Full Throttle on Siberia’s ‘Road of Bones’

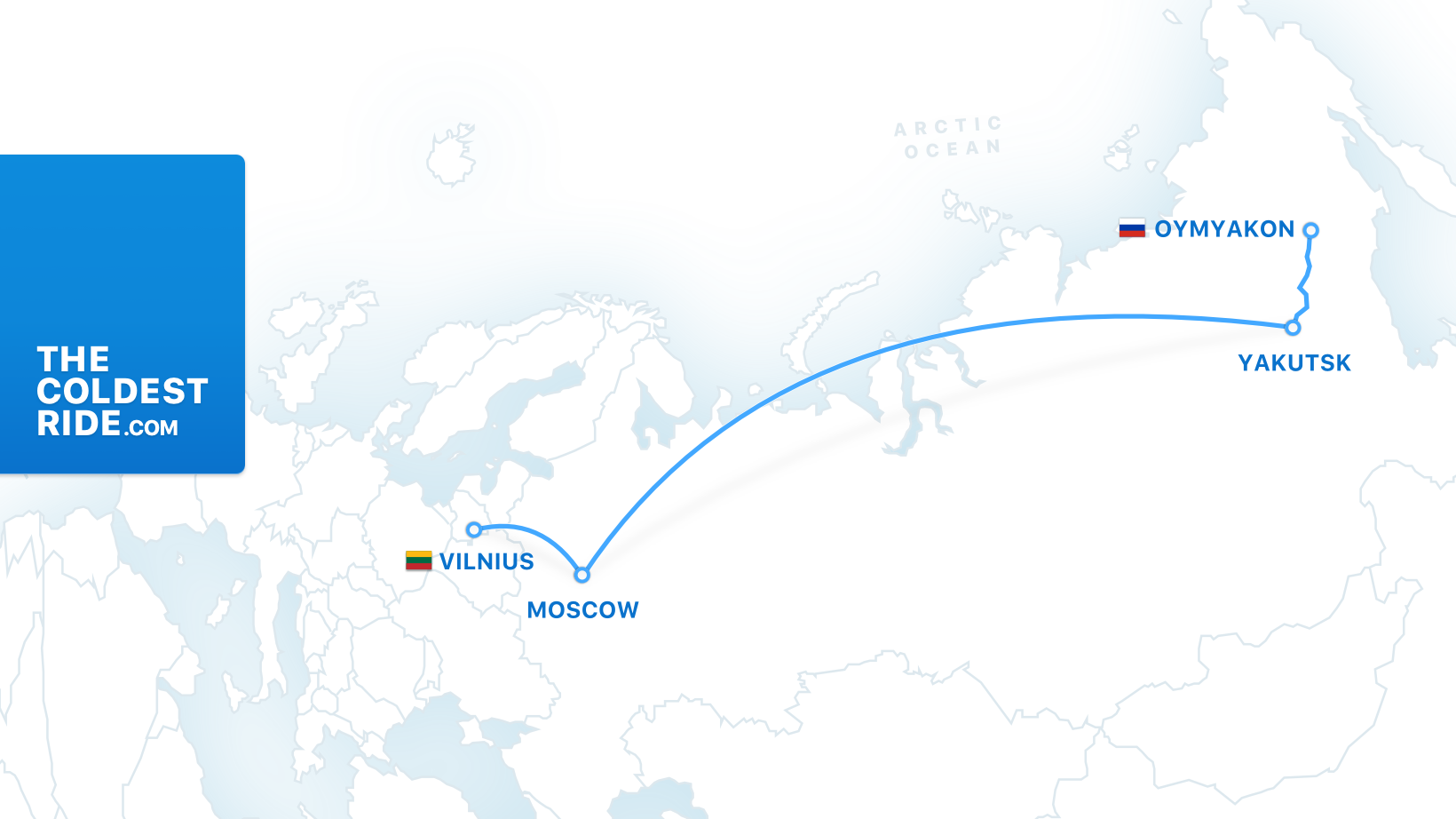

In February, Lithuanian extreme motorcyclist Karolis Mieliauskas will embark on a 1,000-km odyssey to the coldest inhabited place on Earth.

Back in the summer of 2017, Karolis Mieliauskas rode his single-cylinder Yamaha motorbike across frozen Lake Baikal, the deepest lake on the planet. On the seven-day, 765-kilometer journey, Mieliauskas battled snowdrifts, howling wind, massive ice fractures, and extreme cold.

