Kayakers Become Conservationists to Save Hemlock Trees

Hemlocks in many inaccessible riparian areas in the Southeast are threatened by an invasive parasite. In a unique pairing between conservation groups and kayakers, they can be accessed and saved.

The kayakers listen intently as a Hemlock Restoration Initiative staff member describes hemlock treatment protocols, before carefully packing treatment materials, including insecticides, in special waterproof bags. They begin the long trek down to the Green River Narrows, a challenging section of whitewater. The kayakers are members of Team PHHAT, the Paddlers Hemlock Health Action Taskforce, a group of volunteers combining kayaking and conservation. Their mission? To save hemlock trees from a deadly invasive parasite in areas only accessible by boat.

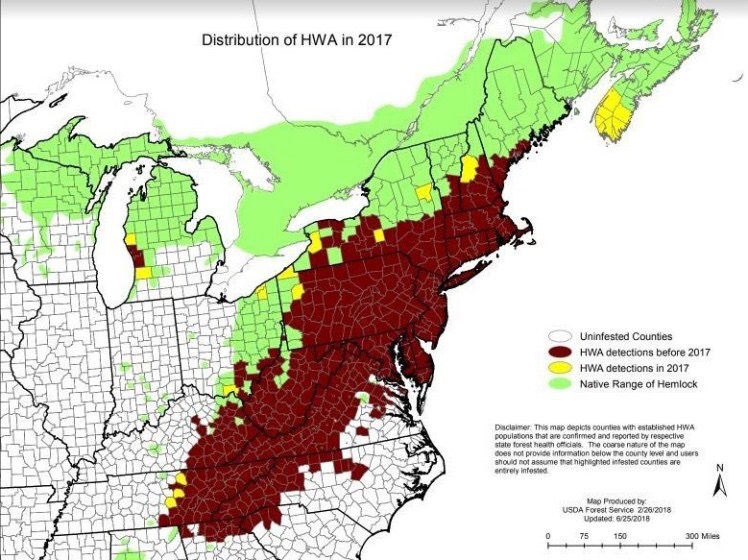

The hemlocks along the Green River are threatened by the hemlock woolly adelgid, a non-native invasive insect originally from East Asia but first introduced in the United States in 1951. The hemlock wooly adelgid infestation has since grown to include parts of 20 states from Georgia to Maine.

Hemlock woolly adelgid larvae are spread via wind, birds, or infested nursery stock. Then, in its nymph form, the hemlock woolly adelgid becomes immobile and attaches itself to a hemlock tree at the base of the tree’s needles. Once attached, the hemlock woolly adelgid pierces the tree with its mouthparts, feeding off of the tree’s stored starches and ultimately preventing nutrients from flowing from needle to twig. This nutrient deprivation causes infected trees to turn greyish, rather than a healthy dark green, and subsequently lose a substantial portion of needles. Both species of hemlock native to the eastern United States, Carolina hemlocks and Eastern hemlocks, are particularly vulnerable to the hemlock woolly adelgid, which has no native predators in the United States.

In hemlocks in northern areas, death after a hemlock woolly adelgid infestation usually occurs after 4-10 years; however, in Southeastern hemlock populations, death may occur in as little as two years. This difference occurs because prolonged cold spells kill hemlock woolly adelgid, and is reflected by the fact that hemlock woolly adelgid is spreading by 8.1 km/year in the northeast, and 15.6 km/year south of Pennsylvania. In the Southern Appalachians, according to Science Daily, “The pest has the potential to kill most of the region's hemlock trees within the next decade.”

Hemlocks are a “foundation species” in riparian zones in the Southeast. A foundation species plays an integral role in creating and regulating a particular ecosystem. Hemlocks create habitats for salamanders and newts, in addition to shading streams, which provide suitably cool water for native brook trout. Additionally, hemlocks regulate stream flow rates. In a 2014 study, researchers found that “peak streamflow after the largest storm events increased by more than 20 percent," in watersheds with considerable recent hemlock mortality. Simply put, the runoff after storms in areas with high hemlock mortality has increased significantly, which causes bank erosion, flooding, and property damage.

