Alone Across Antarctica Part 3: Nowhere to Hide - Børge Ousland's World Record Legacy

Norwegian legend Børge Ousland, who navigated unknown landscapes in 1997 to become the first person ever to cross Antarctica alone, has a message for would-be record breakers.

In a 5-part series Alone Across Antarctica, The Outdoor Journal connected with the greatest living polar explorers to discuss their solo missions across Antarctica, the most inhospitable environment on the planet. In Part 1, Colin O’Brady detailed his most recent world record attempt. In Part 2, Captain Louis Rudd explained what it took to survive his simultaneous 56-day journey. In this installment, Børge Ousland recounts the first-ever solo crossing of Antarctica and shares his perspective on the latest record-breaking attempts.

Børge Ousland is a Norwegian explorer and adventurer, among the best who have ever lived. As the first person ever to cross both poles on solo expeditions, Børge is a leading expert on polar exploration.

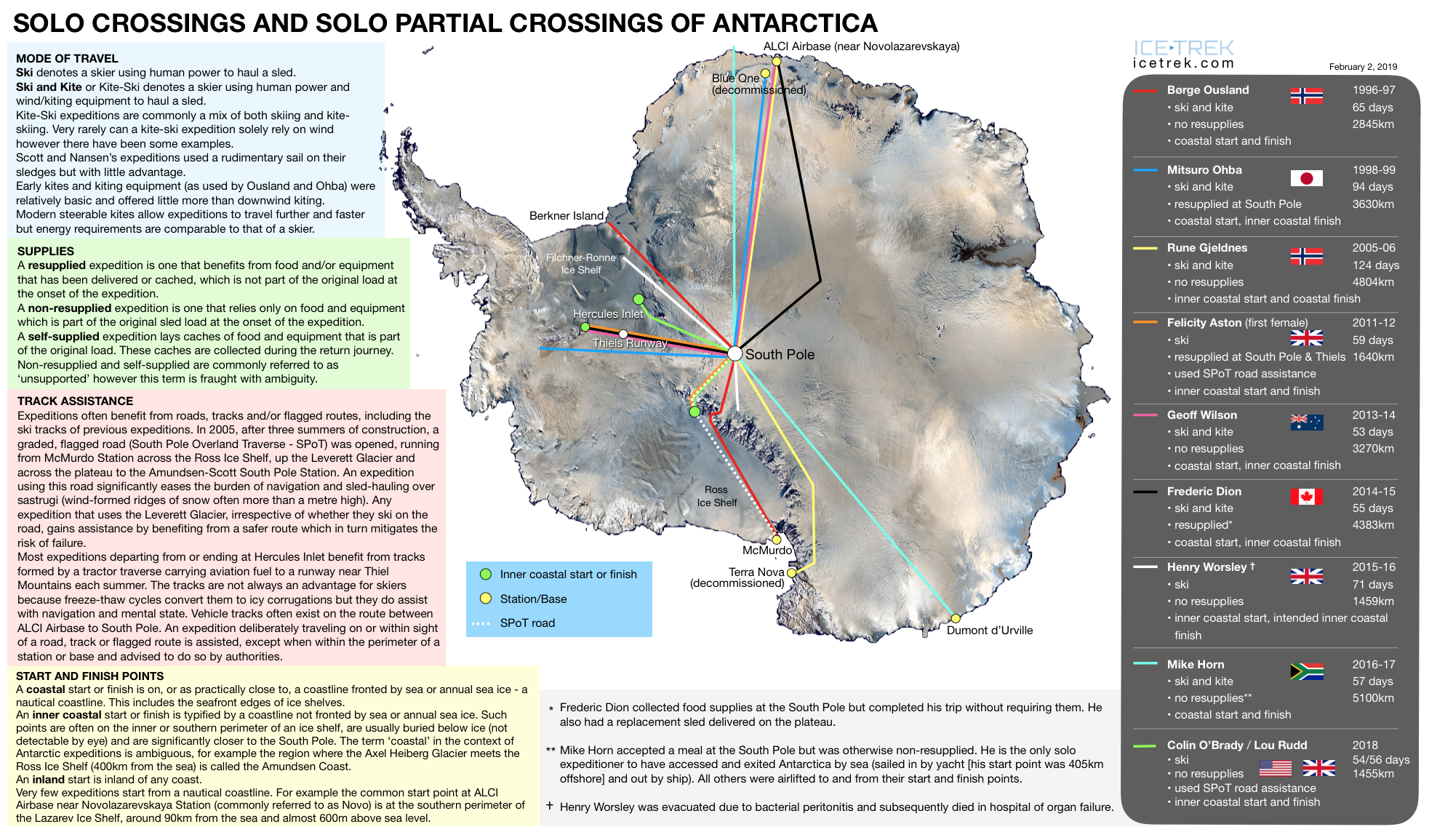

Børge became the first man to complete a solo and unaided journey to the North Pole in 1994. Then in 1997, he made the first solo and unaided crossing of Antarctica from coast to coast, covering 1,864 miles (2,845 km) from the edge of the Ronne Ice Shelf to the edge of the Ross Ice Shelf. In his world-first solo crossing of Antarctica, Børge set out from Berkner Island in the Weddell Sea and reached the McMurdo base by the Ross Sea 64 days later, hauling a 390 pound (178-kg) sled. He used a windsail to help propel him on parts of the journey.

Børge is so dedicated to polar exploration that he even held his wedding ceremony at the North Pole in 2012, flying in guests via helicopter.

The Outdoor Journal connected with Børge to discuss his solo crossing of Antarctica, a world’s first, and how the latest record attempts by Colin O’Brady and Captain Louis Rudd stack up in the history of polar adventure.

WORLD’S FIRST SOLO CROSSING OF ANTARCTICA

TOJ: What initially inspired you to attempt the first solo crossing of Antarctica?

“We all have that need to overcome something difficult in life.”

Børge Ousland: That trip was up for grabs back in the day. I had skied across Greenland. I skied solo to the North Pole in ‘94, that was my big test. In polar conditions, you're up there in the elements fighting yourself, overcoming difficulties and problems, and it's just you, and you have to find these solutions and answers. And that's fascinating for me. But the bottom line - the platform I've built my expeditions on - is adventure. I always liked the outdoors. I like to ski, I like to sleep in tents, I like to be physical, to move around, and be in the "here and now" in nature.

The good part with the expeditions is that you are here and now. You focus on the weather, the equipment, the progress and not something that is going to happen tomorrow, which is more or less what we're doing in daily life.

