Alone Across Antarctica Part 5: The Impossible Truth on Antarctica

A virtually impossible world record crossing on Antarctica is disavowed by polar legends; but who is right in the final analysis?

The Outdoor Journal's 5-part series Alone Across Antarctica began with a breakdown of Colin O’Brady's most recent world record attempt to cross Antarctica on a solo mission with no support and no assistance. In Part 2, Captain Louis Rudd broke down the challenges on his simultaneous 56-day journey. In Part 3, Børge Ousland recounted the first-ever solo crossing of Antarctica in '97 to share his perspective on the latest record-breaking attempts. In Part 4, Mike Horn discussed his long-distance record across the entire continent. In this final installment, The Outdoor Journal dissects each perspective to form a comprehensive conclusion.

On December 26, 2018, American Colin O’Brady completed a 54-day expedition across Antarctica, traversing over 930 miles and culminating in one constant ultramarathon push that covered the final 77 miles in 32 sleepless hours. Hauling a 400-pound sled with all of his food and survival gear, O’Brady faced hurricane-force winds, temperatures below minus 25 degrees Fahrenheit, six foot high snowdrifts and the danger of unseen crevasses.

O’Brady claimed a new world record, “The Impossible First,” to be the first person ever to cross Antarctica alone, with no support and no assistance.

This world record attempt was just the latest in a series of jaw-dropping feats O’Brady has achieved. He’s the fastest to complete the Explorer’s Grand Slam, the Seven Summits, the Three Poles, and the 50 Highest Points of the United States - all of these after suffering a devastating fire accident in Thailand that forced him to learn how to walk again.

According to O’Brady, “I would say the Antarctica crossing, particularly because it's the world's first, is probably my proudest accomplishment.”

The Outdoor Journal interviewed O'Brady to discover the unique challenges that he faced crossing Antarctica. Read Colin O’Brady’s full interview here.

"As humans, we have these reservoirs of untapped potential inside of us and we can achieve such amazing things.”

O'Brady's non-profit Beyond 7/2 is dedicated to empowering children to dream big and lead a healthy lifestyle.

Two days after O’Brady, a British adventurer 16 years his senior who has clocked in over 3,000 miles (4,800 km) on Antarctica over three expeditions, completed the same journey, from the Hercules Inlet to the start of the Ross Ice Shelf. Given Antarctica’s short expedition window, Captain Louis Rudd, the Antarctica veteran, and O’Brady flew in to their starting point on the same Twin Otter aircraft in what would become a race for the record books. Their individual achievements are undeniable - to survive for two months in the harshest environment on the planet - and the mental and physical strength it took to complete their journeys is awe-inspiring.

Over the past two years, another noted polar adventurer failed the attempt when he ran out of food, and tragically, accomplished explorer Henry Worsely died due to complications from the journey.

However, shortly after O’Brady and Rudd flew back to civilization, O’Brady’s “Impossible First” claim came under fire from journalists and other established polar explorers. Under question was whether O’Brady made a true crossing of the continent and also whether his route was truly “unsupported.” Alpine Mag went so far as to call O'Brady's record “Fake News” and even “cheating.” The New York Times ran two pieces, first on the day Colin finished, calling it “one of the great feats in polar history,” and later, a breakdown by David Roberts that discredited the achievement by calling it an arbitrarily defined first, since Børge Ousland had crossed Antarctica in 1997 without resupply.

