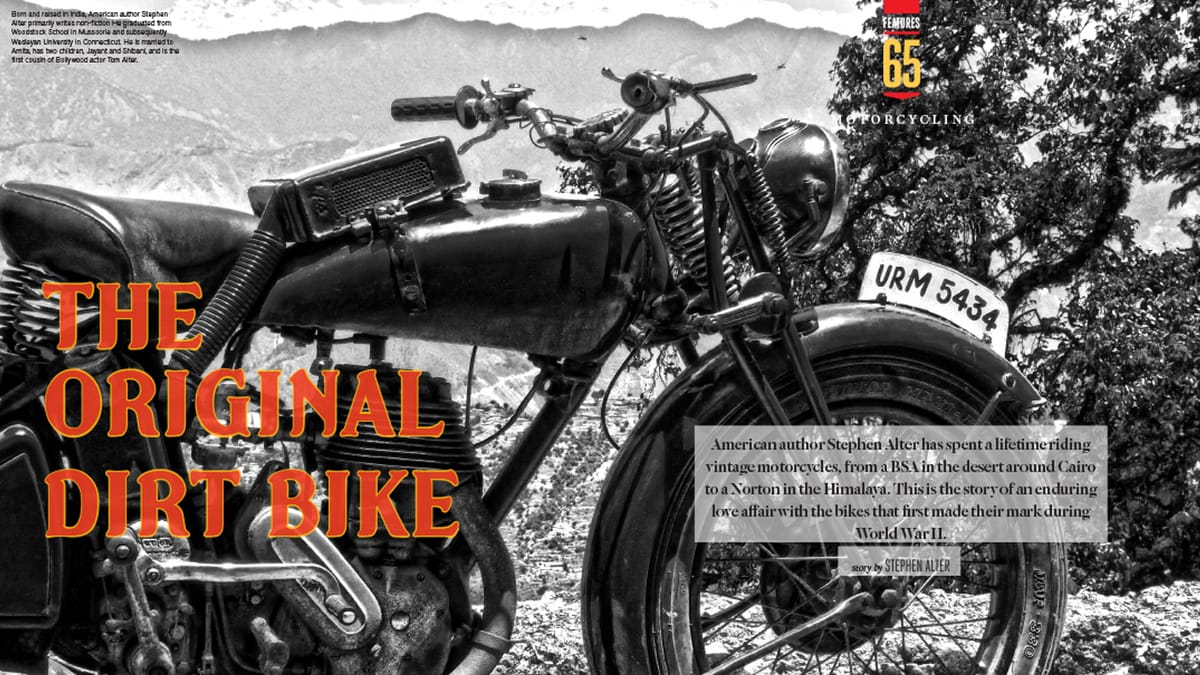

The Original Dirt Bike - Riding a Vintage Norton in the Himalaya

American author Stephen Alter has spent a lifetime riding vintage motorcycles, from a BSA in the desert around Cairo to a Norton in the Himalaya. This is the story of an enduring love affair with the bikes that first made their mark during WWII.

All four fingers on my left hand squeeze the clutch as the heel of my right boot kicks the gearshift into first. The other hand and foot are poised on the brakes, a synchronized choreography of man and machine. With a twist of my wrist on the throttle, the motorcycle responds, defying gravity and altitude, as it makes its way to the top of the hill.

Born to ride in the Himalayas

Our driveway in Mussoorie, 7,000 feet above sea level in the Indian Himalayas, is a good test of the pulling power and resilience of any vehicle, though recently it has become a little easier, now that the steepest sections have been paved. Most drivers surrender before attempting this route. But my 1936 Norton 16H takes the acute angle of ascent without complaint. It has the torque of a tractor and its center of gravity is low enough to keep us from bouncing around on the ruts. Antique car rallies often include a “hill climb” but when you live in the Himalayas, this becomes a daily routine. Born and raised in these mountains, this is where I learned how to drive. It’s one thing to maneuver a 75 year old bike on a flat city road or an open highway but an entirely different matter to negotiate hairpin bends and gravel inclines of 60 degrees. The Norton 16H is designed for rough terrain, the original dirt bike with a proud legacy going back to World War II.

