Kalap: Following the Mountain Goat in India's Himalaya

This is the story of a man's earnest attempt to improve the life of a remote village in the upper Garhwal region of North India; a story of responsible tourism in Kalap.

"Do you know how these forest trails are created?" asked our guide, just before we began the slushiest part of our journey. Fat pellets of rain smacked our heads and backpacks as we tried to make our way up the forest. In our oversized ponchos, we looked like a bunch of helpless ghost busters.

”The goats and sheep urinate continuously on the tracks while walking in a single file, producing urea. Plants can't grow in urea infected soil after it crosses a certain limit. Voila, herd trails are formed,” our guide grinned and walked up.

In the early 1990s, a woman from India’s southern city Bangalore abandoned her husband, and with her three young children made her way up north in the Himalayan region to start a new life. She decided to set herself up in a village called Kalap in the upper Garhwal region of Uttarakhand in North India.

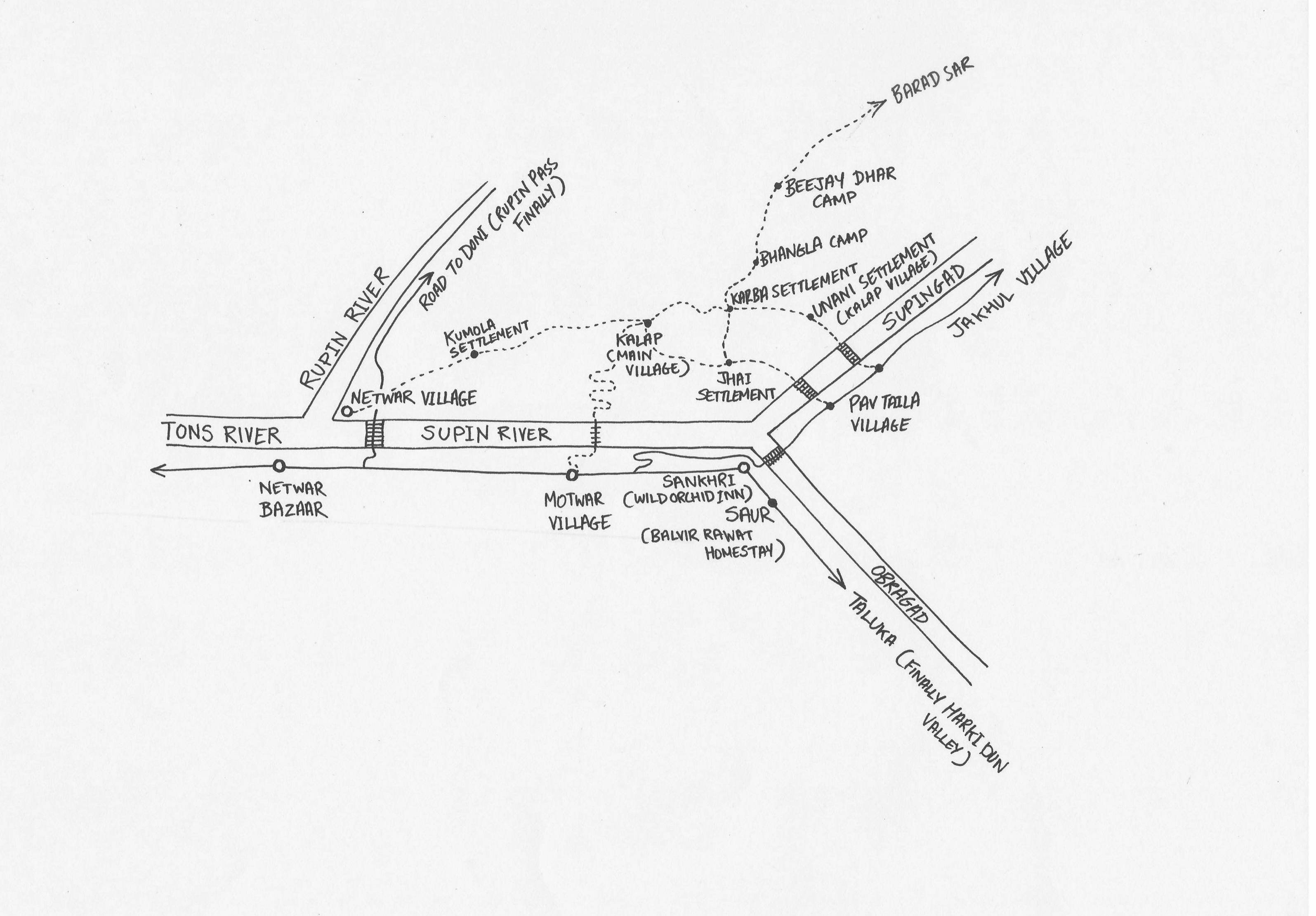

They settled down in the lowest part of the village, in the settlement of Dhawla (4500ft) which is on the banks of the Supin river, a roaring tributary of the Tons river originating from a glacier in the Bandarpunch range in Garhwal Himalaya. The village of Kalap has four main settlements - Dhawla (4500ft), Unani (6500ft), Karba (8500ft) and Kalap (7800ft).

She and her three kids built a house of mud and stone right by the banks of the river on land donated to them by the community. They grew their own food, raised cattle and set up a water pump from the river up to the house. They later upgraded the house to a pucca structure and installed a solar panel on the roof for electricity.

[gallery type="rectangular" size="full" ids="5905,5904,5903,5900"]

All went well until 2002. That year the monsoon forced a fatal cloudburst to hit the river. It caused a massive flood, destroying the lone iron pedestrian bridge that connected all settlements in the Kalap village to the the other side of the Supin Valley where the road is. Access to the road is considered a lifeline for the village settlement.The iron bridge provided a shorter route to the road. Since it was washed away, a new one has not been built. Instead, the village folk build a make-shift wooden bridge every winter to cross over. This bridge lasts about six months. Monsoon takes over and it has to be built again. Without the bridge, the villagers have to walk five extra kilometers to reach town.

