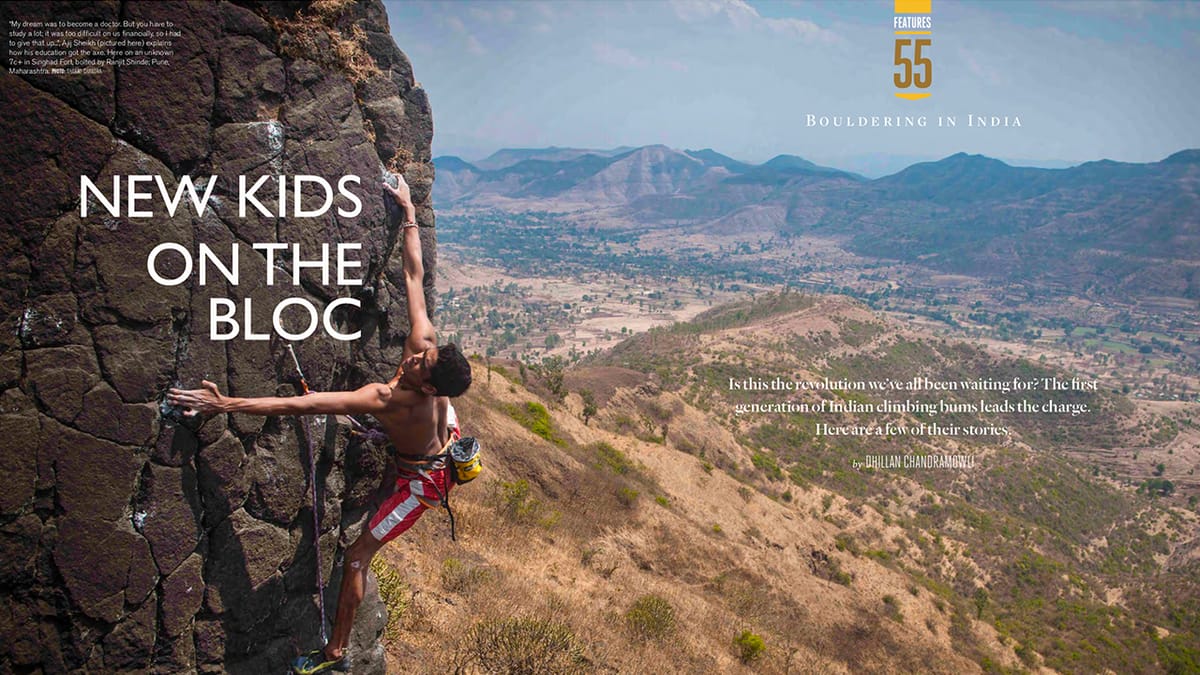

New Kids on the Bloc: Boulderers in India

Is this the bouldering revolution we’ve all been waiting for? The first generation of Indian climbing bums leads the charge. Here are a few of their stories.

This story was originally published in print, in the Summer 2014 issue of The Outdoor Journal, you can subscribe here.