This February, he will revv up his motorcycle’s engine for an ambitious 1,000-kilometer tour of Siberia’s infamous Kolyma Highway, dubbed the ‘Road of Bones’ due to its dark history. Mieliauskas plans to traverse a section of the treacherous artery from Yakutsk, capital city of Russia’s Sakha Republic, to Oymyakon, one of the coldest continually inhabited places on Earth.

The ‘Road of Bones’ is no joyride.

Something about the emptiness of Siberia enchants the 36-year-old Lithuanian. He got the itch to ride north a year and a half ago and couldn’t shake it, “though I tried to avoid the thought for a long time,” he admits. “Who wants to go to the coldest place on earth?!” Mieliauskas likens his attraction to the Road of Bones to a mountaineer’s preoccupation with summiting Everest. Navigating the unpaved, remote Kolyma Highway just might be the motorcyclist’s equivalent of summiting the world’s tallest mountain.

The desolation, tempestuous wind, and extreme cold temperatures of the route deter most travelers; the ‘Road of Bones’ is no joyride. But in the cold and solitude, at the helm of his Yamaha, Mieliauskas finds space to meditate. “I’m a researcher of the mind,” he asserts. “I am interested in exploring the signals our brain produces in extreme situations.” His approach to mental fortitude is nothing short of superhuman. As a sort of training regimen, Mieliauskas spontaneously plunges into ice-cold lakes and streams. “Sometimes, when I am walking my dog in the middle of winter, I pass a lake, and suddenly my brain wants to jump in the freezing water,” he describes. “In that moment, my mind goes very crazy. I get signals not to do it, but when my head is underwater, there is silence. It’s the silence of truth. I’m in the water, I’m not dead—and I get out—I’m cold, but I’m alright.” In meeting the polar-plunge head-on, Mieliauskas conditions himself to tolerate freezing temperatures. “This is how I like to play with my mind—to explore the internal human,” he says.

-60℃ (-72℉).

Mieliauskas’s preternatural mental fortitude is vital in a land where the thermometer dips to -60℃ (-72℉). In winter, district officials warn motorists to keep their engines running to prevent stalls. At such temperatures, mettle—and metal—can abruptly snap. Mieliauskas has the resolve to weather the Siberian winter, but is his titanium and carbon-fibre motorbike prepared for the journey? “We made preparations for technical aspects,” he says. “We had to make some modifications for the cold including aviation-grade bearings, special oil for the engine, and studded tires to avoid slipping.” His engine is bedecked with custom covers and insulation to trap heat. It’s a robust outfitting, but in the biting cold of northern Siberia, smooth sailing is far from guaranteed. “There are hundreds of question marks, but we’ll just have to see what happens on the road!” Mieliauskas laughs.

The Yamaha’s wheels will skitter over a causeway gouged through the permafrost by prisoners of Stalin’s gulags. Directed by Soviet mineral desire and armed with pickaxes and wheelbarrows, forced laborers scoured the frozen landscape for gold in the 40s and 50s. The Kolyma Highway emerged incrementally as a solitary, haphazard conduit to the gold panning sites. Abandoned gravel pits, scrap heaps, and work camps pockmark the tundra alongside modern-day dredgers; most locals still depend on mineral extraction for livelihood. Soviet-era prospectors died by the thousands under inhumane conditions in the gulags and exposure to the elements. Their bones littered the informal highway, lending the road its chilling nickname and the region a legacy of both human and climatological extremism.

Mieliauskas recognizes his route’s regrettable history, but wants to explore the territory with a positive lens. He is inspired by the locals, who live in “a symbiosis with the harsh natural environment”. According to him, one night of the trip will be spent in a settlement of reindeer herders who have maintained a traditional semi-nomadic lifestyle for generations. Additionally, Mieliauskas enthuses, the territory is renowned for its abundance of exquisitely-preserved woolly mammoth remains. The capital city, Yakutsk, boasts a Mammoth Museum of fossils and facts on the extinct mammal. Aisen Nikolaev, the acting head of Sakha Republic, has even divulged plans to resuscitate the prehistoric pachyderm with genetic cloning.

The 'Road of Bones' is littered with peril and possibility, and Mieliauskas's "come-what-may" mentality will be pushed to the limit in the punishing elements of northern Siberia. But the motorcyclist isn't too concerned—in his own words, "Consciousness has no limits, no boundaries. To be honest, I'm more curious than afraid."

Follow his journey on social media, via YouTube, Instagram and Facebook.

https://www.facebook.com/thecoldestride

Comments ()