"His claim is an insult to Børge Ousland, who did the first traverse in 96-97." - Horn

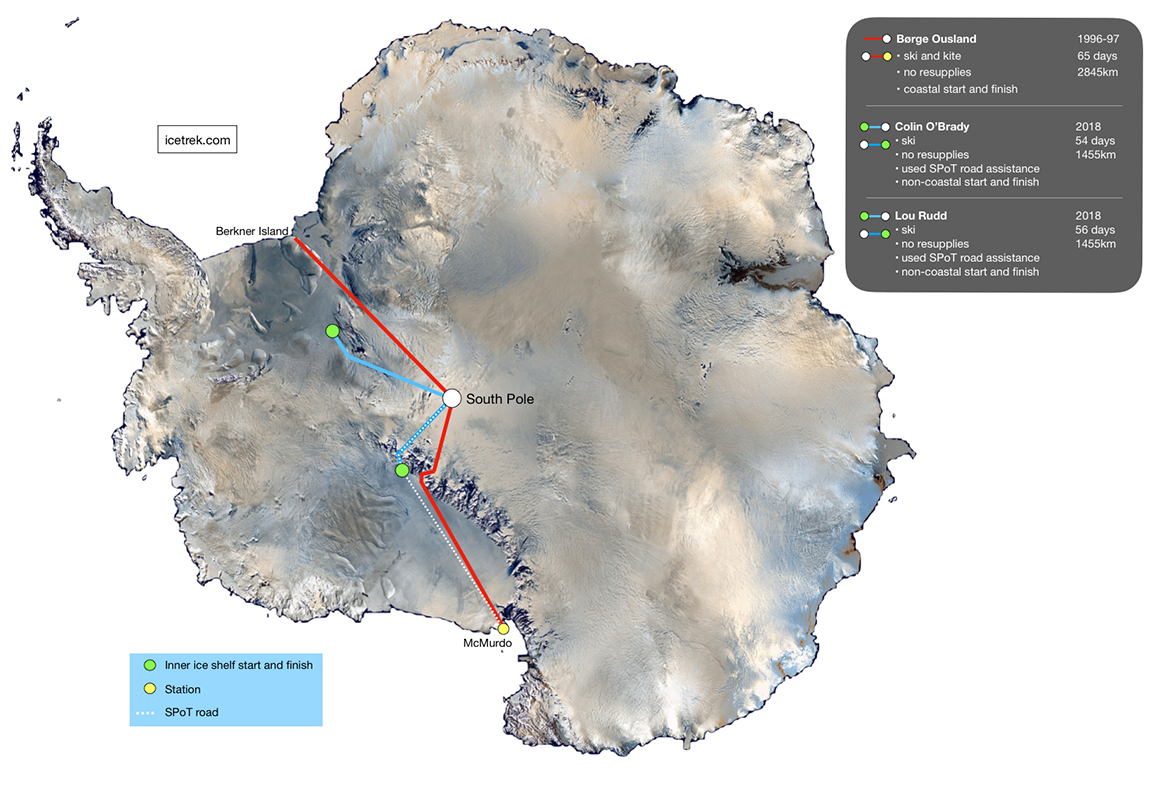

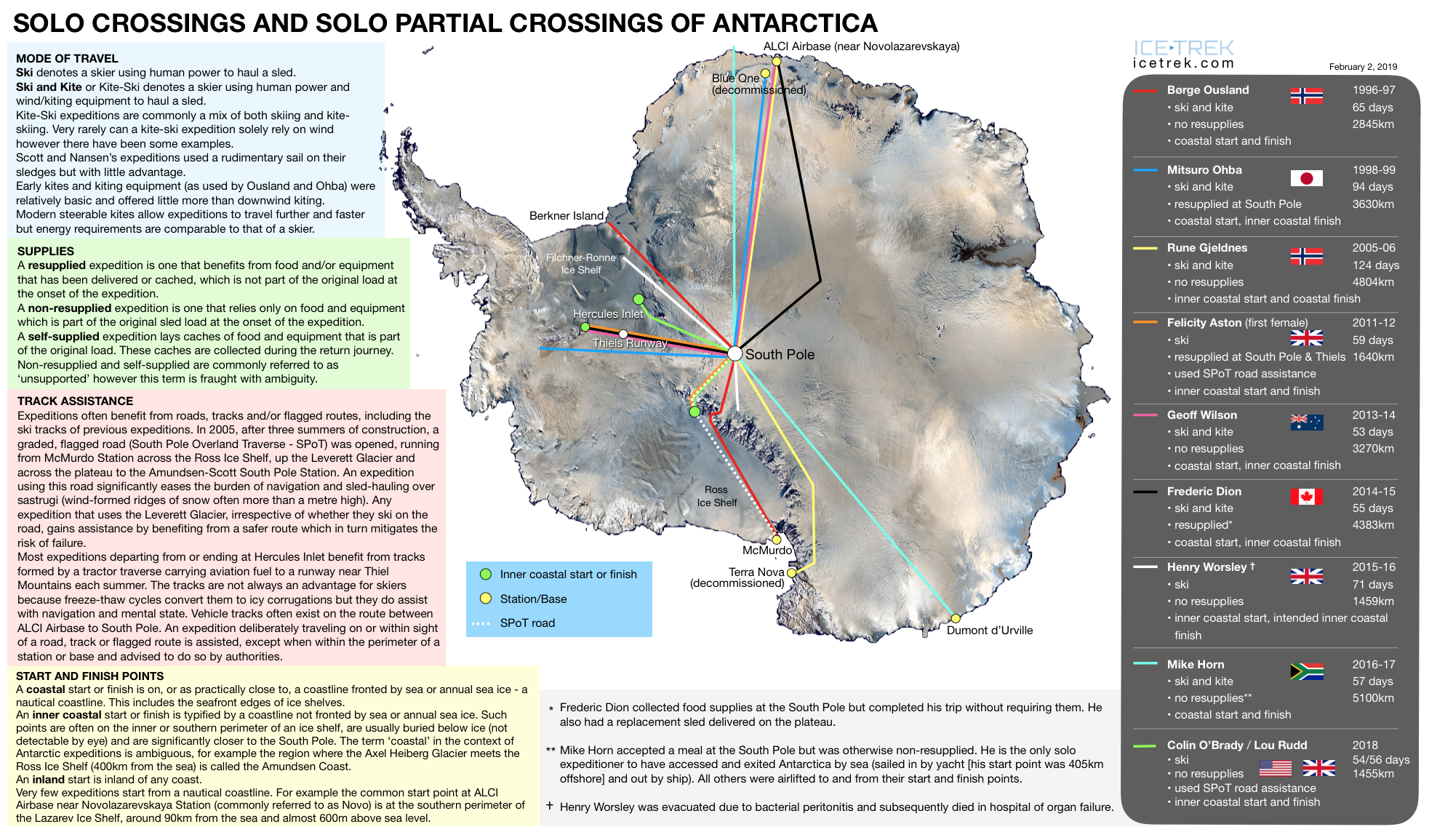

From November 15, 1996, to January 17, 1997, Norwegian legend Børge Ousland made the first solo crossing of Antarctica, covering 1,864 miles (2,845 km) from Berkner Island in the Weddell Sea to McMurdo base on the Ross Sea in 64 days, about twice as far as O’Brady and Rudd. Børge did so alone, and without resupply, but with the aid of a Beringer sail. According to the polar guidelines, Børge's use of the windsail on portions of his journey constitutes “assistance” by the wind. O’Brady covered over 930 miles in 54 days and claims a world first because his journey relied exclusively on his own muscle power.

According to Ousland, “I have great respect for their achievements but I don’t approve and I don’t have any respect for their claims. Ousland put it bluntly, “It's not impossible and it's not the first.” Read the full Børge Ousland interview here.

O’Brady’s world record attempt was not arbitrarily defined. These criteria of “solo,” “unsupported” and “unassisted” are all established classifications in the polar community. By recognizing his record, we're not teetering on a slippery slope for excessively arbitrary firsts like the first solo vegan crossing, or the first solo crossing wearing a too-too. We can examine the polar traverse definition, as well as the meaning of “support” to determine O’Brady’s rightful place in the history books.