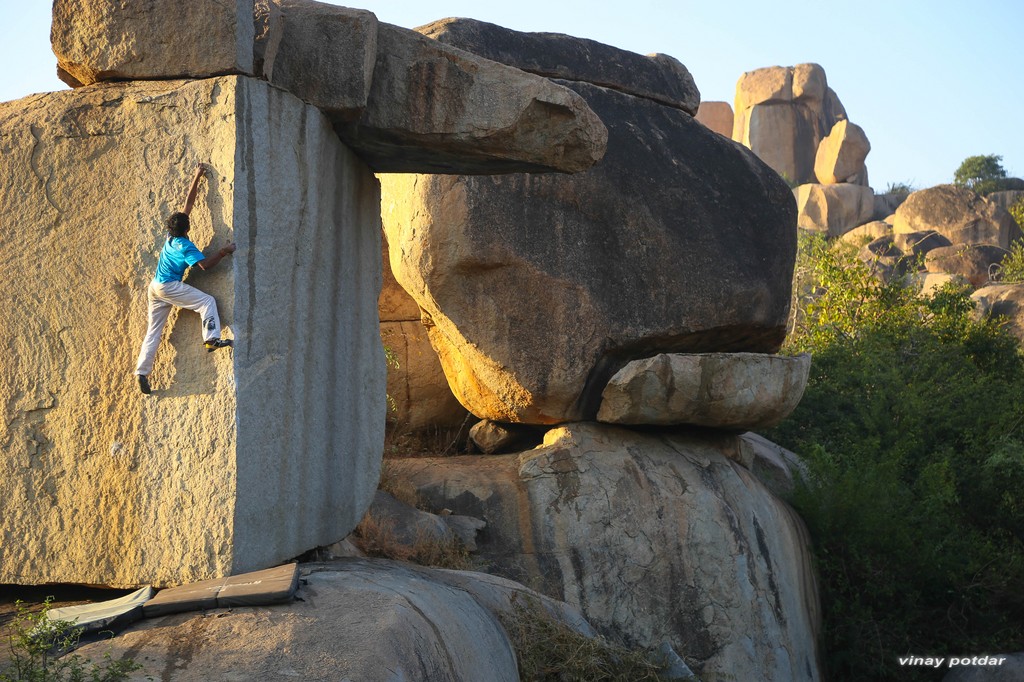

It was a mildly overcast evening on December 15th, 2013. A pleasant breeze blew across the ancient granite formations of India’s bouldering mecca, Hampi – perfect conditions to attempt The Diamond, a superb 8a sloper arête.

Indian climbers were pushing harder grades than the normally dominant European visitors.

Ajij Shaikh, a stick-thin, withdrawn young man was alone nearby, composing himself. He’d come excruciatingly close to completing it, but had repeatedly failed at the crux. He stood up to return to the problem. Taking off his shirt, he revealed shred upon shred of lean brown muscle. Ajij pulled on a pair of borrowed climbing shoes, took a few breaths and sat down to try again. I stood behind, ready to spot him should he fall.

This time he flowed through the traverse. A slightly different heel-hook and mantle pushed him through the crux. When Ajij topped out, he became the first Indian to send an 8a graded boulder problem. Within the next two months, Sandeep Kumar Maity and Vikas ‘Jerry’ Kumar would follow with more 8a sends.

The 2013-14 climbing season in Hampi, of which I was a part, was the first one ever where Indian climbers were pushing harder grades than the normally dominant European visitors. Here in India, with an extremely nascent mainstream climbing culture, this heralds the emergence of our first generation of climbing bums – individuals willing to forsake everything for the sole purpose of climbing hard and exploring their potential.

But where did this begin?

He comes back into town either for rations or to watch a cricket match

My starting point was Paul ‘Pil’ Lockey, a forty-five year old British juggler and climber from a trad background who’s established the largest volume of bouldering in two of India’s biggest areas – Hampi and Himachal Pradesh. Normally ‘Pillu’, as he’s known by Hampi’s locals, stays in caves while developing bouldering areas. He comes back into town either for rations or to watch a cricket match. Our conversations would happen during those windows.

“I was looking down...and there was this wolf, just standing there!” he laughed, while telling me about his experience after topping out one of Hampi’s most revered problems, Kundalini Rising. “It’s so hard to find a new three-star 7a problem in England...but here in India, there’s so much potential.” His Indian obsession began with a postcard of Hampi he received in 1992, from Jerry Moffat, Kurt Albert, Johnny Dawes and Bob Pritchard who were exploring its potential at the time. “It was just boulders...for miles...I couldn’t pass on this” he laughs, recalling how near-ridiculous Hampi’s unexplored potential seemed to him then.

In 1993, he visited for the first time with his then girlfriend. The first problem he opened was Cosmic Crimp (6b+), a near-30-foot highball. “I had to on-sight it, and there were no crashpads at the time” he recalls, explaining how bouldering developed into a real and separate discipline in climbing only in the late 90s. Since ‘93 he’s visited every year, staying months at a time.

