaller. Still, can it be done? At some point, I had gotten used to the terrain and took to walking at the very front, right behind Mariev who was leading the group. If we were running, I thought, jumping from one rock to another and staggering precariously, I could go faster. In the evening we could roll about on our foam rollers, and discuss speedy transformations and the wind whooshing past our ears! I still harbor the idea. There are clubs for runners who write and writers who run; many a CEO is a running addict; ultramarathoners are high-achievers with ingenious minds (something you can see in how we tinker with our gear). Why then not have a club for those who run far and think hard?

I divided socialization into talking with your peers and with the Masters, which is how I came to call the guides with the highest-level mountaineering experience: Dusharin, Mariev, and Volkov. Now and then they would tell us stories of their expeditions. The stories inevitably involved death. I felt almost physically how difficult it was for me to process its proximity. Modern Western Civilization does not tolerate dying. Philippe Ariès, a French philosopher, classified our attitude towards our mortality as ‘a forbidden death’. We avoid it and shield ourselves from it. And that is just not something you can do during mountain expeditions.

Design thinking can be split into business cases and intellectual tools: new theories, models, and approaches. Some of the evening discussions were devoted specifically to the conceptual framework: how does a seminar differ from a brainstorming session, a work meeting, a conference or trading stories by the fire? What is ‘mountaineering’, really, today? Is it a sport? What is a sport, in the first place? What is a professional community? How does a problem differ from a difficulty? The business cases were more concrete. We discussed the fates of a fitness studio, a design studio, the Russian Mountaineering Federation, and a company in Kamchatka. One participant shared his ideas of how to reform the stagnant housing market. Volkov spoke about our activities with universities.

Our seminars were nothing like academic discussions. If you speak about the changes in your life, you are always at risk even if you carefully avoid revealing what is too personal. You argue with more force and passion. Your perspective is entrepreneurial and engaged, and thus different from that of a scholar. On top of that, in a group of decision-makers, influence is always important. Were we in a standard trekking expedition, your influence would be determined by how experienced, physically and emotionally strong, and sociable you are. The Practicum adds the variable of the strength of your arguments and the clarity of your rhetoric to the mix of factors. Discussions become automatically linked to power.

When we reached Lhonak at the elevation of 4700m, we had to pick one of three scenarios: climbing Drohma Ri, one of Kanchenjunga satellite “hills” with a summit of approximately 6000m, reaching Kanchenjunga base camp, or staying at Lhonak. If altitude was causing too much discomfort, you could also go back down.

Here the question of variability comes into focus. The Practicum is cohort-based. Volkov selects the participants on the basis of professional experience and physical ability. The emphasis on the latter decreases annually but in 2018 the potential ability to make an ascent still mattered. Supposedly, afterward, you can discuss the experience in the group sharing it. Volkov insists that variability fosters deeper reflection -- some participants reflect upon ascending, and the rest upon not ascending. I suspected that intersubjectivity didn’t work like that. If something affects you deeply, you can only truly share it with the people who can relate. Everybody else is an outsider. So I raised my hand for the Drohma Ri group.

Kanchenjunga was right in front of us. The clouds, wreathing, moving, were below.

My climb felt like a broken activity. It was like I was walking on a different planet, one I was not supposed to be on. I was too slow for the first sub-group and too fast for the second, so I ended up ascending alone. I met Volkov, who was going back, near the top. He inquired whether anyone was behind me and quickly went by. His face was emotionless. Something pilgrim in me shattered. So nothing happens at the top, I thought. There is no meaning, no rationale to this. You get up, and then you get down. Mariev appeared round the corner. ‘Let’s go to the top’, he said. I followed him dully.

We climbed a couple of meters up. Mariev stopped. I straightened up and looked around. Kanchenjunga was right in front of us. The clouds, wreathing, moving, were below. White, silver, ochre, and blue. The reality was intoxicating and crisp. ‘Wow’, I said. Mariev’s face lit up, and he said: ‘S goroi’. ‘Congratulations with the mountain’. And just like that, I understood.

