This article, like nearly all our writing, is a labor of love and passion. While we've made this piece freely available to all readers, joining The Outdoor Journal family and becoming a paid subscriber is what allows us to keep producing this sort of authentic, human reporting. Sign up for a paid subscription today to support our work. Together, we can keep outdoor storytelling alive.

—Apoorva "AP" Prasad, founder, editor-in-chief

Each time we arrive in the mountains, it feels like anxious motors are whirring to a stop. I slow down, leaving behind Bangalore’s chaotic hustle, traffic and polluted skies. Prayer flags greet us against a cartoon-blue sky, and my lungs expand to their full potential. By the time we reached Rakchham, however, late at night, the stars said hello instead, in a great expanse of pitch black sky.

It would take me the same amount of time–or maybe less—to reach Boulder, New York or Oslo, from Bangalore.

That’s just how big and disconnected India is, a realization that strikes in a visceral way when travelling across the nation.

From Bangalore in southern India, it’s a 3.5 hour flight to Chandigarh in northern India, the last major city with an airport before the Himalayas. Then, a 5-hour winding bus ride up into the Himalayan foothills, to Shimla, the regional capital of India’s northern state of Himachal Pradesh.

And then, a 10 to 12-hour taxi ride through never-ending valleys with massive drops down to fast-rushing rivers, the terrain becoming ever steeper and rugged, before taking a turn up into the almost hidden side valley of Sangla on a road that seems to go to the end of the world. The border of Tibet is practically a stone's throw away.

Bangalore is an urban dome, sloshing in tech innovation, startup culture and apocalyptic traffic jams. Estimated human population: 14.4 million.

Approximately 2049 km (1273 miles) north as the crow flies, Rakchham greets you with pristine air, huge mountain massifs, buckwheat fields and orange specks of wild seabuckthorn. Population: 754.

In Hamskad, the local dialect, Rakchham means ‘rock bridge’. The valley certainly justifies its name. Located in the Kinnaur district of Himachal Pradesh, at an altitude of 10,000 feet (3,048m), Rakchham is a village that sits among sprawling Himalayan peaks upwards of 20,000 feet tall, with the Baspa river flowing below. Village homes are strewn between building-sized boulders. The landscape feels… intense.

For non-climbers, Rakchham’s boulders could be geological decorations. For us climbers, however, they become tapestries that shape the most personal experiences. Yes, it seems silly. Stumble upon a boulder, attempt to climb it, name it, assign a difficulty level, and let this grow into an experience that generations could share.

Such tapestries exist in many climbing areas across the world; Dreamtime in Cresciano, Switzerland; La Marie-Rose in Fontainebleau, France; Midnight Lighting in Yosemite, USA, or Floatin’ in Mizugaki Yama, Japan.

The Rakchham Bouldering Festival was a formal unveiling of the area as a climbing destination. Central to the event was the launch of a guidebook that was fifteen years in the making. My friend, climbing legend Bernd Zangerl has authored and self-published the guidebook. Bernd is an Austrian climber who I first met in 2018 while climbing in Rakchham.

To those even remotely close to climbing's orbit, he's considered a visionary (but more on Bernd's resume later). At a single glance, it’s incredibly evident how personal the project has been.