It's also fascinating to look at something that nobody has done before and think, “Maybe I can do that.” Then you start to think about it and then finally you get that belief in yourself that, “Yes, I can do that!” And then you make it into a plan and you go. So it’s not about being first or greatest, it’s about overcoming something. I think we all have that need to overcome something difficult and get those victories in life.

This project is not just a trip starting from when you put your skis on. It's one year of preparation and it's the whole package, which fascinates me. It actually took me two years to do it. I went there in ‘95 but suffered blisters and frostbite, which got infected, because my gear was not windproof enough. After skiing solo and unaided only to the South Pole on that trip, I still thought I could do it, so I spent another year arranging sponsorship, training, pulling rubber tires, optimizing my equipment, and then I went again in ‘96 and I made it.

TOJ: Some of the explorers that inspired you were Amundsen and Nansen, who worked in teams. What drew you to take that extra step to go for a solo journey?

“Going solo is a mental experiment, it’s inner travel.”

Børge Ousland: In ‘93 I was on an expedition with my friend and we got separated in a whiteout. I wondered how it would be to be out there just by myself. So that’s how I first got the idea to go solo. Before I started on my solo trip to the North Pole in ‘94, I had never spent one night alone in a tent. I think that was a big mental leap. For me, going solo is mostly interesting from a mental and philosophical point of view. Physically, it’s more heavy to go solo because with a partner, you can share the tents and the common equipment, but overall it’s more or less the same. Going solo is a mental experiment, it’s inner travel. It’s hard because you can’t share the memories and joke with your partners but on the other hand you have a totally different dialogue with nature and yourself because there is no one to lean on.

TOJ: Before a trip, is there any way to replicate or train for that sense of isolation?

“When the helicopter left me on Antarctica, I never felt so small in my whole life.”

Børge Ousland: I don't think so. Actually, I did go to a sport psychologist who helps athletes win gold medals in the Olympics. I got a little bit fed up with him because he was just asking questions while I wanted to hear tangible tips on how to make it. But he understood that the point of asking all these questions was actually the right recipe because the whole deal was to make me get to know myself better, because on the South or the North Pole, there is nowhere to hide. You meet yourself. Good sides and bad sides. Feeling alone, or afraid of not succeeding, those feelings will come. If you accept that these feelings are a part of yourself, you’re in a better position to deal with them. So the answer is in yourself. But nothing could prepare me for when the helicopter left me there on Cape Arctichesky on my first solo trip. I never felt so small in my whole life.

A TRUE COAST TO COAST ROUTE

TOJ: Can you explain the process of selecting your route from Berkner to McMurdo, and the difference between your route and the one selected by O’Brady and Rudd?