The descent was both excruciating and hilarious. Half-way down, my nausea got the better of me, and I threw up. ‘You have to get it all out’, said Mariev nonchalantly. ‘I think that’s it’, I responded, feeling much better. ‘Oh come on’, said Vadim Shcherbak, a participant who joined us later, ‘What about tea? What about those cookies? I saw it all! I remember it all! Go on! It’s a nice spot here, we can wait!’. Throwing up and laughing is actually quite hard. Konstantin, who caught up with us too and was carrying a camera, would ask us ‘to produce more dust’ while walking down, and could we please descend that part again..?

After Drohma Ri, I developed an irritation with rest breaks. A quarter of an hour in, I would look at Mariev, who decided when to start going, and ask hopefully, ‘Let’s go?’. He’d just pick up his poles. When the walking part of the day ended, I wanted to walk more and would trace the contour lines on a map with endless fascination, checking what’s next.

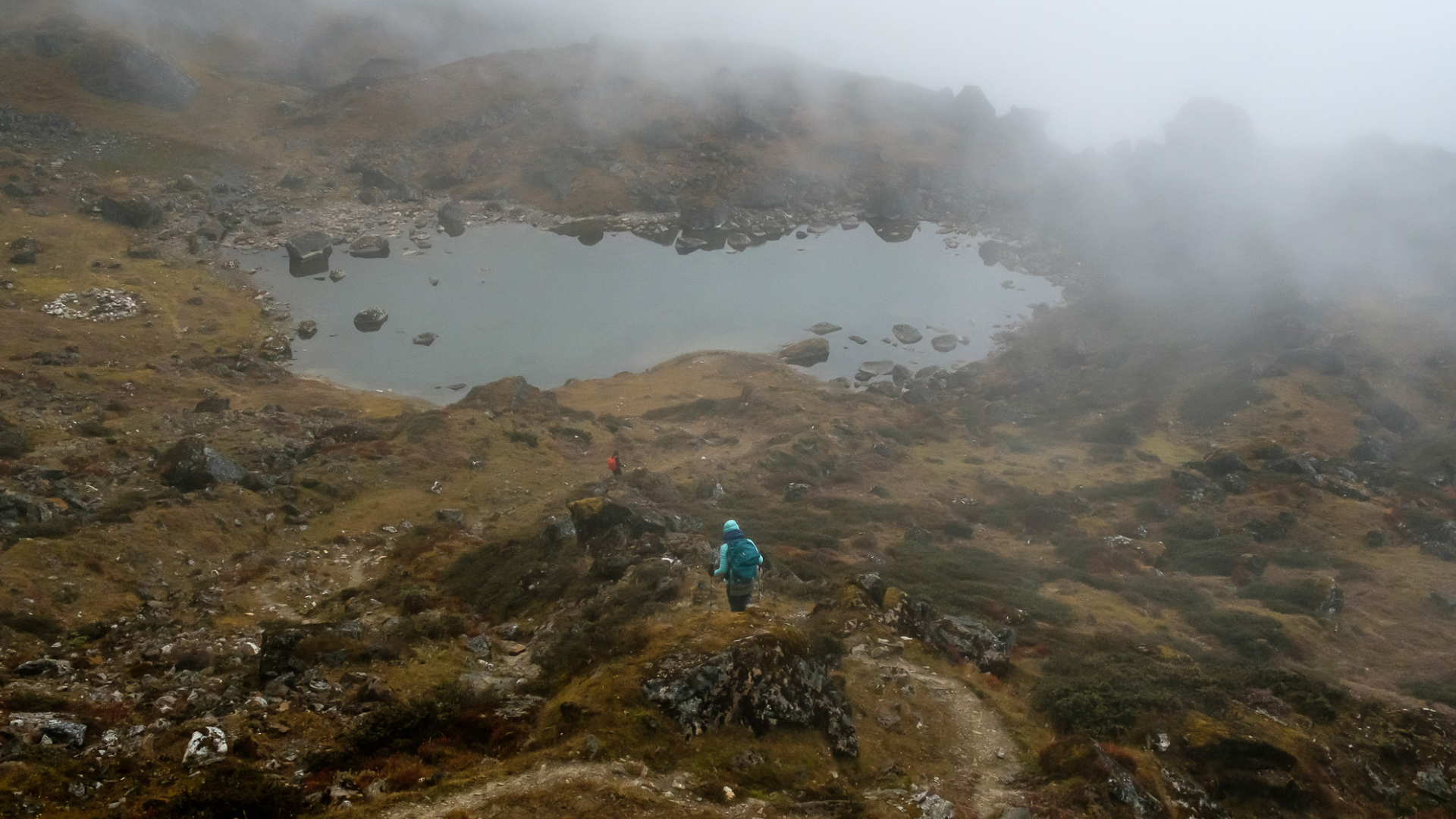

This was a fantasy landscape, and I thought of Ged from Earthsea, Gandalf, and the Faerie.

My favorite day was crossing from Ghunsa to Tseram. The route had three mountain passes, each over 4500m. We were moving in a group of five. We passed an ice-covered wall and a couple of crystal clear lakes. There was fog. In some places, the snow was falling softly on black boulders. This was a fantasy landscape, and I thought of Ged from Earthsea, Gandalf, and the Faerie. This was the place where you dream, and I also thought of the problem with my Antarctic’s gaping absence. Mariev spoke of skyrunning, and mentioned random landforms: nunatak, bergschrund, rantcluft. He chattered in his friendly manner and appeared as gigantic as he did on the day I saw him and Dusharin first -- for some people, there is no gap between who they are and how they present themselves to the world.

The Himalayas would haunt me.

The final day was short and abrupt. We only had to walk about 5K downhill, then spent a couple of hours in jeeps, arrived at our starting hotel in Taplejung and just… stopped. We could get hot showers, and sleep on clean sheets now. My mind could not process it. Everybody was checking their email, laughing happily, and I just stood in the doorway, lifeless. There are things you cannot share, but you wish you could. If I could explain then, I would have said that I was still out there, I was not back. Maybe we never truly come back from our adventures.

