Don’t Move or You’re Dead

Forrest Galante showcases his wonder for wildlife around the world to benefit species that science has all but forgotten.

Long before he set out to rewrite natural history by nosing out animals that the scientific world has deemed extinct, Forrest Galante learned to fish in Zimbabwe with his grandfather, a skilled bushman “with a sure sense of how to conduct himself in the wild.”

One day as a boy, his grandfather took him on a special trip to the Mana Pools National Park on the Zambezi River to test their luck looking for tigerfish, a particularly prized game fish that, like piranhas, have interlocking, razor-sharp teeth.

While Forrest went about eagerly casting spinners into small eddies, a giant bull elephant followed him down the same gully for a drink, cutting him off from camp.

“Don’t move. If you run, you will die.” Forrest’s grandfather whispered while they stood only 15 feet from the grey behemoth.

Eventually, the “elly” had its fill and moved on, but the experience made a life-long impression on Galante. [Read more about Galante's narrow escapes from death in Part 1 - At Home in the Food Chain.]

Just this month, Galante assisted the Ivan Carter Wildlife Conservation Alliance (ICWCA) in the first-ever elephant translocation between two conservation areas within Mozambique, Africa. The project relocated a multi-family group of 25 elephants, who suddenly found themselves in direct human conflict.

Although Galante traveled to Mozambique with good intentions, he left in haste when a local politician put a price on his head based on the belief that Galante intended to expose illegal government operations.

“We’re literally on the run from someone trying to get us.” [Listen to the podcast on Spotify or Apple]

Evading human threats is part of the job description for Galante, who faced a similar situation in Myanmar after he answered a remote village’s call for help to track a man-eating croc.

“I’m going there to help a village with a man-eating crocodile problem and before I know it I’m running away from a corrupt politician and the military who’s put a price on my head because of their illegal logging operation.”