After spending 15 years by the river, the mother and her three kids packed up everything and left the settlement. One of the children, Naren grew up to become a school teacher in Dehradun and was good friends with Anand Sankar. Anand, a photo journalist based in Bangalore at the time visited the region with Naren in 2008. By June 2013, noticing the immense potential it held for 'responsible tourism,' set up shop in Kalap.

[gallery size="full" type="rectangular" ids="6187,6103,6807"]

Kalap is the main village, 4.5 kilometres above Dhawla. It is home to almost the entire population of the village with 100+ houses. The settlements of Dhawla, Unani and Karba are where people have their seasonal agricultural homesteads called 'chaan' locally. The entire Gram Panchayat (cornerstone of the local self government) of Kalap is massive, about 14 kms in length from end to end, and it takes an entire day to walk from one end to another. The 2011 census counted 469 people in the area.

[gallery type="rectangular" size="full" ids="6109,6096,6106"]

Bangalore-based Anand used to be a journalist before he briefly ran an outdoor enterprise for corporate offsites on the outskirts of the city. His passion for motorcycling and his stint in photojournalism gave him opportunities to travel the length and breadth of the country in his 20s. When he visited Kalap, he saw an opportunity there. “This part of the valley is pretty unexplored. That’s because of its remoteness. The only way to reach the settlements is on foot. The people here are pretty self-sufficient, it is one of the few villages in Uttarakhand where barter-system works, and when I started exploring, I could sense this would become a good enterprise. So I just went with it."

In early 2013, Anand packed his bags and with his two beloved cats made his way to Dehradun, where he created his ‘office space’ and a home base. He explored the region thoroughly, set up the Kalap Tourism Project, employed three full-time local staff and created slow-travel experience itineraries that include home stays, trekking and camping.

Kalap Tourism Project was officially launched in June 2013.

[gallery type="rectangular" size="full" ids="6122,6119,6118"]

We were moving up a trail that Anand (who was also our guide) called The Nomad's Trail. It was called The Nomad's Trail because it is often used by nomadic shepherds and locals, but has remained unexplored by outsiders.

[gallery type="rectangular" size="full" ids="6131,6129,6124,6123,6120"]

We started in Kalap at 7800 ft, moved up to the second settlement of Karba at 8500 ft, walked through forests of fern and maple, crossed streams, slipped and fell on wet rock, climbed up forests of blue pine, where the hum of cicadas and the murmur of streams were the only sounds apart from our own heavy breathing; reached a massive meadow called Bangla at 10,000ft and camped overnight. Anand proudly claims that apart from the locals or Gujjars (nomadic group), no outsider walks these trails.