DID O’BRADY COMPLETE AN OFFICIAL POLAR TRAVERSE?

"In my philosophy of a crossing, you finish when you have water in front of you.” - Horn

Børge Ousland, who traversed the “White Continent” from coast to coast, took issue with O’Brady and Rudd’s inner-coastal route, which began and ended within the ice shelves. “I never considered going from the bottom of the mountains (like O’Brady and Rudd did). It always stood out to me as a very artificial route because it’s glacier ice, it’s not sea ice. Those ice shelves have been there as long as 100,000 years and that’s longer than those low lying countries like Denmark and Holland. So these ice shelves are ancient and they are part of the inland side.”

Ousland concludes, “Many have done the inland start, and it’s a great way to go to the South Pole, but you can’t claim an Antarctic Crossing.”

Echoing Ousland’s sentiment, legendary adventurer Mike Horn also spoke out in reproach of the O’Brady and Rudd route. “Børge Ousland did the first crossing in 96-97 and O'Brady cannot claim that. Børge did a route with double the distance and weight in his sled, starting on the ice edge and finishing at the ice edge, and that I consider a full crossing of Antarctica. In my philosophy of a crossing, you start on the ocean and finish when you have water in front of you.”

Horn realized his own world record for the longest Antarctica crossing in 2017 without resupply. Docking on the coast with his own ship Pangaea, Horn skied and kited an astounding 3,169 miles across the continent in 57 days. As a throwback to the days of Amundsen, Horn arrived by ship and started his expedition outside the commercial expedition period in spring, when the ice breaks up enough to make a landing, knowing there would be no chance for rescue until he reached the South Pole. Gauging the vast distances he needed to cover each day, Horn adapted his biological clock to a 30-hour day to avoid starving in a desert of snow and ice. Read Mike Horn’s full interview.

According to guidelines set forth by AdventureStats.com:

[su_quote]“An Antarctic traverse has to traverse the full continent. The start and end points have to be from the boundary between land and water - the coastline. Permanent ice is considered part of the ocean, not the land. If the coastline is not obvious due to permanent ice, the start point should be according to the mapped outline of the coast.”[/su_quote]

Applying this guideline to O’Brady’s crossing, he did complete a true Arctic traverse because permanent ice is considered to be part of the ocean. There is only water underneath it. So the Ronne Ice Shelf and the Ross Ice Shelf can be excluded from the route, even if they have existed there for more than 100,000 years.

Ousland disregards these guidelines: “Those guys who made that definition, they did the inland start themselves, and they obviously had a reason for calling that the coast.”

“It's not impossible and it's not the first.” - Ousland

Ousland would agree with journalist David Robert’s assessment of the arbitrary distinctions within O’Brady’s claim to be first. “Then some guys made up their own definitions of doing a traverse that is the first-ever 'unsupported' and 'unassisted,' thinking normal people will never know the difference, then it sounds like you’re the first ever to do it, and that’s actually what’s written in the papers.”

Observing this map of solo crossings, we can see the progression over time of routes from coastal crossings to inland routes that bypass the ice shelves.

The Messner Start

O’Brady and Rudd chose to begin their journey from the “Messner Start” on the Ronne Ice Shelf, which sounds official, co-opting prestige from the legendary Reinhold Messner, but is in itself a misnomer. Messner never intended to start from inside the ice shelf. His original plan was a drop off at Berkner Island (where Børge Ousland started) but a fuel shortage on the Twin Otter plane forced him to relocate, much to his dismay.