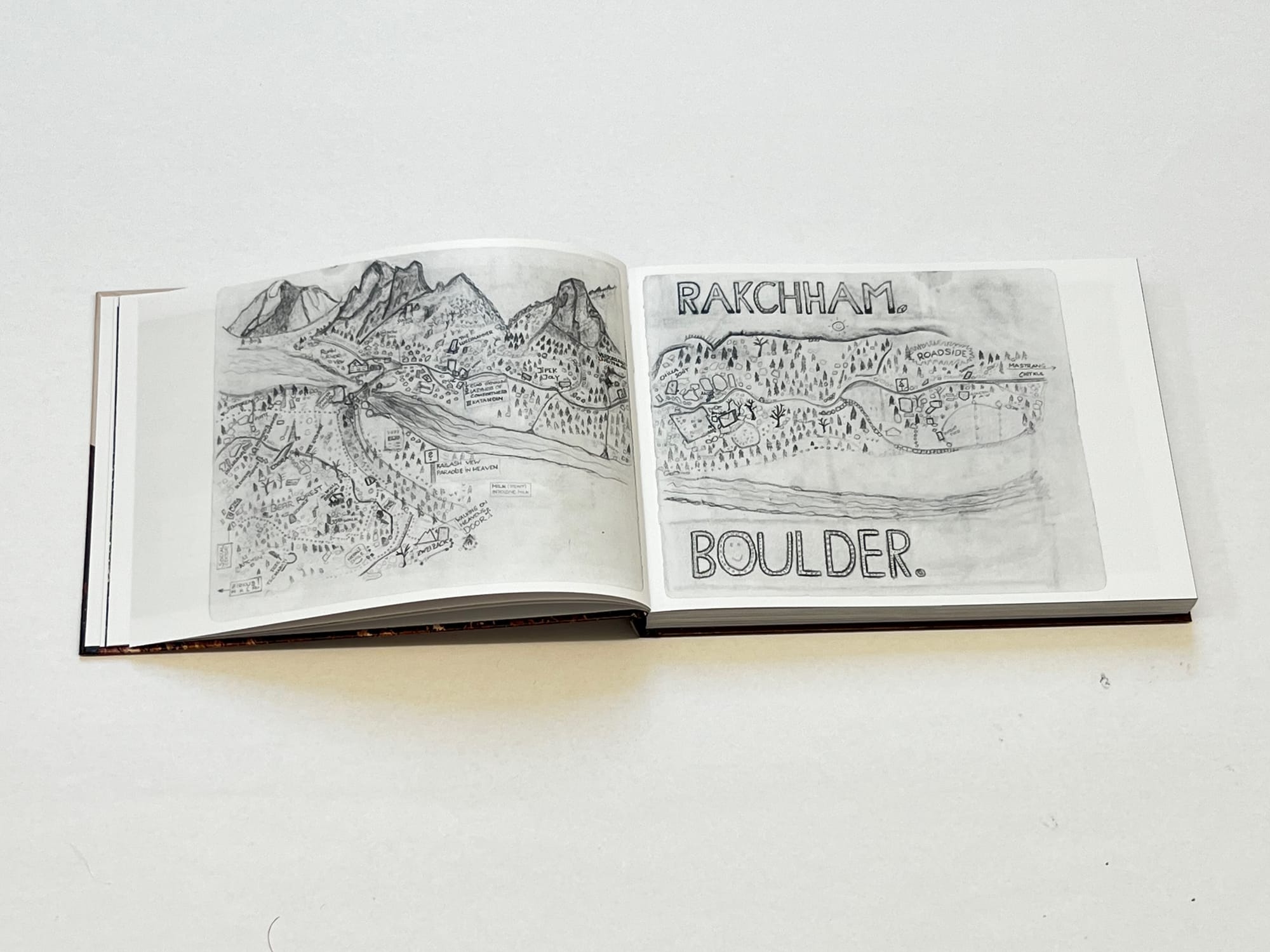

Bouldering areas are typically divided into smaller sectors and then subdivided into clusters. ‘Rakchham’ lists 560 problems across 14 sectors. The topographic maps and overviews are all hand-drawn.

While modern guidebooks lean towards GPS tagging and digitized maps, Bernd’s guidebook has a far more human touch – one conducive to connecting you with the area, as opposed to just presenting consumable ‘challenges’.

But the festival was about more than just climbing. For instance, there was a bird watching workshop conducted by Santosh Kumar Thakur, Block Forest Officer, Rakchham (Kinnaur) and Mahesh Ronseru, an environmentalist, wildlife photographer and social activist from Kinnaur. The Rakchham-Chitkul Wildlife Sanctuary, a protected reserve which adjoins the village, is spread over an area of nearly 31 square kilometers (12 sq mi). The elevation ranges from 10,000 to 18,000 feet.

This is one of the most biodiverse regions in the Western Himalayas. The avifauna is diverse and incredible: Himalayan griffon vultures, golden eagles, Eurasian wrynecks, common kestrels, snow pigeons and if you’re lucky, the elusive long-legged buzzard.

