The Mystery of the Solstice Cave

Perched high on a San Diego desert hillside, a cave with a trove of indigenous history awaits -- if you can find it.

Rain gently pattered on my wide-brimmed hat as I stopped to catch my breath, surveying the surroundings to visualize the most reasonable next move up the boulder-strewn gully. The wind, calm on the leeward side of the mountain, could be heard, but not felt, roaring over the mountain passes above me. Light, yet persistent, raindrops made for difficult hiking conditions on the slick rock, and a backpack loaded with overnight supplies threatened my balance if I were careless with my steps.

With no maps or trail markers, I was just going off a vague description of my desired destination. I was searching for the solstice cave — a natural rock shelter that was sacred to the Native Americans that once inhabited this harsh desert landscape of eastern San Diego county.

With each muscle-wrenching hop from boulder to boulder, my confidence began to wane that I wouldn’t be able to pin-point the cave’s coordinates.

The Kumeyaay people, who have inhabited the greater San Diego area for 10,000 years, left their markings in the solstice cave. The ceiling of the rock shelter features an array of paintings, known as pictographs, that tell a story of the cave’s significance, providing a glimpse into the life of ancient California.

It’s this mystery and allure of the cave paintings that drew me to this remote canyon, searching for a particular boulder, among thousands. Essentially, I was seeking out a needle in a haystack, a needle that could serve as a portal into a not-so-distant past of the region that I call home.

Earlier in the morning, as I was passing through the wide, sloping valley below, I knew that I was hot on the trail of the solstice cave. I meandered through the cholla cacti and ocotillo, jack rabbits darting from side to side, observing abounding evidence of past Native American habitation.

I came across two smoke-stained caves, each with morteros (grinding holes used to crush nuts and seeds), tell-tale signs of ancient Kumeyaay campsites. There were additional grinding holes that I found in the nearby palm filled valleys.

When I reached the end of the valley, the flat, sandy earth was replaced by piles of large granite boulders that rose thousands of feet into the peaks of the In-Ko-Pah mountains.

Scrambling up the canyon of boulders, I knew that somewhere near the top, a thousand or so feet up, the solstice cave could be found on the southeast-facing slope.

As daunting a task it may seem, the solstice cave has a unique feature that facilitates its discovery. A thin, pointed piece of granite extends out from the cave. This rock feature, which some people online hypothesize was used as a sundial, protrudes towards the canyon, visible from below and the closest thing to a beacon that you will get.

After quite a bit of arduous scrambling over boulders, I looked up to see this ‘sundial’ a few dozen meters above. A sense of relief began to brew within me. I had found the solstice cave.

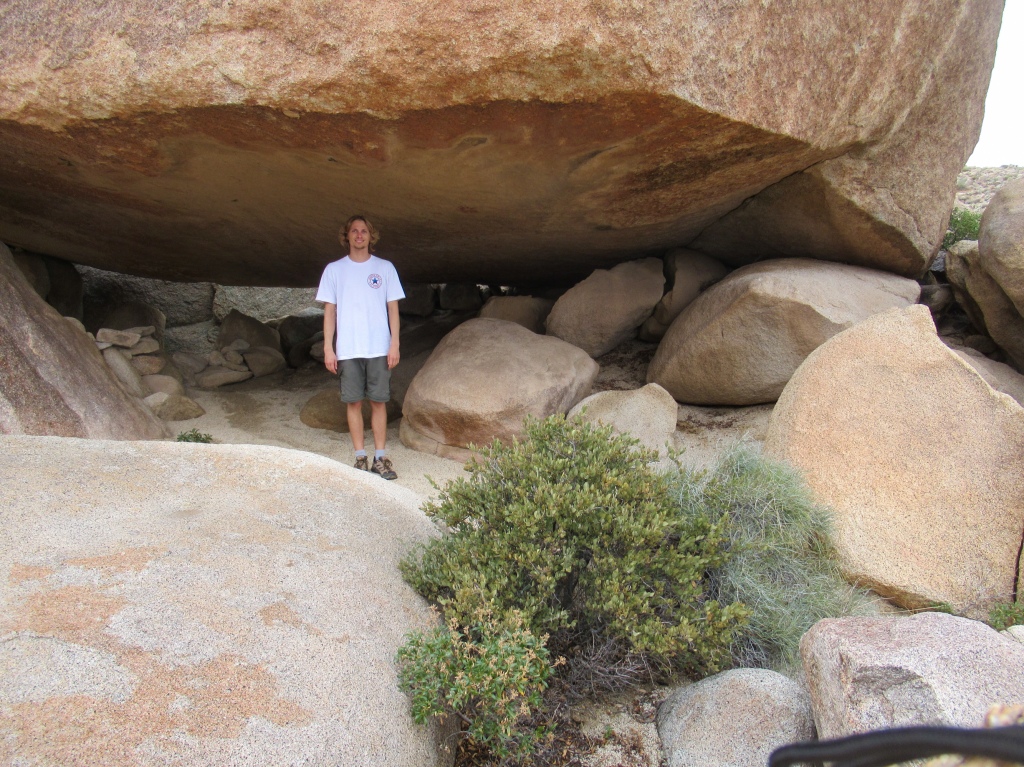

Laying my eyes on the solstice cave for the first time made all the photos that I had seen online come to life. A weathered granite boulder the size of a small house balances on a hillside, teetering on other large boulders that appear to have all been part of one large rock before the erosion of time split them apart. The shelter stands over two meters high at its entrance, becoming increasingly smaller towards the back. With ample space to provide protection from the elements, the solstice cave has a sweeping view of the low lying Colorado Desert to the southeast — the general direction of the rising sun. Then, of course, as you take a closer look at the cave’s ceiling, the rock art comes to life and tells a story, hundreds, or thousands of years old.

Sitting in the cave provides a calming sense of connection with the ancestors of this land. In the US, we don’t have the ‘luxury’ of being surrounded by the physical history of our country’s predecessors, not like the “old world” where walking past thousand-year-old buildings is part of daily life. Getting to experience California’s version of ancient civilization is unique and rewarding, yet simultaneously somber knowing how the chain of events played out.

I gazed upon the pictographs and imagined hundreds of years ago, someone sitting right where I sat, running their fingers along the granite, looking out at the same desert landscape below.

The cave paintings consist mainly of suns, placed in locations that are believed to predict or relate to the sun’s cyclical positions according to the season, perhaps indicating the solstices or equinoxes. I was at the cave in the afternoon on a cloudy day, so not a time to observe the patterns of shadows cast on the ceiling.

Red and orange-hued suns are placed throughout, with other forms, some seemingly human, found in the back of the cave. The beauty of the rock art is that no one truly has the answer to its meaning. It’s an open book, open for your interpretation, putting yourself in the shoes of the artist.

I didn’t have all day to examine the cave, but I took a valuable thirty minutes out of my trek to take it all in. I still had a lot of ground to cover before dark.

Finding the solstice cave was rewarding. It’s always fun adding a treasure hunt to a hike, and even more interesting when it combines a history lesson as well.

For those who are interested in learning first hand about the Native American history of California, or simply are looking for a good reason to do a challenging hike, get out in the nature of San Diego and experience it for yourself. Hiking around San Diego for years, I’ve learned that you just need to open your eyes, know what to look for and where to look. Every mortero, pictograph, and artifact has its own story to tell.

This article first appeared on the author’s website: www.evanquarnstrom.com.

Comments ()