“Did you come across any Indian climbers in Hampi, back in the 90s?” I asked Pil. “A few...mostly from Bangalore...but it wasn’t too crowded until 2004” he said, referring to the climbing tourism boom Hampi experienced after the release of Pilgrimage, a movie documenting Chris Sharma’s climbs in the area. Yet somehow Himachal’s star visits didn’t have quite the same effect. Fred Nicole and Bernd Zangerl, two of the most pivotal figures in bouldering history, visited and established classics such as “Nicole’s Problem”, a 7c+ overhanging arête in Solang, which I was working recently. This lack of interest perplexes Pil, who feels Himachal is superior to Hampi. “I first came there in 2002, from the Rocklands (South Africa), looking for something to climb during the summer...” he recalls. With other travelling climbers, Pil and Harry developed bouldering in Manali, Chhatru, Chota Dara and the boulder fields between Lahaul and Spiti.

Where were the Indians then? I turned to Mohit “Mo” Oberoi for answers. A veteran climber from Delhi and the founder of Adventure 18, one of the first outdoor gear stores in the country, Mo “was hanging around the crags of Delhi – Dhauj, DamDama, Old Rocks and PBG.” When he came down south in 1986 to climb Savandurga (a 1200-foot high monolith showcased in The Outdoor Journal Issue 01) he met Dinesh Kaigonhalli, another figure well known in Bangalore’s circles. Along with many other now-forgotten names, they put up big wall and sport routes across the country.

And Mo wasn’t at today’s warm up levels either - back in 1994, he was climbing E7 (7c+) trad routes. Neither was Indian bouldering stagnant - by the early 2000’s, areas like Turuhalli near Bangalore had plenty of classics, put up Indians who’re mostly in their 40s now. So what happened then? Why hasn’t anyone else heard of them, and why has the Indian climbing growth curve been so slow?

“Rocks, rocks, rocks!” yells Mo, who represents the old guard of English-speaking, public school educated climbing enthusiasts. He says that the younger generation of climbers got too wrapped up in competition climbing, spending little to no time on natural rock. Since my generation is finally working on outdoor projects again, grade progression is finally visible, he says.

But why was this generation ignoring natural rock in favour of competitions?

It’s the economy, stupid.

Mo’s generation and the Himalayan Club lot came from a wildly different socio-economic strata than the post 90’s climbers. The later young guns came from socially conservative, poor backgrounds, unlike their predecessors. Their families often expected and required financial support from their children. Competitive climbing did not require the resources that outdoor climbing did, while offering the promise of returns via cash prizes of up to Rs. 20,000. It simply became the more viable option for those with climbing skills. As for the other upper-class kids from the 90s? Well, they just left the country to live and climb abroad.

I’m fairly sure climbing came to mean different things to the two generations - high slinging, adventurous pursuit to one, and escapism from grim class realities for the other. This is also reflected in this new generation’s interest in bouldering, literally the freest form of climbing - vs. expensive “trad” and alpine climbing.

India is the world’s third largest economy today, by purchasing power parity

Finally, the nail in the coffin was a total lack of climbing gear, media, support or indoor infrastructure. India doesn’t have the kind of gyms available across Europe and North America. When I started climbing, about four years ago, we were practicing bouldering on the lower panels of a lead wall. Campus boards, fingerboards, sling trainers and the general equipment and knowledge used for performance training aren’t largely available even today. But why?

Sponsor me, please?

India is the world’s third largest economy today, by purchasing power parity. It’s a huge potential market for big outdoor gear companies… or isn’t it? While writing this article I emailed several outdoor brands in the US and Europe. Many just didn’t reply. Brooke Sandahl, VP of Metolius, did. “We sponsor a number of athletes who gain exposure for us. Many athletes are sponsored with our distributors on a country-by-country basis. In North America, we are partnering with many non-profit organizations that promote climbing” he said, explaining how they support the climbing community. The problem, it appeared, was that international brands wanted to work with distributors in India, and local distributors weren’t (and still aren’t) willing to risk investing in a nascent sport or culture; and the little they do is a miniscule drop in the ocean.

So, why hasn’t there been any active interest in organizing big events like the Petzl Roc Trip or Kalymnos Climbing Festival? Such events bring a lot of attention to the sport, which is often a first step. “Many of our alpine athletes come to climb incredible peaks. India isn’t well known for other styles of climbing. Hampi for bouldering, I have seen some amazing sport climbing there but a country needs to be proactive if they want this type of event.”