For many kayakers, dead hemlocks create safety concerns. Dead trees can fall into rivers and create fatal entrapment hazards called strainers. What is a strainer? Picture your colander at home as you pour in a pot of spaghetti. The colander holds the spaghetti and lets the water flow through. Now imagine that the colander is a downed tree in the river or strainer, you are a piece of spaghetti, and the water never shuts off. Imagine that you swim into the downed tree and are now stuck to it with your airway below the surface of the water, and again, the water never shuts off. This illustrates the deadly consequences of encountering a strainer on the river, and indeed, from 2015 to present, American Whitewater reports that there have been 12 fatalities from people swimming into strainers, and an additional 24 from people becoming pinned in their boat against the strainer. Many Team PHHAT volunteers are motivated to keep hemlocks healthy in order to help prevent the formation of strainers.

Many more are motivated by the desire to use their kayaking skills to access otherwise inaccessible areas for conservation instead of just for fun. Alex Harvey helped create Team PHHAT after he noticed a large number of hemlocks along the Green river--by his estimate, 1,823 large hemlocks rest along the Upper Green alone. Concerned about the devastation that would occur if all of these hemlocks succumbed to the hemlock woolly adelgid, he reached out to the Hemlock Restoration Initiative [HRI], and found that HRI had been unable to treat the hemlocks along the Green river because the Green river is difficult to access by foot. Harvey proposed an idea to send kayakers equipped with treatment materials into the Green river gorge to treat these otherwise inaccessible trees, and Team PHHAT was born.

Team PHHAT is a collaboration between HRI, American Whitewater, Mountain True, and the North Carolina Wildlife Resource Commission, and, of course, the kayaking volunteers. The Hemlock Restoration Initiative developed the treatment and safety protocols used by Team PHHAT, as well as donating equipment and training volunteers to ensure protocols are followed. American Whitewater provides paddler outreach and volunteer engagement, in addition to donating drybags used by volunteers to safely transport the chemicals used to treat trees. Mountain True’s Green River Keeper, Gray Jernigan, and Water Quality Administrator, Regina Goldkuhl, are active participants in Team PHHAT days, and Mountain True also provides essential outreach and fundraising for the project. The North Carolina Wildlife Resource Commission is the governing body that manages the Green River Gamelands and provides oversight, access, and essential permissions for the project.

Depending on the day, and the section of the river being treated, the volunteers range from highly skilled paddlers to beginner kayakers with a passion for conservation. Sam Muller is Team PHHAT volunteer who helped treat trees in the challenging Green River Narrows and says that “It breaks my heart to see the loss of these trees and the subsequent...changes to the places I love. I saw the event [a Team PHHAT day] as a way to hopefully preserve a place for people to experience the magic of hemlock trees.”

A typical Team PHHAT day starts with a safety talk and a review of treatment protocols, along with a discussion about which areas of the river bank are a priority. The volunteers then split into treatment teams and head to the river, where they paddle to their designated area and begin treating trees, marking each tree’s location on a GPS. A designated lead and “sweep” boat ensure that all treatment teams are accounted for, and treatment teams often pair skilled paddlers with beginners for safety.

To date, Team PHHAT has treated nearly 1,500 trees along the Green river; however, the treatment provides only temporary protection against the hemlock woolly adelgid. Team PHHAT treats hemlocks with CoreTect, a brand name for the insecticide imidacloprid. The CoreTect tablets are buried around the hemlock’s root system. The insecticide is then absorbed by the roots and transported to the crown, where it kills the hemlock woolly adelgid by paralysis. CoreTect provides protection against the parasite for approximately five years, after which the trees will need to be re-treated. Currently, scientists are working towards a long term solution by introducing beetles that prey upon the hemlock woolly adelgid with limited success.

Team PHHAT is able to buy the hemlocks along the Green river valuable time until a long-term solution can be found. To make a donation to support Team PHHAT, visit https://paddlersforhemlocks.com/, and for information about upcoming Team PHHAT treatment days, click here.

Team PHHAT also put together a video for a behind the scenes peek at a treatment day:

[embed]https://youtu.be/rKkbNcCjuG4[/embed]

Cover photo: Team PHHAT volunteers

Comments ()