Climbing areas with this sort of thriving wildlife are rare. Across Europe, climbing destinations have been overtaken by human activity and historically, hunting. Now, they sit as nature’s versions of ghost towns.

One morning, as I was eating porridge, a griffon vulture flew within two feet of my bowl. The regal scavenger of Himalayan skies, with a wingspan of nearly 10 feet. Across India, vulture populations have been notoriously decimated due to Diclofenac poisoning. Here, they thrive and feed freely.

Another time, I spotted the relatively rare Himalayan weasel, trotting across to a buckwheat patch next to the village. After a long climbing day, a pair of Himalayan pine martens on a birch tree. Nearly every other day, scat of some kind, and pugmarks of the Himalayan red fox.

It's a genuine relief to share a natural space that feels so alive, not with humans, but other denizens of this planet.

However, it’s sometimes hard for (some) climbers to accept that these are shared spaces. Bernd wanted to address that attitude with his efforts in Rakchham.

Let me elaborate: Imagine you find a 25-foot boulder, with a potentially great line. However, there’s a tree stump, which makes the landing slightly unsafe. Do you choose not to climb the line, or cut the stump to make it safer?

In many parts of the world, the stump would be cut and logs would be used to build a safe landing. Eventually, the boulder and area itself simply becomes an outdoor climbing gym. In some places, Bluetooth speakers are brought out, music is blasted, cigarette butts are left behind and climbers become nature’s new colonizers.

This was a scenario Bernd had witnessed in Switzerland, and was eager to avoid.

Magic Woods, a small natural forest near Ausserferrara jammed with granite boulders, is one of the most famous bouldering areas in the world today.

But for many years, before it became famous, it was Bernd’s ‘living room’. A quiet backyard that only few people knew about. With a small group of friends, he established many of the area’s hard classics.

In 2002, when word got out about New Base Line, which Bernd had graded 8C (at the time, the hardest bouldering grade in the world), the area blew up. Climbers from all over the world descended upon this granite paradise. Magic Woods was suddenly the hottest new destination.

This seemingly inevitable surge came with its complications. Vegetation was destroyed from pads being thrown over. Holds got over chalked and lost texture. There were conflicts with local landowners. Fueling this was an overexposure in climbing media – articles, films, social media, brand campaigns.

Naturally, Bernd felt culpable. So what would happen when he chanced on a climbing paradise all over again? A mix of excitement, tinted with guilt. The proposition of nearly infinite climbing potential, temperate weather and a remote, mystical setting is something any explorer would dream of – a ‘Shangri La’ of climbing, imagined from an atmospheric adventure novel.

Right on its tail is the burden of responsibility. A previous ‘Shangri La’ was overdeveloped and overused, despite the developers' best intentions; how does one ensure this new utopia doesn’t go the same way?

From a climbing standpoint, Bernd had the freedom to develop an area from scratch, but THIS time, he had to ensure bouldering would exist in harmony with the land, locals and ecosystem. He couldn’t let it become a self-aggrandizing ‘outdoor’ pursuit which overtakes all else.

Surely, the first step would be to ask the locals how they feel about climbing? These conversations began with Nand Kishore (Johnny) Negi, on whose property the Rupin River View hotel was being run. Johnny became Bernd’s good friend, window to the local viewpoint and over time, partner-in-vision.

Bernd shared some of his thoughts with Johnny, and Johnny shared concerns held by the villagers. There emerged an intangible understanding.

Like Bernd, Johny was a mountain man. One was Tyrolean, the other Himalayan. The people of Rakchham felt there were some things he just ‘got’. Agricultural cycles, the ways of the forests, using fixed trails, the sacred bond between people and their natural surroundings.

On the basis of this mutual understanding, the RMAC (Rakchham Mountaineering and Adventure Club) was formed. The RMAC is a locally-run body that regulates access to Rakchham – similar to a locally-managed forest department for national parks.

