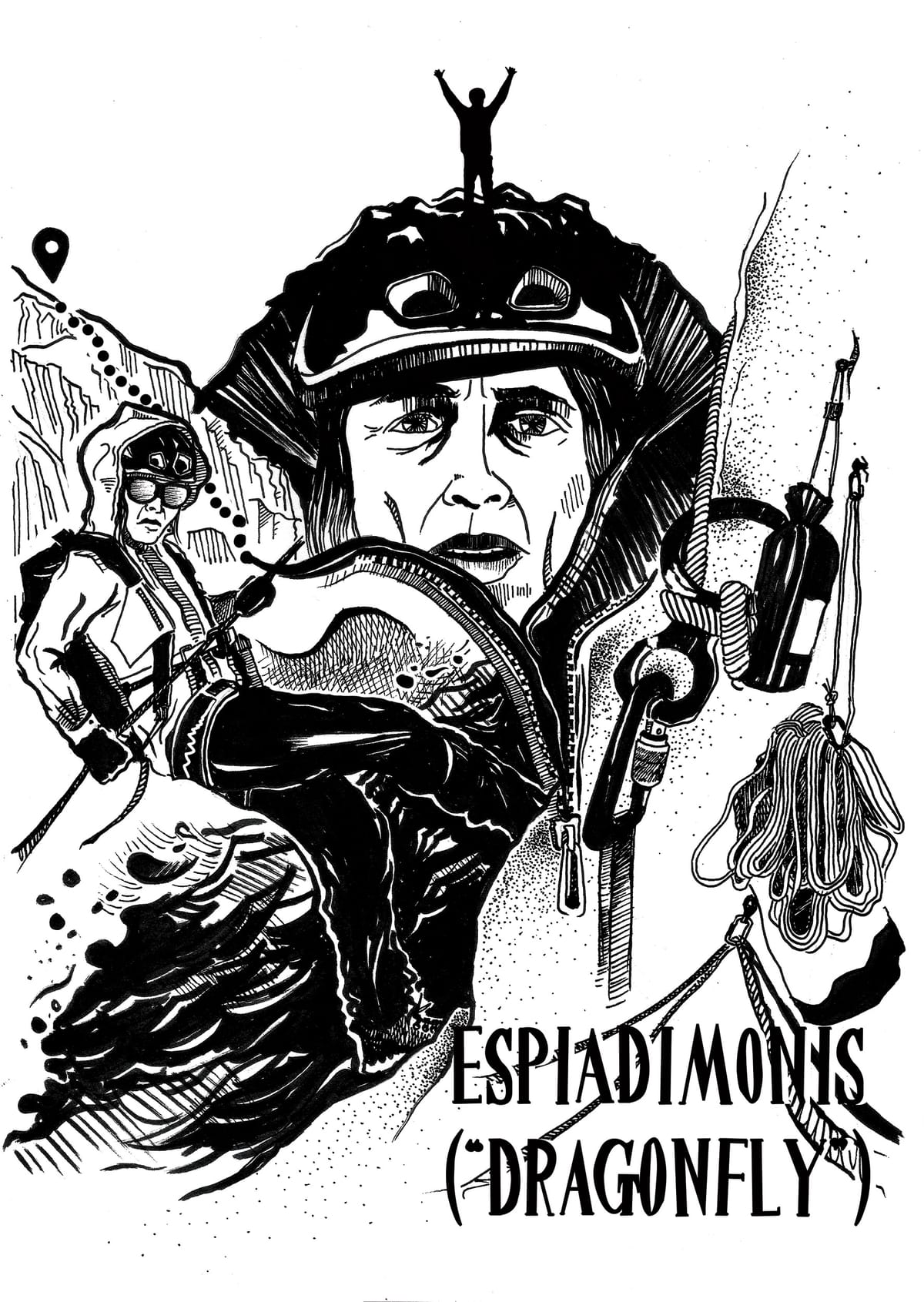

32 Days Alone: Silvia Vidal’s Patagonia Big Wall

This is a tale of isolation, patience, grit, happiness, pleasure, and uncertainty. It usually takes Silvia Vidal half a year to recover after an expedition. However, after climbing a wall called “Serranía Avalancha” in the Chilean Patagonia, it took a lot longer. It wasn’t one of her run-of-the-mill epic climbs, but an incredibly intense adventure.

It always takes my body half a year to recover after an expedition. But when I returned home after climbing a wall called “Serranía Avalancha” in the Chilean Patagonia, it took longer. It wasn’t just a climb, but an intense adventure. It is hard to recount what I experienced there, and once you begin narrating the story, you simultaneously put it away in a drawer of memories.

The approach was hard because we had to use machetes to pass between the reeds and forest trees (in the Valdivian jungle) and make landmarks in order to find our way back. In such thick vegetation, you don’t see much beyond a few feet. Your passage is barred constantly, by rivers, both broad and narrow, by the 300 kilograms of equipment, and by the food and the boat that must be carried. For this approach, I hired two Argentine climbers (Dani and Dante), who helped carry the load.

On the second day, we reached a lake, at the other end of which stood the wall. I decided to establish my base camp here. My approach team returned at this point, and for the next month and a half, I was totally alone—no cook, no photographer, no climbing partner, no visitors…no one. Total solitude for a long time.

I spent the first two weeks fixing 350m of the wall and watching the rain fall. These days were a prelude of what was to come, as I had to stay inside my tent for most of the time and could climb on only a few days due to the heavy rain. I also needed to row from base camp to the base of the wall, and sometimes it was too windy. I am not an expert rower and I can’t paddle straight.