The Himalayas would haunt me. For some time, I could not talk about the trip. Something transpired there, at a level deep and primal. Not intellectual, but physical. I had a different understanding of my being. In very simple terms, I learned I was not weak.

It has been a year. I have amassed a couple of shelves of outdoor clothing and gear. I’ve mastered technical descents and waste no time thinking where to put my feet now. I’ve run a couple of stage races in the mountains. There, I got to move as fast as I could, but there were no structured discussions in the evenings. There aren’t running events like that. At least, not yet.

The Practicum did not help me with my Antarctic. It would take volumes of desperation and countless sessions of frenzied strategizing to figure it out. And then one day, the pieces started to fall into place. Antarctics are tricky. You construct them carefully, and then you feel you discover them nevertheless. You choose them, and then end up certain there never was a choice. I like mine. The damn thing is difficult, and right, and larger than life.

Post-scriptum. This story has been written in strokes, bits and pieces, in hotels, airports and airplanes. No wonder it is not cohesive! I could have written about Alexandr Yurkin, another guide who took care of our lodging and meals, and written more about Roman Bryk or Ivan Dusharin. I would also like to be able to tell the stories of each of the participants, intertwine them with mine, but I cannot. I was simply too self-absorbed. (If you are reading this, I wish I had gotten to know you better!) Some things are consciously omitted. I did not feel I had the right to render personal presentations and discussions that followed. The ‘Masters’’ stories should remain where they were told. I deliberated and decided not to write about how gender plays out in mountaineering, something that was surprising and hopelessly confusing. Now, the Ph.D. program I quit is the best in the field, and I am immensely grateful for the time I spent at Boston College. Quitting is perceived as the result of a disagreement or a failure in our culture, but this has never been my perspective. Quit books, jobs, places, and lovers that are not in sync with you, however good they are! Quit amicably, and it will be better for the both of you. Finally, this piece looks so neat because Nicholas Byrne has helped me edit it, with care and attention. Gee, that is one long PS!

Follow Dara on Facebook

Comments ()