[gallery type="rectangular" size="full" ids="6135,6136,6137,6140,6141,6143"]

The next morning, we headed back into our set-up of the Hunger Games forest of blue pine. The trails were invisible but Anand seemed to know where to go. The air was intensely humid and the sky a greyish white. It rained. We climbed over fallen trees, crossed streams and emerald pools, again slipped and fell on wet rock, hiked up through tall grass and slush and wet mud, up and up till we reached a clearing - a meadow laid out like a green carpet with big brown oak trees on either side, and in front of us a feast of mountain ranges - the entire Garhwal range. We climbed an endless flight of stairs made of stone and reached a height of 12000 ft in a place called

Beejay Dhar,our final camping spot. The spot is called Beejay Dhar because the sheer cliff behind it is famous for sightings of musk deer called 'beejay' locally.

[gallery size="full" type="rectangular" ids="6146,5899,6149,6150,6153,6154,6156,6159,6161"]

Nitin, Tanraj, Ruhani, Nikita, Renu - five little rascals show me around their village Kalap at 7am. They run barefoot on the uneven surface, up and down, hop over boulders, pose for photographs under waterfalls, climb trees and throw their favourite fruit chulu (wild apricot) at me to eat. They have their summer vacation on for a month. They hang about the village and help their folks in farming, rearing the cattle and carpentry. They do have a lot of homework to finish. Basanti, 12, told me that she had to write dictation in Hindi and English, count to 25000 in writing for Math and write tables up to 25.

[gallery type="rectangular" size="full" ids="6184,6173,6178"]

The people of the village enjoy a barter system, grow their own food and raise their own cattle. They live on a diet of mostly beans and grains. Fruits like plum, wild apricot and apricot are occasionally grown. They build their own houses. The houses are three-tiered striped structures made of mud, deodar wood and stones. Every house has carvings, apparently considered a status symbol. The more elaborate the carvings, the more respectable the house. The three tiers are for different creatures - the bottom one belongs to the cattle, the middle one belongs to goats and the top one is for people. Where cattle reside, ticks and flies are bound to be found. On our first night, my friend found herself bitten by ticks from head to toe.

[gallery type="rectangular" size="full" ids="6180,6183,6177"]

Life in the village, though calm, is harsh. Lack of connectivity by road makes it tough for the locals to get hold of basic amenities and medical healthcare. Even school teachers at the local school would run away without informing anyone, leaving the children with a constant uncertainty. Assessing the situation, Anand decided to form a non-profit organisation called Kalap Trust in September 2014 when he saw that the village had pretty much everything except good education and medical facilities. He launched a crowdfunding campaign, set up a school with two teachers and set up a medical clinic with a doctor who would start diagnosing the problems of the villagers, which are aplenty.

[gallery type="rectangular" size="full" ids="6193,6098,6194"]

He has employed two experiential educators to provide after-school classes to the kids. At the moment, Anshu Agarwal and Ashwini Govind work as teachers. Students gather inside the ring hall, an area in the centre of the village for play at about 4pm almost every day. The classes are full of surprises for the children. Apart from the regular English language lessons, they are sometimes made to watch films - mostly animated, and hold discussions around them. Their current favourite is Thor. Ashwini, an environmental scientist and an art-and-craft enthusiast makes it a point to teach the kids something on their environment in every class. In her last class I attended, she had created illustrations depicting the story of an ant in various seasons. The 26-year-old has made her way up to the village all the way from Bangalore to spend a year with the children. Having gotten used to the cold and tick bites, she loves her job and aspires to continue teaching children the ways to work with and love nature.

[gallery type="rectangular" size="full" ids="6186,6188,6176"]

After spending two nights on Beejay Dhar, we made our way down, back to Kalap. On the way back we spent a night in a homestay in Karba, and made friends with an old lady who showed us how to spin wool. This remote village of Kalap is gaining recognition on the world wide web thanks to the enterprise. My hope is that it develops well for itself, maintains its beauty and self-sustenance and does not turn into a commercial chaos that several North Indian hill stations are known for. That seems unlikely given the area has no road connectivity and most urban dwellers are suckers for convenience. For the sake of this village, that might be a good thing.

You can help the folks of Kalap Trust by continuing to donate for their trust here.

Feature Image: Glorious sunset in Beejay Dhar (Photo Courtesy Swati Chauhan/ The Outdoor Journal)

Images: Swati Chauhan/ The Outdoor Journal

Comments ()