While my peers are crushing hard, they’re still to learn how to use their achievements to promote themselves and the scene. Brooke explains how that’s crucial to obtain sponsorship through Metolius. “Currently, the level needed is mid 5.14 (8c/8c+) for rock and V12 (8a+) for boulder. People who don’t climb super hard but open lots of quality routes, help with national, regional or local access issues, coach a climbing team, write a well-read blog, gets his/her photo in the magazines (thus our products), take lots of good images or make films...can all enjoy some level of sponsorship...from a tee-shirt, to paying an athlete cash and everything in between!”

That covers at least eight Indian climbers immediately. Bar one, Tuhin Satarkar (Red Bull), none of them are supported by any international brand. Here are three:

Sandeep Kumar Maity:

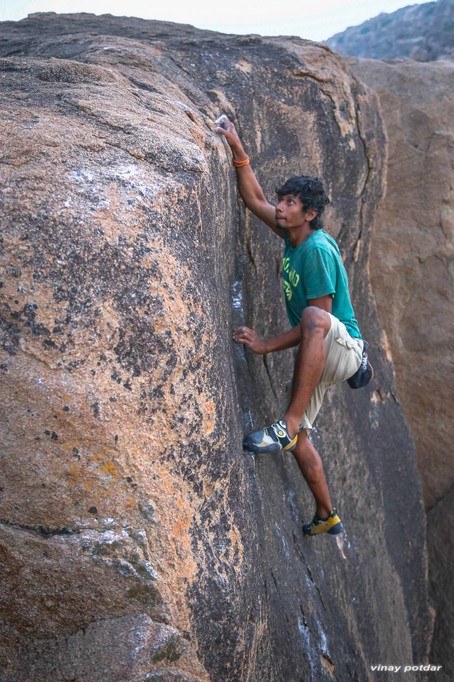

After nearly thirty unsuccessful attempts on Ayurveda (7c+), a crimp-to-crimp power sucker at Hampi, Sandeep seemed spent. He put on his shoes for a token ‘last try’, took an impatient breath and went for the take off. He grimaced through every move and finally stuck the last dyno with a violent right leg swing propelling him. When it was done, even he couldn’t figure out where that extra juice had come from. But Sandeep is no stranger to running on empty.

Sandeep was introduced to climbing in 2006 by his sports teacher, Mitra Ghosh, at his school in Delhi. His father was a supervisor at an offset printing press, and his mother a housewife. Five people – his parents, his sisters and him – share a small one-room house. Like many from that section of Indian society, travel was a unattainable dream. His earlier fantasies were more in cricket than an obscure sport like ‘climbing’.

In 2008, after his 10th class Board exams, Sandeep heard about a climbing wall at the Indian Mountaineering Federation (IMF) in South Delhi. With not much else to do, he started going, carrying lunch from home and sharing a pair of Converse sneakers with three others. He speaks gratefully about the people who mentored and even supported him financially – Amit Sharma, Naveen Arya, Norbu Bhutia, Sushil Bera, Nanda Kishore and Manjeet Singh. “I still remember borrowing a pair of La Sportiva Cobras, and winning gold at the 2008 zonals” he recalls.

Sandeep’s family does try to understand his pursuit. Before heading to Manali for the climbing season, I was at his home for three days. One afternoon, I watched Dosage 5, an old climbing flick, with his father who kept bursting into “What the...” reactions of amazement. “Is there a video of you too?” he asked Sandeep, who just smiled and continued watching.

A sign of his confidence was his trip to Europe in 2012, to compete in four bouldering world cup events. He took a loan of Rs. 70,000 rupees to make that happen. The events taught him route-reading, planning and controlling nerves. But he reflects more on his interactions outside, particularly in Millau, S. France. Back home in Delhi, he pulled out a poster and proudly showed it to me – “blue skies, my friend,” signed Dave Graham. That was his full-stop moment - having Dave shake hands and introduce himself.

