Winter Warfare in the Colorado Rockies

In the high-stakes tug-of-war between mega-conglomerates Alterra Mountain Company and Vail Resorts, independently-owned ski areas face a tough choice: partner with the big dogs or get creative to stay relevant.

The ski industry’s 2018 pre-season media reel dramatizes the battle royal between Alterra Mountain Company and Vail Resorts in their quest to become Colorado’s undisputed “king-of-the-ski-hill”.

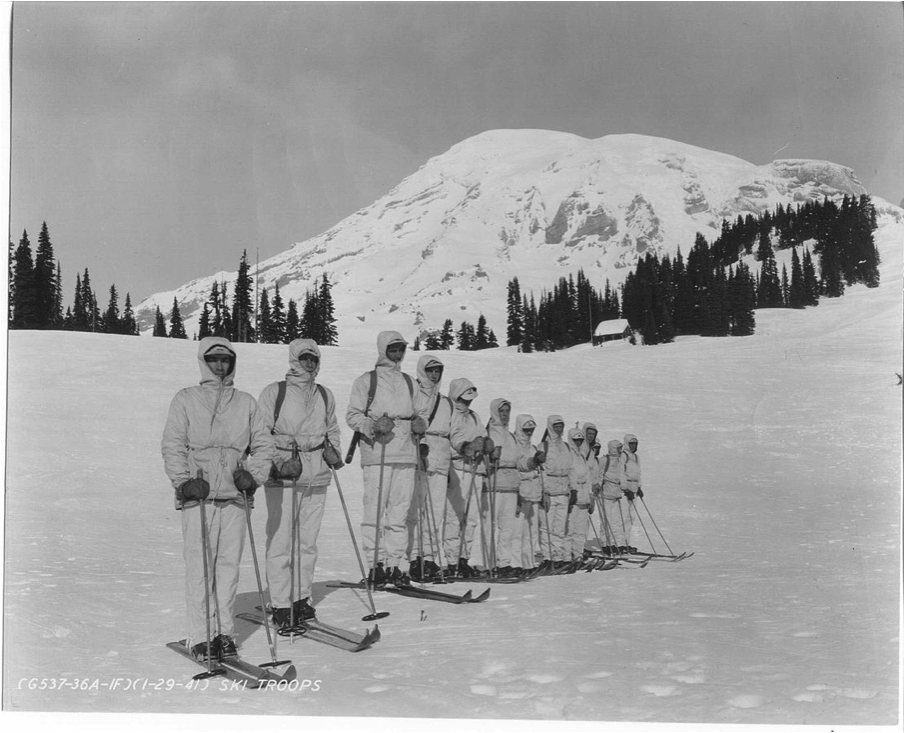

These large corporations hold tenure in a sport where idiosyncrasy is historically celebrated. When gold was discovered in Colorado circa 1859, miners and prospectors used crude skis to cross mountain passes and battle snowdrifts. Those frontiersman and their primitive planks were harbingers of a world-class ski culture; in the early 20th century, Norwegian champion Carl Howelsen brought ski jumping to the western slopes, and later, 10th Mountain Division “Ski Troops” returned from WWII and popularized the sport. Over 175 recreational ski areas have graced the spruced slopes of the state’s jagged Rockies, many of them experiencing rapid stints of boom-or-bust reminiscent of the area’s gold mines.

“Mismanagement, financial issues, inconsistent snowfall, and insufficient clientele"

Local ski hills nucleated mountain communities and provided residents with affordable access to the slopes. These mom-and-pop operations, oftentimes just a single chairlift or towrope, were highly susceptible to both financial hardship and climatological slump. In 2018, Boulder-based adventure production company The Road West Traveled debuted Abandoned, a ski film that explores these now-shuttered destinations. Co-producer Lio Delpiccolo says that many of these spots went under well before today’s conglomerates moved in. “Mismanagement, financial issues, inconsistent snowfall, and insufficient clientele drove many small hills to close their doors,” he informs.

[embed]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c_Lv_HrTRNs[/embed]

The small-scale resorts were not generating staggering profit, but to locals and visitors, they were the sine qua non of old-school mountain culture.

That homespun era has been largely superseded by skiing’s new epoch: The Age of Acquisitions. Just 30 resorts remain in operation statewide, and most of them are owned or managed by a handful of large companies. Ski towns have evolved from humble mining camps to high-end Swanksvilles: main streets packed like Times Square on winter weekends, Starbucks on every corner, and some of the most expensive real estate in the country. The big ski resorts are similarly crowded, the slopes overwhelmed by tourists and the lodges by $15 hamburgers.

Some locals decry the megalomania of corporate operators and commodification of the ski-town experience (and not to mention the nightmare I-70 traffic), but the influx of tourism is a boon to local economies. And the mom-and-pop hills that frequently scraped through each season by the skin of their teeth have found new financial opportunity by way of big-name acquisition. It may be hard to admit, but even as Vail and Alterra glamorize and mass-produce the recreational skiing experience, their sheer might can benefit smaller resorts and actualize projects such as affordable employee housing.

In 2016, pre-season Epic Pass sales netted the company $525 million in cash.