“On the South Pole, there is nowhere to hide. You meet yourself. Good sides and bad sides.”

Børge Ousland: I planned my route based on aerial photos taken by the US Navy back in the 1950’s and 60’s. I just had a little copy of the images from that era with me and my map was 1 to 250,000 so I was just probing unknown landscapes down there.

I never considered going from the bottom of the mountains (like O’Brady and Rudd did). It always stood out to me as a very artificial route because it’s glacier ice, it’s not sea ice. Those ice shelves have been there as long as 100,000 years and that’s longer than those low lying countries like Denmark and Holland. So these ice shelves are ancient and they are part of the inland side. It doesn’t matter if you take away the ice and there is water underneath, which was found out later. I wanted to go from sea to sea. Berkner had been established by a couple other expeditions before. And I knew that it was possible to get out from McMurdo. So I paid a ticket for a cabin on a cruise ship, for several thousand dollars, that would leave from McMurdo in perfect timing with my expedition.

TOJ: Some of the more recent expeditions like Ben Saunders, Henry Worsely, and now Colin O’Brady and Captain Louis Rudd have chosen the inland start on a route that is about half as long as yours. Do you feel like this modern route is a legitimate crossing of Antarctica?

“Many have done the inland start, but you can’t claim an Antarctic Crossing.”

Børge Ousland: It’s a great trip, but it’s not going from coast to coast. Many have done the inland start, and it’s a great way to go to the South Pole, but you can’t claim an Antarctic crossing. You can see it more clearly when you look at a map. They are deleting the shelf ice from the map when they draw it, it looks like ocean. When Colin O’Brady came down on the shelf ice he said, “Now I am on sea ice.” But he’s not, he’s on one-kilometer thick glacier ice which is part of Antarctica. When you see a real satellite image of Antarctica, then you see the true extent of both ice and land. I have a great respect for their achievements but I don’t approve and I don’t have any respect for their claims.

TOJ: I tried to research the official guidelines for what constitutes a polar crossing and I found one source which is Adventurestats.com which said, “The start point has to be from a boundary between land and water - the coastline. Permanent ice is considered part of the ocean, not the land.” Which is kind of confusing to me. It seems like it should be the opposite. What is the source for the official guidelines for polar records?

“So it's not impossible and it's not the first.”

Børge Ousland: Those guys who made that definition, they did the inland start themselves, and they obviously had a reason for calling that the coast. So those things will be changed in the future. This isn’t something that’s just come up now. I’ve been fighting this battle for over 20 years. I think it was Ranulph Fiennes who was first to call the bottom of the mountains the coast, but his partner Mike Stroud disagreed with that. They were not able to make it all the way to McMurdo and they were totally wasted, so they stopped at the bottom of the mountains and said, “Well, let’s call this the coast and we can claim to be the first unsupported crossing.” And it’s been a controversy ever since. But it’s very good that social media has caused all this interest because people suddenly start to think about it with transparency and finally we can do something about it.

TOJ: One of the things I've been trying to make sense of is the “Messner start” because as I research it, I found out that it was not the point that Reinhold Messner was trying to start from, but it was an alternate start point based on a logistics issue with the plane. So is it a misnomer to call that the “Messner start?”

Børge Ousland: Reinhold Messner, he wanted to start from the coast. The guys who flew him had some logistical problems. That was a big issue. He wanted to sue them. He got so delayed so there was no other alternative than starting from where he started. But he definitely did not call that the coast.

TOJ: I read that he was actually furious that he was forced to change his plans.

Børge Ousland: Yeah he was, big time. I think they paid back some money to close the case. So it's not impossible and it's not the first.

WHAT CONSTITUTES “ASSISTANCE?”

TOJ: One of the other guidelines on Adventurestats.com says that using tracks created by a motorized vehicle is considered support and it seems like the South Pole Overland Traverse (SPOT) might constitute tracks created by motor vehicles because the big trucks groom the traverse. If that is the case, would that take away O’Brady and Rudd’s “unsupported” claim?

Børge Ousland: Sure it’s support because you can double the distance on that road and you don't need to worry about navigation. There's a flag every four-hundred meters, and crevasses are filled up, and you can ski blindfolded there actually. There is no danger at all and it's so much easier to ski there than going on the side with sastrugi where you have to navigate yourself. They will never be able to claim that trip as unsupported.

TOJ: Do the official definitions of "support" and "assistance" make sense to you?