Vikas ‘Jerry’ Kumar:

On the day that Vikas sent The Diamond’s sit-start, four others, including me, sent the less difficult stand-start variant (7b). I had fallen off three times after nearly topping out. Vikas told me to use the edge of my palm to push off the last hold, not pinch it. “That’ll make the conversion really easy...” he said. Next attempt, I nailed it.

If Sandeep drains himself, Vikas just doesn’t care enough. He climbs hard, but it’s all play. In many ways, he’s perhaps the ‘purest’ climber of the bunch – never climbed on plastic, never ‘trained’, never competed and literally has no clue about the bureaucratic aspects of the sport.

After Vikas’ family unexpectedly lost a small business in Bangalore, they moved to Hampi. He was forced to quit school and start selling chai. Soon he met Koushik and after a few scrapes they were selling knick-knacks together. Their constant bickering got them nicknamed Tom & Jerry. Their experiment is the Tom & Jerry Climbing Shop in Viruppapur Gaddi, better known as Hampi Island. It rents out crashpads, climbing shoes, rope and other gear. The small shop runs largely on donated material and used shoes from gyms in Europe. “We make about Rs.30,000 ($500) each for the whole season. We save, travel, and then return to open for business” Vikas explains.

Like most of his Indian peers Vikas suffered the 8a mind-block. “That started opening up after I sent Goan Corner (Chris Sharma’s brilliant 7c arête problem)...” he recalls. “Initially, I didn’t think it was possible to send The Diamond; Sandeep and the others were trying it and I just tagged along...when I had a few good attempts and fell off at the last mantle, I knew it was possible.” On the cloudy evening of February 19th, we heard Vikas scream from the boulder. It had happened.

Ajij Shaikh:

Over 35 feet high and without a rope, Ajij was contemplating the next move on Mental Mantle, a hard, scary Hampi boulder problem. “Allez Shaikh...” voices encouraged him from below. He reached for a crimp, stepped up and pulled through. When he topped out the 45 foot behemoth, there was cheering with heaves of relief.

Ajij’s appearance doesn’t always reek of fortitude – stick thin and somewhat withdrawn. But once his shirt comes off for a climb, you see nothing but muscle. We first met at the 2011 national championships in Delhi – I was asked to MC the event – one year after the surprise victory that marked his arrival. Since then he’s become national lead champion three more times.

I was spotting him when he became the first Indian to send The Diamond. The only Indian World Para-Climbing Champion and our good friend, Manikandan Kumar, was capturing his attempt on video. Between tries, he’d walk off, calm himself and rehearse the final move. When it finally came together, there was a delayed elation. “Haath dikhare upar (Let’s see your hands up high!)” Manikandan had to actually ask him to celebrate. Sixteen days later on December 31st, 2013, he sent Sharma’s classic, The Middle Way. You could see the effect yoga had on his climbing – controlled breathing, tremendous body tension and absolute calm during progress.

Over the years, his own success alongside climbing flicks fuelled hope of a ‘climber’s life’ – travelling continuously, sending projects and getting featured in movies while being sponsored. “If I get a sponsor, I’d love to compete regularly on the world cup circuit” he adds. For that, Ajij has much work ahead. He admits that he lacks the knowledge and communication skills to push for sponsorship. He’s now getting offers to work as a senior climbing instructor, but he must learn the skills necessary to push his career ahead.

Looking ahead:

Healthy fights for FAs, collaborative efforts on projects and high levels of psyche to explore new areas are not exclusive to this wave. But we’re perhaps the first bunch willing to do anything to continue climbing - another career or ‘stability’ simply isn’t an option. From living in people’s shops, to living rent-free, to selling off personal belongings to stay on the road - we’ve known poverty, and we don’t care. Some compete, some don’t. This wave is simply a natural evolution on the work of our predecessors.

Maybe our efforts will lead to increased climbing tourism. Maybe this will create decent livelihoods through guiding, guesthouses, rental shops, resoling services and more. Maybe more people will climb, and maybe the (always ineffectual) Indian state departments will help. Maybe that’ll attract big outdoor brands to invest something, anything, in our climbing scene. We’re all hoping. But in the meantime, we’ll keep climbing.

Comments ()