Vail Resorts, today worth a cool $1.4 billion, has been perfecting its acquisition prowess since the early 2000s. With CEO Robert Katz at the helm, the company snatched up big-name resorts like Utah’s Park City in 2014 and Canada’s Whistler Blackcomb and Vermont’s Stowe Mountain in 2016. The multi-national headliners complement classic Colorado destinations like Breckenridge, Keystone, and Vail. The 14-resort gestalt assumed the moniker “Epic Pass” in Vail’s famous industry innovation. A season pass bestows its holders’ keys to all the kingdoms for a ridiculously low price, and every resort added to the repertoire is an opportunity to pull more skiers into Vail’s robust orbit. In 2016, pre-season Epic Pass sales netted the company $525 million in cash. Vail Resorts also draws a portion of its annual revenue of $425 million from hotel and real estate development and guest sales in resort villages.

Alterra Mountain Company, Vail Resort’s upstart rival, is the brainchild of a 2017 joint venture of KSL Capital Partners and Henry Crown & Company. The arrows in their quiver include Colorado’s Steamboat Springs and Winter Park and California’s Squaw Valley and Mammoth Mountain. A total of 26 resorts comprise the “Ikon Pass”, Alterra’s answer to the Epic Pass’s preeminence.

"Ninety percent of our income comes from pure, unadulterated skiing.”

Jen Brill of Silverton Mountain, an independently owned-and-operated resort in the southern San Juans, says that competing with the huge conglomerates is an uphill battle. Vail and Alterra draw from a massive clientele and a diverse revenue stream. “Small family-owned ski areas will struggle to stay relevant in the coming years,” Brill cautioned. “We don’t have other revenues for income like luxury real estate, merchandise, and expensive villages. Ninety percent of our income comes from pure, unadulterated skiing.”

Brill and other local operators don’t benefit from the financial gusto of the top dogs, but they offer an intimacy with their clients that is sacrificed with scale. “Close relationships with our resort guests is key. We see in a year what most of those resorts see in a day. As buyouts have happened, we think Vail will have problems with heavy crowding, and we can draw the crowd that will pay a little extra for solitude and independence,” Brill opined.

“My constant mantra is that the skiing comes first,”

Moreover, some small resorts are teaming up for a shot at the collective-pass market. Monarch Ski Area partnered with 15 other resorts on an affordable pass, and Purgatory owner James Coleman launched a “Power Pass” of five small southwest ski hills with limited days at bigger resorts. Coleman corroborates Brill’s emphasis on the esotericism and individuality of the ski experience. “My constant mantra is that the skiing comes first,” he asserts. “All the lodges and restaurants, those things are all important, but the skiing has got to be first.” He wants to target the drive-up vacationers and local enthusiasts—a smaller but sturdy market that might be repelled by the splashy Vail crowd.

The massive resorts in Vail’s repertoire may draw the most visitors, but the company recognizes the value of homespun charm. They moved to attract the type of skiers that Brill and Coleman are courting via acquisition of community-cherished Crested Butte Ski Resort in 2018. In addition to a partnership with independent Telluride Ski Resort, these hills infuse Vail’s Epic Pass with local flavor. Alterra Mountain Company has secured congruous partnerships with iconic independents Aspen Snowmass and Wyoming’s Jackson Hole. Telluride co-owner Bill Jensen opines that big-name partnerships will become the financial stratagem for locally-held resorts. “I think alliances are going to be just as prominent as acquisitions going forward. These two entities [Vail and Alterra] don’t necessarily have to buy a resort to bring it into their group.” Crested Butte representative Zach Pickett expressed enthusiasm for the impending increase in tourism. “Sharing Crested Butte’s legendary terrain and extraordinary mountain town with new guests is something the resort is very much looking forward to,” he says. “We are confident that our town and mountain charm will remain the same.” Given the perks, will all of Colorado’s in-bounds terrain soon fall under one of two sprawling umbrellas?

There’s an enduring ism that corporations like Vail and Alterra value profit over people. But with limited budgets and resources, small resorts can really benefit from the influx of capital provided by corporate buyout. For example, Vail promised to spend $35 million in improvements over the next two years at recently acquired Crested Butte. And the Epic/Ikon Pass label, be it an allied or acquired destination, ensures a lucrative flow of tourists eager to spend cash on rentals, food, and merchandise. Finally, Vail and Alterra have the monetary fodder to fuel vital community projects. In October, Vail announced plans to develop deed-restricted workforce housing for their arsenal of seasonal employees. The lack of affordable housing in ski towns is a salient crisis in Colorado’s high-county, and ski companies have a vested interest in housing the workers who keep the lifts running and the village coffee brewing. Affordable housing projects are hindered by local zoning laws and soaring home values; Vail’s bottomless capital could support meaningful infrastructure in the ski towns that anchor their resorts.

If momentum is any indication, Vail and Alterra will increasingly dominate the landscape of the Colorado and national recreational ski industry. Independently-owned hills want to retain the high-octane individuality and counter-culture charisma of their origins, but the siren’s call of the Epic/Ikon Pass will continue to define skiing’s future.

The Outdoor Journal has reached out to Alterra Mountain Company and Vail Resorts, but so far they have declined to comment.

Cover Photo: A skier drops a cornice at Silverton Mountain Resort, notorious for its steep terrain. By Zach Dischner via Wikimedia Commons.

Comments ()