When I first reached the wall, after several tries, I was forced to leave my haul-bag in the boat. I had packed it without calculating the terrain, assuming I would find a good spot from which to haul it off the boat. But on the vertical rock such spots did not exist, and the bag proved to be too heavy and the manoeuvres too awkward.

I spent all of the first day climbing the initial section of the great wall, which turned out to be 1,300m in its entirety (plus 200m of easy terrain to the very top).

That first day I climbed under a drizzle, and when I returned to the boat at night, my clothes were totally wet. This became a routine pattern during most of the nearly two months I spent there.

Luckily the sun would come out occasionally, and when it did, I was able to dry off. It was crazy how quickly the weather could change. One day could be sunny with a temperature of 28ºC, but the next day could be snowy and freezing. Although it mostly rained and the temperature was never that low, the constant humidity still made me feel very cold.

Finally, on 8th February, I moved from base camp to the wall with the intention to remain there until I either got to the top or was forced to rappel down for any reason.

I was well informed about what I could encounter on this trip. I was aware of the jungle and the approach, of the wall that rises directly from the water, of the weather conditions, and the very real possibility of climbing big wall style.

I had been warned that trying to set up portaledges on the wall was not a good idea because of the “waterfalls” that make it dangerous. It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say that “rivers” flow down the wall when it rains. And so I chose a line with more roofs because this offered valuable shelter. While Camp 1 on the wall was well protected from the rain, Camp 2 was fully exposed, and therefore I suffered. Once I was beyond the roofs, I was drenched with water falling from all directions. I spent the nights on the portaledge dressed in my Gore-Tex jacket and pants, inside a bivouac bag, and still water made its way inside my sleeping bag. I felt like I was in a swimming pool.

For several days, I watched the storms and jets of water streaming down the face from the portaledge. This sight was the cause of my despair. Then dawn would break into a sunny day, and everything would acquire another color—blue. And then it was time to climb again. And so, I kept climbing and kept progressing. Fortunately, I had food for the 32 days that I spent hanging on the wall. Sixteen of them were days of total inactivity, but as I had expected there to be so much rain, I had brought more food and less water. This allowed me to hold out for such a long time on the wall.

I never bring any kind of communication device during my expeditions. No radio, no phone, no Internet. This leaves me totally isolated. If I am going alone, it is because I want to be alone and feel alone. To bring a phone would have changed my commitments and my entire experience. This is a personal choice. It also comes with disadvantages, like making a weather forecast unavailable. And this makes things a lot harder when you need to plan a summit ascent. Your chances of success are diminished by the lack of information.

On the 28th day on the wall, after ten days of continuous rain, I had to weigh my options and decide to either end the climb and rappel off the wall, or continue upwards. I had no idea when the weather would change. During the previous ten days, I had been optimistic, thinking that the next day would bring sunshine. But as the days passed, I started to worry and eventually had to make a decision. I was stuck at a 1000m from the ground. I couldn’t climb but I also couldn’t quit the route as I had all my ropes fixed above the portaledge. If good weather came, I needed to decide on either climbing up to retrieve my ropes and beginning a 3-4 day long descent, or continuing with the climb to the top and then rapping down. Too many days and too much uncertainty!

Finally it stopped raining and I was lucky to be able to reach the summit and also to rappel down, but not without trouble, as I had to twice cut a rope that got stuck during the descent. I must apologize for the gear that I left up there. Everything else, from the wall as well as base camp, excluding the rappel belays, were removed. It took me 3 days to rappel down the route with all the equipment. Due to the characteristics of the wall and the route’s line (which included roofs and traverses), the descent was very complicated. It was made even harder by the large haul-bags and the solo manoeuvres, which took that much longer.

I recovered the boat, inflated it and started rowing across the lake, back towards camp, back “home”. The next day I started the walk out with the first of the five 25kg bags that I would carry down. I had badly injured my knee after so many days laying on the portaledge and with my overall weakness, I began to complain about the weight of the load. The descent took me seven limping days to complete.

When I got to the first river it was totally impassable. The water level had increased due to the rains. If it continued raining, as it was at the moment, I would be unable to cross and this would be a big problem. Without really thinking about it, I returned to base camp with the intention of continuing with the loaded carries and then seeing what would happen. After some days the rain stopped and I was able to cross the river, but, again, not without difficulty. I had to cross back and forth nine times in order to ferry all the equipment.

Once I got everything on the other side it started to rain again. This worried me because I still had to cross the main river, the one that was at the end of the trail and close to the road. That one was much larger and wider. With all the haul-bags lined up along the final river, I tried to cross it. But the river had risen too high. Forced to leave everything just 100 meters from the car after seven days of hard work and destroying my leg, I felt very sad. This was difficult to digest, but I was glad I had at least arrived so far.

I was thinking of what I should do when suddenly I saw a blackhoe that had begun to cross the river. The driver signaled me to approach. A group working on the road had seen that I was in trouble and so they decided to help me. I couldn’t believe it. This was the first group of people I met after so many weeks being alone and they were helping me without any knowledge of what happened. This increased my faith in human beings. I was put up inside the cabin. This was an unbelievable situation - I felt as if I was watching a movie.

There had been situations of no return, isolation, moments of uncertainty, and several other difficulties to face. All these tested my patience, among other things. But, because I had a desire to be there, there had also been many moments of pleasure, happiness, surprise, and excitement that made me feel comfortable. And doubt and uncertainty were necessary to increase this desire. In such an intense experience the tough moments only deepened the sense of challenge. And a challenge is very motivating. This wasn’t just a climb. It was an intense adventure.

Feature illustration by Naveed Hussain

This story was part of the Features section of The Outdoor Journal Summer 2015 edition of the print magazine

Comments ()