An Invisible Finish Line

On the final day of his expedition, O’Brady posted to social media about crossing an invisible finish line. “The wooden post in the background of this picture marks the edge of the Ross Ice Shelf, where Antarctica’s land mass ends and the sea ice begins. As I pulled my sled over this invisible line, I accomplished my goal: to become the first person in history to traverse the continent of Antarctica coast to coast solo, unsupported and unaided.”

https://www.instagram.com/p/Br3V0vCHh0H/

But Ousland considers that invisible line between land-mass and ice shelf to be arbitrary. “When Colin O’Brady came down on the shelf ice he said, “Now I am on sea ice.” But he’s not, he’s on one kilometer thick glacier ice which is part of Antarctica. When you see a real satellite image of Antarctica, then you see the true extent of both ice and land. I have a great respect for their achievements but I don’t approve and I don’t have any respect for their claims.”Just as Messner agonized over his logistical issues on Antarctica, today’s logistical limitations also determined the start and end points for O’Brady and Rudd.

According to Captain Rudd, there is not enough time in the expedition season to traverse both ice shelves without wind assistance. “It wasn’t even an option for me and Colin to start out on the actual ice shelf. We couldn’t do it because there wasn’t enough time available. There are only 90 to 100 days at best in the expedition season.

"I have skied past the whole Ross Ice Shelf, but now it’s just not feasible for a crossing.“ - Rudd

Further, a coastal start was off the table because of safety and insurance issues. “We also couldn’t do it because of the logistics operating now. You’ve got one company ALE (Antarctic Logistics & Expeditions) that does the logistics support, flies you to your start point, provides your emergency cover, and picks you up at the end. For insurance reasons now, with landing the plane in prepared areas, and reach of the aircraft, they don’t give you the option to be able to fly out to the coastline like they did back in the 90’s. Mike Horn got around it via his yacht. He’s a full time adventurer so he’s got his own crew to land him on one side of the continent and pick him up on the far side when he finished the journey. So we went with one of the central points that’s been viewed as the coastline of Antarctica for the last 20 years - the Messner start.”

To Captain Rudd, who has skied across both ice shelves in previous expeditions, the inner-coastal route is the established route of the modern era. “The Ronne Ice Shelf and the Ross Ice Shelf are frozen sea ice, they are giant frozen bays (Ross Ice Shelf is the size of France). In the modern era, everyone says that’s the actual coastline of Antarctica. I’ve done the ice shelves before, back in 2011 before this insurance issue, me and Henry (Worsely) did get dropped off at the Ross Ice Shelf, the Bay of Whales, where Amundsen started. And I have skied past the whole Ross Ice Shelf, but now it’s just not feasible for a crossing.“ Read Captain Rudd’s full interview.

DID O’BRADY RECEIVE SUPPORT?

While the spirit of adventure endures, generational differences abound between today’s modern explorers and the Antarctic heroes of lore, dating back to Roald Amundsen, who became the first man to reach the South Pole in 1911. Amundsen’s party wore seal-skin and fur-skin clothing, fashioned their sleds from American hickory and survived off of their sled-dogs.

Even in the days of Reinhold Messner’s attempt in ‘89, navigation was still by sextant, artificial horizon set mostly by compass. Børge Ousland didn’t even carry a radio on his first traverse attempt in ‘95. In contrast, O’Brady was able to speak with his support team back home every day and even make social media posts.

The day after he broke the record, while recovering in his tent on Antarctica, O’Brady was deferential to the trailblazing adventurers who came before him, posting: “Standing on the shoulders of giants, acknowledging a lot of people that have inspired me over time,” - including Amundsen, Scott, Shackleton, Aston and Ousland.

https://twitter.com/colinobrady/status/1078455980109619200?lang=en

However, like Ousland, Mike Horn also took offence to O’Brady’s claim. “His claim is an insult to Børge Ousland, who did the first traverse in 96-97, and has no legs to stand on. Anybody supporting his claim should do some research to understand what was done in Antarctica in the past.”

Aside from being more connected through technology, the question remains whether O’Brady’s “unsupported” claim measures up to the giants who came before him.