It’s almost as if they were designed to leak oil, with dripping gaskets and bleeding crankcases.

It’s a true growler, especially going uphill, yet reaching the top of the climb, the 500 cc side-valve engine settles into the slow, steady beat of a classic single piston thumper. They don’t make motorcycles like this anymore. Even the so-called retro-models are as revved up and complicated as an iPad overloaded with apps. By comparison, my Norton is like a manual typewriter, a simple piece of machinery that gets the job done.These days most off-road bikes are equipped with stabilized shock absorbers and hydraulic dampers cushioning the rear suspension, which take most of the punishment. Certain models even offer heated hand grips for winter driving. On a Norton 16H, the only allowance for a driver’s comfort are two stiff springs under the saddle – an unforgiving “hard tail” with rigid girder front forks. If nothing else, it creates a greater connectivity with the road, and not the digital kind.

Nothing is ever hopeless; everything can be fixed

Both my father and my grandfather loved road trips, along with the vehicles that made these journeys possible. In 1916, my grandparents first came to India as American missionaries and our family has lived here ever since. Long before I was born, they toured the subcontinent in a Model A Ford, from the Northwest Frontier to the borders of Bengal. Though I failed to inherit their theological persuasion, I still carry my forefather’s love of engines in my genes. At sixteen, I learned to drive on the precipitous hill roads of Mussoorie, behind the wheel of my father’s 1952 Willys Jeep, which he bought from an army disposal auctioneer in Delhi. The only way it started was with a crank and among the many important lessons I learned from my father was that “nothing is ever hopeless; everything can be fixed.” One of the first driving skills he taught me was how to start on a steep hill without a handbrake, placing your toe on the footbrake and your heel on the accelerator, as you let out the clutch. From my mother I learned to carry a good book wherever you go, to read while you wait for repairs to be done. I suppose these are the reasons I became a travel writer.

Once, when the cylinder-head on a Norton exploded because of overheating, the British dispatch rider took a block of teak and bolted it on top. His ingenuity got him safely back to his barracks

My romance with motorcycles began soon after my first novel, Neglected Lives, was sold in 1977. Immediately I squandered the entire advance of 500 pounds sterling on a new Royal Enfield Bullet. A subsequent obsession with WW II bikes started when my family and I lived in Egypt for seven years in the 1980s, while I was teaching writing at the American University in Cairo. During the Second World War, Cairo was headquarters for the Allied Forces in North Africa and stockpiles of arms and vehicles were stored here. A good friend and guru, David Mize, who taught at AUC and spent most of his life in the Middle East, was an antique automobile enthusiast with a predilection for Fords and Bugattis. One day, he mentioned that there was a mechanic in Shubra, one of Cairo’s most congested neighborhoods, who had a warehouse full of old motorcycles. We drove into a maze of streets until we came to a brick wall with a small door in the center.

An elderly Egyptian holding a spanner in one hand and grease on his galabeya, the loose garment he wore, was changing the rear tyre on a beatup Suzuki. He spoke no English and my Arabic was barely sufficient to order coffee. David could converse in Egyptian colloquial but eventually they settled on speaking in French because both of their accents were equally bad, which made the language mutually intelligible. After a lot of vehicular palaver, we were admitted to the inner sanctum of the workshop, as dark and cluttered as a pharaoh’s tomb. The bikes, which had been stored there since the end of the war, had been salvaged from an army warehouse. They were stacked together so closely, I had to climb over top, until I found the one I wanted – a BSA M20, with a single cylinder half-liter engine, just like the Norton I have now. While the two bikes are similar, they are not clones of each other, with unique styling and distinctive features. But both share a reputation for dependability. When I was growing up in India, the BSA M20 was a favorite of circus daredevils, who would ride them around inside a spherical steel cage called the globe of death. As a boy, I remember watching with fascination, as the driver picked up speed going around and around until he defied gravity, turning upside down.