In order to ensure a meaningful cycle of paying it forward, a tiered-pricing permit fee would be charged, for both Indians and foreigners. The proceeds from the permit fees would go towards trail maintenance, rental infrastructure and very importantly, the outdoor education of locals, with the objective of setting them up for careers in adventure sport.

Why tiered pricing? A different fee for foreigners and a different (usually lower) one for locals is contentious across tourism. In our new utopia, where all passports and currencies are equal, dual pricing would be unfair!

But, this still isn’t that world, is it?

Earlier this year, I wanted to visit my sister, who (legally) lives and works in Germany – she's a Principal Product Manager for Spotify. Some background: unlike citizens of many developed countries, Indians need a "Schengen Tourist Visa" just to visit Europe (and similar visas for most of the world).

These visas aren't easy to obtain, are relatively expensive, and require an incredibly large burden of proof. That is, proof of innocence, of non-(illegal) immigrant intent. That's right, we can't just go take a gap year to backpack across Europe, or go bouldering in France, or skiing in the Alps. It's literally (almost) impossible, thanks to a nearly insurmountable barrier put up by European governments.

My sister sent across an invitation letter, with additional documents showing her income and employment in Germany. I gave the German Embassy proof of my property ownership in India, along with tax returns and every other form of documentation. My partner shared proof of property ownership, a business and other details.

After many months, we were called for an interview. We were taken into a separate room, then asked to spread our hands and recite our date of birth, place of birth while being recorded. All this, to simply visit a family member who's already in the top 5% of taxpayers in Germany.

This official Germany / EU visa process felt humiliating, infuriating, and unnecessarily discriminatory, clearly designed to make Indians feel inferior to Europeans (or those with stronger passports). But this was the only way for me to visit my sister (or go climbing in any of the earlier European hotspots I just mentioned).

Three weeks later, I got a rejection letter vaguely stating that there was ‘suspicion around my intent to return’. So did my partner.

We weren't allowed to go to Europe.

When I shared this anecdote with a few Danish climbers in Rakchham, they were rightfully shocked. And apologetic.

I bring this experience up simply to point out that considering the position of disadvantage my compatriots have in the rest of the world, it really isn't a big deal to have a separate permit fee for non-Indians (or similarly tiered systems in tourism elsewhere). Merely an acknowledgement of geopolitics, and a rightful ask to contribute according to ability. I mention this in detail because it’s the kind of experience that often gets tucked away into emotionless boxes of "bureaucracy" or "procedure" while ignoring the socio-cultural and human cost of the process. And because most Europeans are simply unaware of how it all works for the rest of us.

I also think it's necessary to understand why the RMAC believes foreigners should pay a higher permit fee.

As Bernd additionally clarified, "the €100 fee for non-Indians is something we (Europeans) voluntarily came up with, because we felt we could afford it. For students and others, it's lower".

This position of disadvantage has also kept Indian athletes lagging behind the global cutting edge for decades. Travel to more well-established areas – for example; Fontainebleau in France, Bishop in the United States, Rocklands in South Africa, Magic Woods in Switzerland – remains an outrageously expensive and often logistically impossible proposition. Within India, there were too few gyms, with the infrastructure that was (and often still is) decades old.

In recent years, a serious hunger, born of that disadvantage, may have created an equalizer. It reminds me of Jamaica’s takeover of sprinting in the mid 2000s; a time when it was considered impossible to become world class until you moved and trained in the United States. However, Asafa Powell chose to stay and train in Jamaica, despite its limited resources. That decision kickstarted one of the most dominant runs in any sport’s history. Usain Bolt, Shelly Ann Fraser Pryce, Elaine Thompson Herah, Yohan Blake and many more came out of that homegrown wave.

“..and most importantly, many of the strongest climbers in India are here! And they are fucking impressive!” Bernd gushed during the presentation of his guidebook. It was a matter of genuine pride that India is now producing climbers capable of repeating and establishing climbs of more elite grades.