According to AdventureStats.com,

[su_quote]“Support refers to external power aids used for significant speed and load advantage. Typical aids are wind power (kites), animal power (dogs), or engine power (motorized vehicles). Only human-powered expeditions are considered unsupported.”[/su_quote]

“What was different about our journey’s was the style." - Rudd

O’Brady and Rudd studied these rules carefully to ensure their claim met the criteria for “unsupported.” According to Captain Rudd, “What was different about our journeys was the style. We were claiming that we were the first to do it in that particular way - unsupported. No kites. No resupplies. We both researched it to make sure we were 100% correct that nobody had skied across unsupported with no resupply and we were correct in that. What Børge did was an incredibly huge distance. And Mike’s distance was absolutely vast. You could only do those journeys with a kite. It’s as clear and simple as that.”

"You can ski blindfolded there actually." - Ousland

However, the guidelines also state that “Using tracks created by motorized vehicles (same goes for bridges or roads) is considered support.” It’s contended by some that O’Brady’s use of the South Pole Overland Traverse (“SPOT”), a supply track built by the U.S. government in 2005, equates to “support” under the definition because it is marked, and large vehicles frequently access the road, grooming away the sastrugi which would otherwise make skiing more difficult. The SPOT runs from the South Pole to O’Brady’s finish line at the bottom of the Leverett Glacier, over 300 miles, covering the final third of the expedition.

According to Ousland, “It’s supported because you can double the distance on that road and you don't need to worry about navigation. There's a flag for every four hundred meters, and crevasses are filled up, and you can ski blindfolded there actually. There is no danger at all and it's so much easier to ski there than going on the side with sastrugi where you have to navigate yourself. They will never be able to claim that trip as unsupported.”

"Following a track can not be compared with a new route." - Horn

Mike Horn notes the difference between following a track road and forging a new route across an unknown landscape. Horn had no maps or data prior to his traverse of the mountain range in Queen Maud Land, and he carried ice axes, crampons and ropes in case he encountered crevasses. “On frequently used routes like O’Brady took, you cannot avoid tracks and groomed roads. All along his route, he could be rescued and it takes the unknown adventure out of the exploit. Any expedition is a feat and needs courage but following a track can not be compared with a new route.”

It’s a judgment call on whether O’Brady’s human-powered expedition truly meets the standard for “unsupported” or whether the SPOT constitutes “Other Support” by use of aids such as roads, bridges and premade tracks - a difficult call to make without first-hand experience. Neither Ousland nor Horn has skied the South Pole Overland Traverse. And according to both O’Brady and Rudd, the SPOT’s conditions were actually more difficult than their non-track section.

O’Brady describes his experience: “With the way that the wind was blowing, and the drifts and the whiteouts, the rutted up ground on the SPOT in a lot of ways made it even more challenging.”

Captain Rudd selected the SPOT route for safety, not ease, “I skied parallel to the traverse because the vehicles churned it up, it was just rutted, filled with spindrift and it was actually a pretty crappy surface. So this big myth that it’s some flat ice road is complete rubbish. The other thing that was brought up was the little bamboo poles with a flag in it every four hundred meters. They were handy, but I still had my compass on. And by the time I got to that track, I’d previously skied 2,000 miles across Antarctica without bamboo poles and never had a navigation issue, so they didn’t make any difference. I certainly wouldn’t want to use it again, to be honest.”

THE FINAL ANALYSIS

Semantics aside, there's no doubting the sentiment shared by Sir Ranulph Fiennes, one of the world's greatest living explorers, about what O'Brady and Rudd achieved - to have journeyed across the continent alone without a single day's rest "is nothing short of astonishing," a true testament to their mental and physical endurance.

Like their seemingly indestructible sleds, these men must be made of carbon-kevlar construction.

But, in the final analysis, does O’Brady’s claim for the “Impossible First,” the first person to traverse the continent of Antarctica solo, from coast to coast, unaided and unsupported, stand alone in the record books?