Detour in the desert

A murky green colour, my BSA in Cairo spewed black smoke every time it started, but I fell in love with that bike from the first time I rode it. The mechanic in Shubra got it working, in a manner of speaking, though he didn’t bother with the niceties of tuning or servicing. Fortunately, driving it from downtown Cairo to where we lived in the suburb of Ma’adi, south of Cairo, the tyres didn’t go completely flat and the wheezy piston produced enough compression to get me home. After that it took two years of tinkering and cajoling mechanics to fix the ill-effects of old age and neglect. It always started, even if I had to kick it a dozen times.Four of us, including David Mize, used to go for drives on our BSAs in the desert around Cairo, reliving the glories of the North African campaign. Another friend, who made the mistake of riding pillion - the rear seat has even less cushioning than the front - remarked uncharitably that the only reason the British were able to defeat the Germans in the battle of Al Alamein was because they couldn’t get their motorcycles started fast enough to retreat.

Old British bikes take a lot of patience to drive and maintain. It’s almost as if they were designed to leak oil, with dripping gaskets and bleeding crankcases. The other thing the Brits are famous for is designing a different sized nut or bolt for every part of the bike, so you need an assortment of at least 24 wrenches to take it apart. And, of course, they’re not metric but Whitworth, a different caliber of wrench. When I finally left Egypt in 1995, with my wife Ameeta and our children, Jayant and Shibani, to take up a teaching position at MIT in Boston, the last thing I sold was my BSA. It wasn’t an easy decision but the paperwork to take it out of the country was as complicated as trying to export Tutankhamen’s treasures. Waving goodbye to the young man who bought it, I felt a sharp pang of regret, listening to the receding beat of its engine for the last time. As a memento, I kept a link from the chain, which still sits on my desk today.

Zen on two wheels

even half an hour’s spin on hill roads leaves me with a sore back and rattled bones. Until I’ve had a beer to toast our excursion, my arms and legs tremble with residual vibrations.

For the next ten years, because I was living in America, the land of strict emission controls and prohibitive insurance policies, I stayed away from motorcycles. Harleys never really captured my imagination, though I always coveted an Indian Chief, the ultimate native American bike, which went out of production in 1953. When we left Boston and the MIT and came back to India in 2004, after I said farewell to academia and returning to writing full time, one of the first people I visited was a mechanic named Chaudhury. He had a workshop in Dehradun, thirty kilometers from Mussoorie at the foot of the hill. Back in the ’70s and ’80s, Chaudhury had kept my first bike running. From time to time, old motorcycles found their way into his workshop. Chaudhury had a reputation for knowing how to repair vintage bikes. Earlier during that time, whenever I went to have my first Enfiled serviced, I would longingly eye the 1950s slope single 600 cc Panther that sat in one corner of his garage. It was a rare British motorcycle designed primarily for use with a sidecar. The owner, from Bijnor, had no papersand was asking Rs. 15,000 (about $250), which was more than I could affordin those days. There was also a Sunbeam, another classic British bike, which had a boxy two cylinder engine and looked like a sleek road roller. But by the time I came back to India those bikes were long gone. Having prematurely cashed in my retirement fund, I had some money to burn. Chaudhury shook his head sadly and said he had nothing but a couple of old Bullets and a Yezdi without an engine… then, he hesitated… but of course, what about that? He pointed to a heap of rusted parts, old mufflers and leg guards, bald tyres and a couple of scooters which had been deconstructed beyond repair. Under all of this, lay the skeleton of a bike. As I began to remove the junk from around it, my excitement was growing. It was clearly WW II vintage, like my BSA in Cairo, but when I was finally able to dig it out, the Norton emblem made my heart jump.