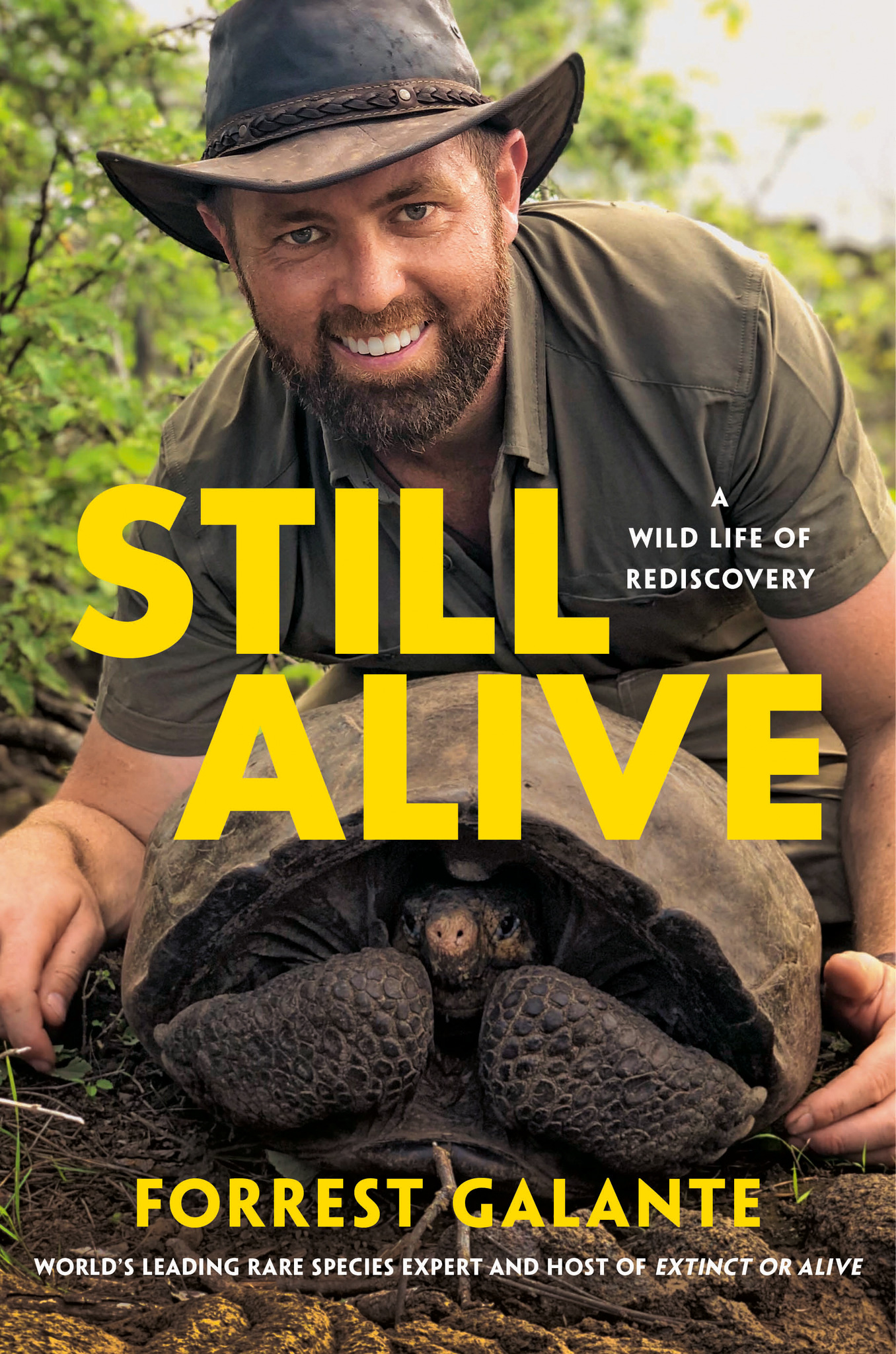

In his book Still Alive, which was released on June 1, Galante reflects on his life trajectory as a barefoot boy in the Zimbabwean bush who developed global ambitions to inspire others to support conservation by sharing his love for nature. His discoveries of extinct species do just that.

As if by a destined hand, Galante’s boyhood of flipping logs to catch cobras perfectly prepared him for his career as the host of Animal Planet’s Extinct or Alive, where he ventures into the most remote and wildest places left on Earth to find animals that humanity has given up for extinct.

Despite his passion and altruistic enthusiasm to promote animal conservation, it took Galante two years of pitching the concept for his show Extinct or Alive just to get a ‘Maybe.’

“I don’t like taking ‘No’ for an answer.”

Galante has rewritten natural history eight times, as his show has occasioned the rediscovery of eight lost species, which carries on the legacy of his grandfather, who played a part in the discovery of the coelacanth, an ancient fish thought to be extinct for 66 million years. In the 1950s, his grandfather traveled on vacation to Comoros, an archipelago of volcanic islands situated off the southeastern coast of Africa. While he was perusing a fish market one day, he noticed an odd-looking fish. Although he was not a trained biologist, he followed the steps to maintain one of the first intact, non-rotted specimens of a coelacanth on record.

“I’ve modeled my behavior after my grandfather, after that idea that you do what’s right regardless of the cost and in my mind, what’s right in 2021 is conservation.”

The deterioration of ecosystems and the extinction of species are symptoms of Western culture’s disconnect from the natural world, one that focuses on conveniences over conservation. He hopes that his children can lead a life similar to his own roots, but that might not be possible in California.

“I have a son who is a year and a half and we are literally thinking about leaving the western world.”

Even as a young child, Galante was self-reliant, a trait that he sees is lacking in today’s culture. He would leave home each day without packing a lunch because he had learned the skills to fish and forage for his own food in the wild.

“I want to take my kid and shove him in the bush in Africa with a pellet gun and a fishing rod and say ‘Get out of here, go figure it out,’ because I feel like you learn so much more that you become so resourceful and dynamic and you garner skills of persistence that you otherwise don’t get in the Western world.”