O’Brady’s inner-coastal route of 930 miles was about half-that of Børge Ousland’s and did not include the ice shelves, but according to established polar guidelines, the ice caps are distinguished from the Antarctic landmass and are considered part of the ocean. This definition of permanent ice seems counter-intuitive, and any record that has an invisible finish line lends itself to scrutiny. One could argue that permanent ice, like the Ross Ice Shelf and Ronne Ice Shelf, which have existed for over 100,000 years, should be regarded as land.

However, a true coast to coast traverse without the use of a kite appears to be beyond the limits of human capability. Mike Horn traveled 3,169 miles in 57 days with the aid of a kite, that's 2,000 miles more than O'Brady's 54-day human-powered expedition. As O’Brady puts it, “It's a big math equation. How heavy of a sled can you pull for how big of a distance? At a certain weight, your sled would be too heavy in the beginning because you're not getting resupplies so you wouldn’t be able to even move it at all.” Working through the equation, if you double the distance to account for both ice shelves, then you would also need to either double the amount of food and supplies or double the number of miles covered each day. Given that O’Brady and Rudd took zero rest days, hauled their sleds for 12 hours each day, and scrutinized over packing every bit of food and gear down to the gram, an unsupported coast to coast crossing seems like an order of magnitude beyond human-powered limits.

It’s difficult to come to an objective conclusion as to whether the South Pole Overland Traverse, which runs from the Leverett Glacier down to the McMurdo base, disqualifies O’Brady’s “unsupported” claim. Using decades-old aerial photos for navigation, Ousland and Horn were probing unknown landscapes with the real danger of falling into crevasses. In contrast, SPOT significantly reduces the dangers of falling into a crevasse, and its markings make navigation easier; however, it’s unclear whether the track equates to the same level of assistance as wind power or motorized support given the first-hand accounts by O’Brady and Rudd of their difficult goings.

To allege that O’Brady was looking for a shortcut into the record books would be disingenuous. He stands for setting near-impossible goals and pushing himself to the limits of human ability. He seeks out suffering. Over 54 days in Antarctica, he endured a nightless limbo, a frozen desert with no signs of life, hauling his life pod for 12 hours a day up into an altitude of over 9,000 feet. A multiple world record holder, the fastest to reach the North and South Poles and climb Mount Everest, O’Brady is also the kind of sportsman to wait an extra two and a half days for Captain Rudd to finish, despite being almost out of food and exhausted from his 32-hour ultramarathon finish, so that they could fly out together. When asked why, O’Brady said, “To look each other in the eye and acknowledge what we both accomplished.”

The “Impossible First” is in part hyperbole, as part of O’Brady’s media campaign. It’s a catchy marketing slogan to attract attention in today’s ADHD, spin-cycle media landscape. After all, O’Brady crossed the finish line to no fanfare - no ribbon to tear, no crowd to cheer him in, no podium to stand on. Absolutely no one was there. He was all alone, a tiny spec on the White Continent. You can draw out the various routes on a map and measure the distances, but you can’t measure the inspiration and power of belief that O’Brady spreads with his media message. To anyone who has criticized his claim, O’Brady takes the high road, “Regardless of whether people who weren’t out there want to diminish what we've accomplished, for me, I just smile and move on. I know what I accomplished is something that no one in history has ever done.”

Catch-up on the previous instalments of The Outdoor Journal's Antarctica Legends Series 2019:

- Unbreakable: Colin O’Brady Achieves the Impossible Once Again

- For the Love of the Journey: An Interview with Captain Louis Rudd

- Nowhere to Hide on Antarctica: Børge Ousland’s World Record Legacy

- A Race Against Time: Mike Horn on Antarctica

Introducing The Outdoor Voyage

Whilst you’re here, given you believe in our mission, we would love to introduce you to The Outdoor Voyage - our booking platform and an online marketplace which only lists good operators, who care for sustainability, the environment and immersive, authentic experiences. All listed prices are agreed directly with the operator, and we promise that 86% of any money spent ends up supporting the local community that you’re visiting. Click the image below to find out more.

Comments ()