Motorcycle diaries

Only a few days before, I’d watched the film Motorcycle Diaries, in which Che Guevara takes a road trip around South America with a friend in 1952, before he became a Communist icon. The bike that they rode was a 1939 civilian model of the Norton 16H, which they named “La Poderosa,” or the Mighty One. I could still see scenes of them pushing it through the mud, as the orchestral soundtrack swelled to the drumbeat of its engine. Before the Norton had been completely excavated from the debris in Chaudhury’s workshop, I had already tucked a generous advance in his hands. Retirement be damned, I was going to ride this bike into the sunset. Never mind that there was more rust than paint and the nuts and bolts looked as if they were welded in place. It had no seat, except for a gnarly tangle of springs. Instead of two tyres, it stood on its rims. But she was more beautiful than any piece of machinery I’d ever seen. It took almost a year for Chaudhury to restore my Norton. I tracked down missing parts in different places, a magneto and carburetor from Chor Bazaar in Mumbai and a new set of valves and a piston from the gullies of Karol Bagh in West Delhi. Finally, she was running.

In the strict caste system of the British Army, officers were issued Triumphs and Ariels, or maybe a Matchless or Enfield, most of which had effete 350 cc engines with overhead valves, which meant they had quicker pickup and ran more smoothly. Certainly, a better bike to escape the front lines under fire. By contrast, sergeants and enlisted men were given BSAs and Nortons, true working class bikes that took the brunt of the war. Hundreds of thousands of these machines were manufactured in the late thirties and early forties. World War II, more than any other global conflict, employed motorcycles as a strategic vehicle and many of the classic motorcycles, such as the legendary American bikes, Indian Chiefs and Harley Davidsons, or the German BSA, proved their value on the battlefields of Europe and Asia. My Norton is a “colonial model” from 1936, just before the war began, equipped with an extra-large air filter mounted on the petrol tank and a heavy iron shield under the crank case, both of which were necessary for navigating unpaved roads across the Libyan desert or through rough jungles near the Burma front. Heroic war stories celebrate these indomitable bikes. Once, when the cylinder-head on a Norton exploded because of overheating, the British dispatch rider took a block of teak and bolted it on top. His ingenuity got him safely back to his barracks, just before the wood went up in flames.

Kick starting a mid-life crisis

Though Choudhury claimed he once drove the Norton all the way to Gangotri, the source of the Ganges, I haven’t taken it on any long drives. It isn’t a touring bike and even half an hour’s spin on hill roads leaves me with a sore back and rattled bones. Until I’ve had a beer to toast our excursion, my arms and legs tremble with residual vibrations. Here in Mussoorie, my friends all drive Royal Enfield Bulletsor Harleys. I salute their preference, for every motorcyclist must find the right bike to match his or her temperament and style, but for me there’s a certain anachronistic pleasure in driving a motorcycle that’s exceeded its expiry date. With most bikes today, you just press a button and it starts. Meanwhile, I tug on the choke, tickle the carburetor, adjust the manual advance/retard lever, before decompressing the engine so the kick start won’t lash back and pop my knee out of joint. Then I take a deep breath and give it a smooth, easy nudge of my boot, like stepping into quicksand. There’s nothing more satisfying than the responsive rumble of internal combustion, a tiny electric spark setting alight the fuel vapours which gets the piston pumping. All of a sudden, the dead weight of more than 200 kilos of steel comes to life.

I head up our driveway with a slow, pulsing roar, no more than half throttle. Then I circle the chukkar road at the top of the hill, breathing in the resinous fragrance of deodar needles on the breeze. To the north the snow peaks of the high Himalayas gleam in the crisp October air. My Norton leans into the corners and its rigid suspension holds the rough road as securely as any new Japanese bike. Back in the seventies, Robert M. Prisig’s Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance created a cult following but this bike leads the way on less travelled trails. Riding a Norton 16H, one feels both the weight of history as well as what Milan Kundera once called, “the unbearable lightness of being.”

Comments ()