Galante relies on these skills he learned as a boy in Zimbabwe to find things that don’t want to be found. In 2019, he discovered the crown jewel of the Galapagos, a female Fernandina Island tortoise, an animal that had not been sighted since 1906, with only one specimen on record. Discoveries like this are not just species-specific, they challenge our modern definition of extinction.

To Galante, the fundamental problem is not corporate practices or political dealings, it’s the Western mindset.

“The God complex, which we all have, creates a false arrogance that we are better than the environment.”

He proposes that perhaps experience in the outdoors, a truly humbling experience, is the answer.

“Get into the middle of nowhere, put down your tools, your weapons, your tents, go walk with elephants, go run with lions, go see who's the master of the environment. And getting put into the food chain is so humbling. It's a reality check that you are just another living organism.”

Read next on TOJ: Human Lives Are Not More Important Than Animal Lives

Throughout his book Still Alive, Galante makes it a pattern and practice of ignoring the predetermined risk assessments on his travels.

“The way I assess risk is that I look at a situation and try to find out where is the line and how far can I tip-toe over it.”

Galante nearly became paraplegic jumping from a waterfall in northern Thailand, which was only one of the occasions where he suffered temporary paralysis. In a spiritual way, he feels that his work in conservation has earned him some lucky breaks to survive these extremely close calls. Or perhaps that mysterious green powder he snorted in an Amazonian Shaman’s hut really did have mystical powers. [Order your copy of Still Alive here.]

“When I travel around the world, I'm a scientist, so I don't believe in voodoo and witchcraft and Joo-Joo and all of these things, but I respect the hell out of it.”

Galante leans hard into the philosophy of Biocentrism, the world view that considers humans to be of no more value than any other particular species of animal, as opposed to Anthropocentrism, the view that considers humans to be the most important factor and value in the universe. However, Galante does distinguish between the value of animal species depending on their place in the food chain.

“All lives are not equal. If you are an apex predator, at the top of the food chain, you are more biologically valuable than something at the bottom.”

From a layperson's perspective, this stance may seem difficult to reconcile with biocentrism, yet from a person who has dedicated his life to wildlife biology and conservation, it’s cut and dry.

“If you care about the planet, you have to understand that certain life, biologically speaking, when it comes to species, is more valuable than others within an ecosystem.”

It might sound counterintuitive at first, but Galante is not against hunting, in fact, he’s an avid free-dive spearfisher.

“It's the most sustainable form of harvesting protein on earth. You select one. There’s no bycatch. One animal feeds me for many months. It's clean, it’s sustainable, but it’s important to do it ethically and legally. Those two things are not the same.”

Selective hunting and fishing fit within this conservationist’s lifestyle for the very reason that it is a more sustainable choice than dining out.

“It's way better than going to Nobu and spending 85 dollars for two pieces of sushi from the same fish.”

Yet Galante admits that it’s not fair to impose universal conservation expectations on Western society as well as developing nations.

“Conservation is a luxury. That train of thought can only come when our basic needs are met. It doesn’t apply in areas where people don’t have alternative options to eat.”

To those that can afford it, daily choices can make a difference if we are all in this together.

“There are thousands of small choices that you could make in your daily life. It’s not one person being perfectly sustainable that’s going to make a difference, It’s everybody doing it imperfectly that’s going to make a large, global difference.”

In this episode of The Outdoor Journal Podcast, Galante discusses his fish out of water experience as a young teenager moving from Zimbabwe to California, his rise from counting ants under a microscope for a living to making a speech about human-animal conflict mitigation to the Senate committee, and why Galante has the confidence to follow his personal moral code even when it clashes with local customs.

Still Alive released on June 1, available here.

Read more about Forrest Galante in Part 1 - At Home in the Food Chain.

Follow Forrest on Instagram @Forrest.Galante

Follow Forrest on Facebook @ForrestGalante

All photos courtesy of Forrest Galante

Comments ()