One of those incredibly promising prospects is a kind-mannered, empathetic young kid, born into adventure, exploration and climbing. His name is Arlo, and he’s my son. He just turned eleven. Normally, I'm not comfortable speaking about him or our personal life, especially in praiseworthy terms. It was my editor, AP, who eased that barrier... suggesting that it's hardly narcissistic, but honest and authentic to write from this perspective. A great editor is one who can gently shift the needle, while maintaining the integrity of ideas. AP is a fantastic one; he made me feel... OKAY to write about Arlo. I thought it essential to mention this.

One of the components of the festival that made the greatest impact on him was the barefoot climbing workshop by the French climber, Charles Albert.

Charles is one of the greatest boulderers in the world. But he’s more of an artist than athlete. Charles is known for not using climbing shoes, and yet accomplishing some of the hardest movements that humans have been capable of. In a sporting ecosystem that’s always selling you the latest innovation in footwear, chalk, clothing or training gear, Charles is uniquely under-engineering elite performance. Imagine showing up at the Olympic 100m finals, without running spikes; that would be the equivalent of Charles!

Arlo describes his style of movement as 'living slime'.

Charles Albert on Extra Long, Extra Strong (8B+), Arlo on Beeing Crazy (7B+), Climbers from over 14 countries gathering for a bonfire, during the festival, Bernd being felicitated by the locals, Two locals from Rakchham, The Kinnaur Kailash massif bathed in golden evening sun, Kehihyulo Khing on Ciao Giovanni (8A), Bernd's hands-free slab challenge during the festival. CREDIT: Ray Demski and Kalpa Bhuyan

The absence of climbing shoes produces a far more intuitive manner of movement that’s very harmonious to watch. It doesn’t feel practiced or too ‘clean’, as some elite climbers appear.

Throughout our season in Rakchham, Arlo would alternate between climbing shoes and bare feet, depending on the moves. It was incredible to watch how he ‘tinkered’ with climbing, instead of reducing it to crystallized objectives.

That experimentation informed his ascent of Bernd’s classic, Premium Gravity, graded 8A. For morphological reasons, the sequence used by adults didn’t work for him. Instead, he invented a completely different sequence to unlock the crux (the most difficult part of a boulder problem).

Much of this revolved around a hold that felt glassy in texture, when the wind is still, and usable for a very brief period of time.

He actually described this situation to his school (it’s a digital project-based learning collective called Stay Qrious), and they were incredibly supportive of him playing the weather to his advantage. While from an athletic and historic standpoint, the ascent was obviously impressive, what made me the happiest was his playful focus. Learning how to detach from the outcome and simply show up to play is an advanced state of mind, which even I struggle with. Throughout his process with Premium Gravity, Arlo put on a masterclass for me.

A recurring theme in our conversations is curiosity. While walking past boulders, we often talk about looking for features, as opposed to chalk marks. Rakchham is that place which rewards the curious. Of course, the guidebook has enough for a climber to ‘go through’, but to really enjoy the valley’s potential, I’d argue that it’s essential to have a roving eye–to wonder about what could be in this cluster, and that, and that one even higher.

Bernd often laments the extreme gamification of bouldering in Europe. Even before arriving in an area, people have watched hundreds of videos, know the texture and orientation of every hold on a problem, and likely trained on replicated models in their gyms. Where’s the mystery and the novelty? That very life force of climbing, and adventure itself?

With Rakchham, he hopes to attract a breed of climber that seeks freshness. While leaving, we stopped for breakfast in Kharogla, a village about ten minutes from Rakchham. After ordering chai and aloo paranthas (potato stuffed flatbread, a common breakfast in North India), Arlo and I decided to wander through a chaos of boulders right below the dhaba. The autumn sun was tenderly inviting, and the boulders mostly had flat, grassy landings. We wandered through dry apple trees and golden brown grass, getting lost in a remarkable maze of granite angles.

"Just that next one, and we turn back?" I’d ask, cautious about having gone too far from our dhaba.

Many ‘next ones’ later, I was still talking about the flat landings and idyllic setting. "Like the Rocklands, but maybe we should call this sector The Flatlands," I said.

"Maybe we should call it Flatlandia," Arlo responded.

With additional input from Bernd Zangerl and Johnny Negi. Edited by Apoorva "AP" Prasad.