Børge Ousland: They want to change that now. It's still in early parts of the discussion, but they wanted to change it to “assisted” or “unassisted” only, then if you have a sail or you have dogs or whatever, that's just a method of transportation that will be noted under the expedition. So either you’re first or you’re not first, and whatever comes after is just a different way of doing it.

TOJ: O’Brady and Rudd are trying to make a distinction between other solo expeditions like yourself and Mike Horn by saying that you used the assistance of wind power, and that's why they're saying it's a first because they didn't use any device aside from human power.

“On the first trip to the South Pole in ‘95... I didn’t even have a radio.”

Børge Ousland: For me, the bottom line for being supported or not is if you have some outside help. It’s between being totally self-reliant or not. And then method of transportation is secondary. Because you could always walk instead of ski. Is ski “support?” If you stand on top of a hill, and you let yourself go, you will move forward if you have a ski. It’s just about using the techniques that are available to you to move forward. I never considered that using a ski sail, which I did on parts of the trip, would be a controversy in the future. I couldn’t use it on the way to the South Pole because of the headwinds and I couldn’t use it in other parts because of the sastrugi. Then some guys made up their own definitions of doing a traverse that is the first-ever “unsupported” and “unassisted,” thinking normal people will never know the difference, then it sounds like you’re the first ever to do it, and that’s actually what’s written in the papers.

TOJ: O’Brady and Rudd covered over 900 miles. Do you know what percentage of that was on the SPOT groomed road?

Børge Ousland: As far as I know, it’s half the trip.

I think the main thing for me is to get the truth out and I think these guys did great trips and I fully respect their achievements both in the distance and experience they had, but I’m not approving the claiming of first solo crossing and unassisted. That will never happen that I will agree with that.

TOJ: Do you think that there are some still possible first ascents out there?

Børge Ousland: Yeah, there is: to cross the North Pole solo and unassisted. Because I crossed the North Pole solo but I had to resupply because my sled broke. So that's still up for grabs.

SOCIAL MEDIA IMPACT

TOJ: One of the benefits of social media is it allows you to stay in touch with people who care about your journey and also your friends and family. I'm wondering, have you ever looked back and wished that you had social media on one of your earlier expeditions, so you'd be able to stay in touch with people and they'll be able to track your progress, or do you think that that takes away from the isolation element of any adventure?

Børge Ousland: I’m still doing expeditions for the IceLegacy Project, which I do with Vincent Colliard from France, and every night in the tent we have one to two hours of office work (laughs). I think back on my big solo trips when I didn’t have a sattelite phone, and actually on the first trip to the South Pole in ‘95 when I didn’t even have a radio. I was just by myself for two months. Absolutely no outside contact. I think it was good just to be there with nature and concentrating on my journey and myself.

A LASTING LEGACY

TOJ: Can you describe the origin of the concept behind the Legacy Project and the significance of it on a global scale?

Børge Ousland: It is a very important project. It came about after I circumnavigated the Arctic in 2010. Me and a few friends sailed around the Arctic in a trimaran in four months through the northeast and northwest passage. Those areas used to be clogged with ice and it took six years to do it just a few decades ago. It really shocked me how much the ice had retreated in the Arctic. That’s what sparked this idea to cross the 20 greatest glaciers on Earth, to show what is happening with them, because almost all the glaciers in the world are retreating, contributing to sea-level rise. We want to document and tell the story of what’s happening. Our role is creating awareness as eyewitnesses. And secondly, we have two goals, we want to inspire people to get out in nature, that’s the best way to preserve it. And we’ve done nine glaciers now. Read more about the Legacy Project.

Learn more about Borge Ousland on his website. www.ousland.no/

Instagram: @borgeousland

Facebook: @borgeousland

Stay tuned to The Outdoor Journal for the next installment of our Alone Across Antarctica series.

- Monday 8th July: Introducing Alone Across Antarctica Series 2019

- Wednesday 10th: Unbreakable Colin O’Brady Achieves the Impossible Once Again

- Monday 15th: For the Love of the Journey: An Interview with Captain Louis Rudd

- Wednesday 17th: Nowhere to Hide on Antarctica: Børge Ousland’s World Record Legacy

- Monday 22nd: Mike Horn's Race Against Time

- Wednesday 24th: The Impossible Truth on Antarctica

Introducing The Outdoor Voyage

Whilst you’re here, given you believe in our mission, we would love to introduce you to The Outdoor Voyage - our booking platform and an online marketplace which only lists good operators, who care for sustainability, the environment and immersive, authentic experiences. All listed prices are agreed directly with the operator, and we promise that 86% of any money spent ends up supporting the local community that you’re visiting. Click the image below to find out more.

Comments ()